A Father and Son Odyssey

On Coaching, Growing Up, and Getting It Wrong Before Getting It Right

South Austin

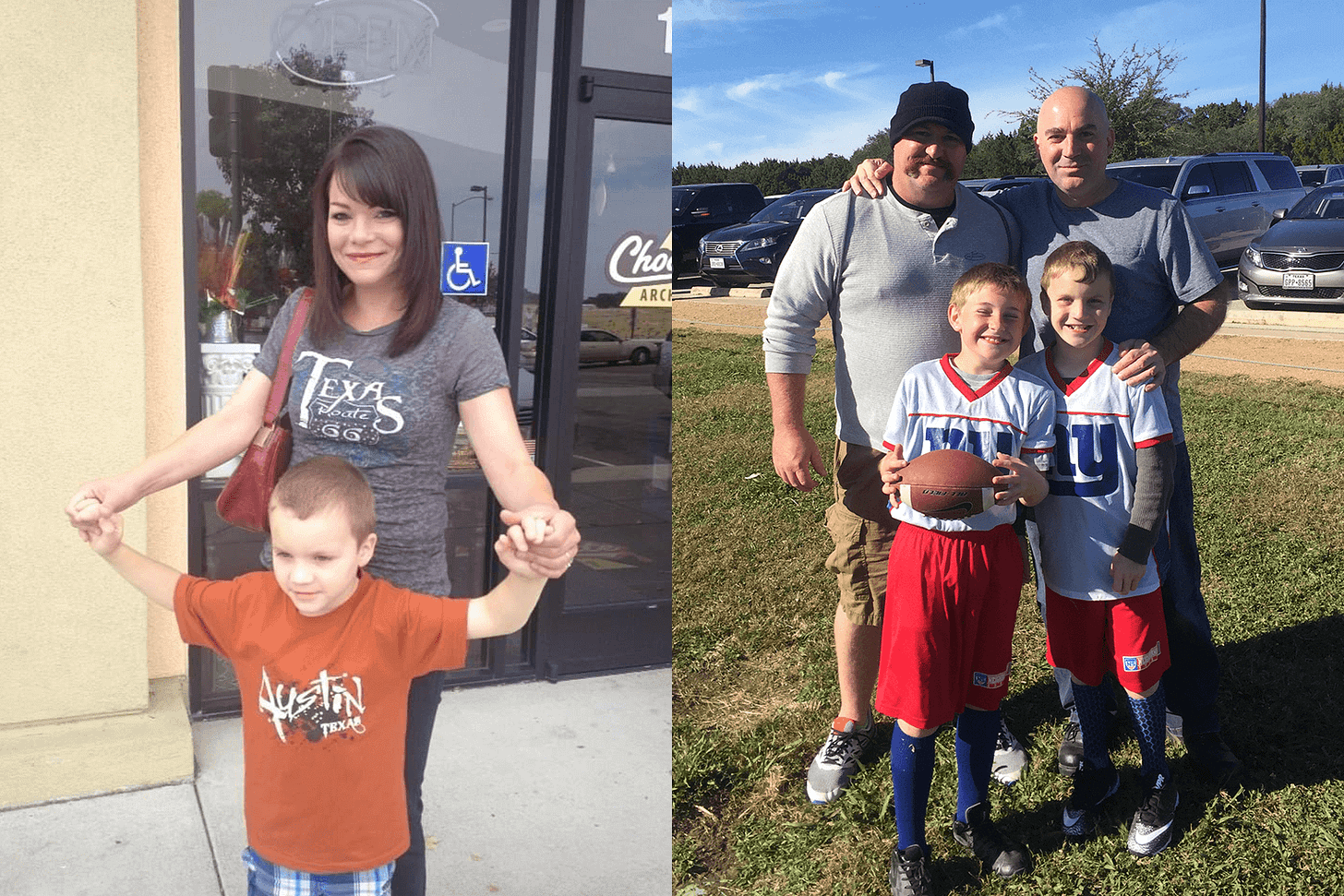

When we used to live in South Austin, my son Michael was around six or seven years old. We lived in a typical neighborhood, in a house, and I had a computer job working about twenty minutes from home. It was a pretty normal setup, the kind of life that feels settled until you realize how unprepared you are for something small.

One day, my son came up to me holding one of those small Longhorn giveaway footballs from a UT game. He said, “Look what the neighbor gave me.” I told him it was nice, and of course he immediately asked if we could throw sometime. At that point in my life, I was working a full-time job, doing SEO on the side for an air duct cleaning company, and taking on any other random computer work that came my way. I told him, “Not tonight, but for sure tomorrow after work.”

Here was the problem. I didn’t know how to throw a football. I had played some football with friends when I was younger, but I always ran the ball. I never really threw it, or at least not well. That was an uncomfortable thing to realize when your kid is standing there waiting for you to teach him something.

So I did what I always do when something I don’t know presents itself. I went straight to Google and YouTube. I spent some time watching videos and felt confident enough to pull it off, at least well enough for a six- or seven-year-old.

The next day, just as I expected, he asked if we were going to throw. I said, of course, and we went out in front of our house. I threw the ball to him, and it was kind of wobbly, but for someone who hadn’t really thrown a football much, it seemed reasonable. And really, the point wasn’t perfection. It was just spending time with him.

As we went back and forth, I started to notice a couple of things. One, I could really catch well, and he could really throw well. Two, I couldn’t throw very well, and he couldn’t catch very well. The symmetry of that didn’t escape me.

So right there, in the street in front of our house, we made a pact. I would help him catch better, and he would help me throw better. I think we even shook on it, which felt important at the time.

Around then, he started to really admire Odell Beckham Jr. with the New York Giants for his catching ability and overall athleticism. Video after video of OBJ showed up in my phone history or my wife’s. Little dude was hooked. A total Giants fan and a total Odell fan.

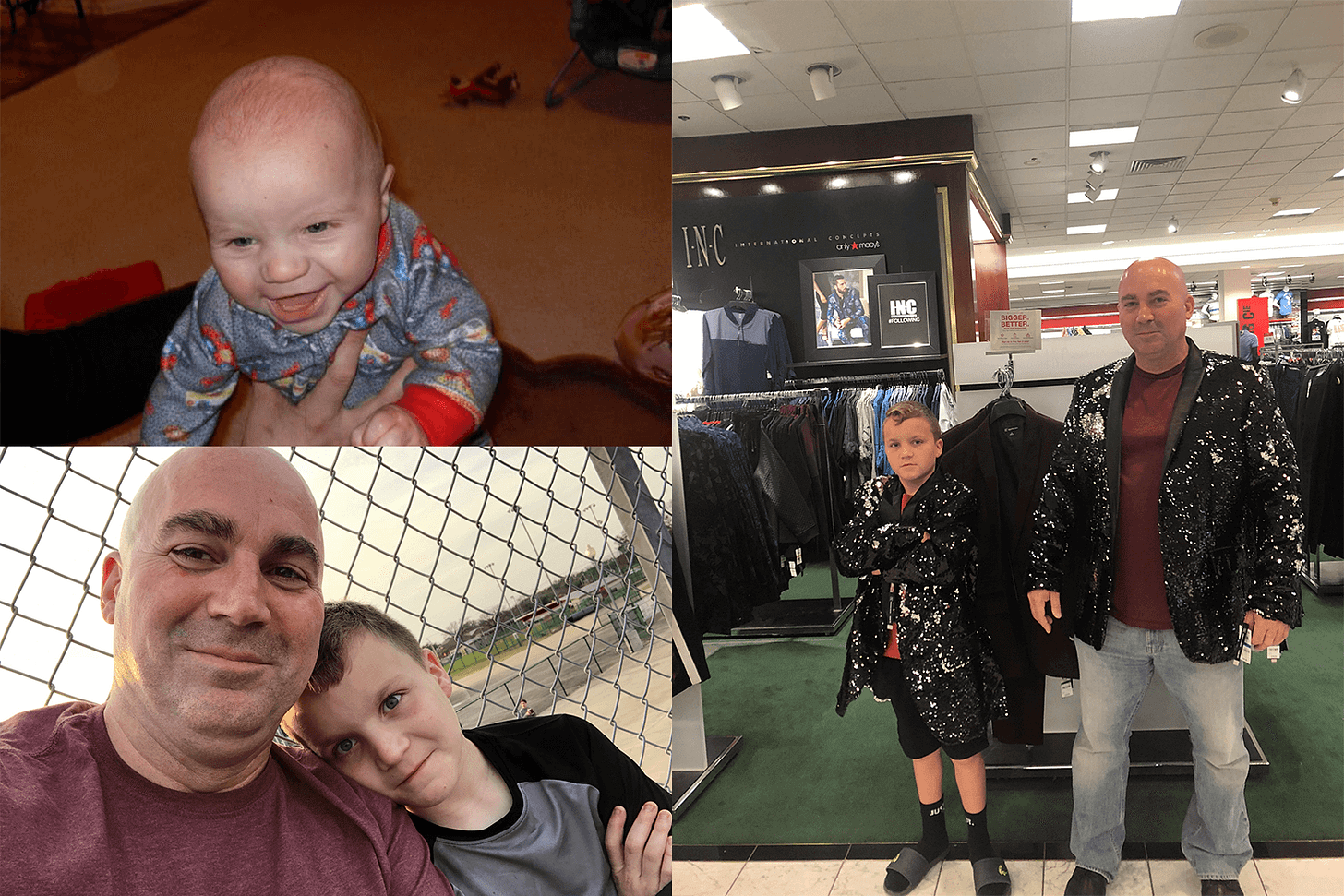

He wasn’t always the receiver that he is now. Hard to believe. lol

We threw most nights. My wife took him to the local park and they threw. He started getting the catching thing down pretty well, and for a kid, he already had a cannon for an arm. Eventually, he asked if he could join a flag football team. We were just getting ready to move toward North Austin because the company I worked for had moved further north and the commute was getting ridiculous. I told him that after we moved, we could look into it, quietly hoping he might forget.

He didn’t.

The Move North

We ended up in a suburb near North Austin, about five to ten minutes from my employer. Pretty cool. We were able to move over the Fourth of July weekend. Michael was still pretty small at this point, still only seven, and didn’t really see easily out of the back windows of the car. That turned out to be a blessing, because moving to the suburbs came with something I hadn’t expected: flag football league signup signs everywhere, on nearly every corner.

I looked at my wife and we both thought maybe he wouldn’t notice. I’m not sure why we were against it, other than it felt unfamiliar and a little weird to us.

It didn’t matter. On one of our first outings, before we even got out of the neighborhood, his head popped up and he said, “Hey, there’s a sign for a flag football league. Can I sign up?”

So, like every good parent giving an appropriately vague response, we said, “We’ll see.”

I checked out the league’s site and it seemed safe enough. I’ve always been a bit paranoid about our kids. I’m not a fan of sleepovers or school functions like summer camps. I’ve always worried about child predators and things like that. It’s just how I’m wired.

I told my son I would sign up as an assistant coach, figuring I could tag along, watch the main coach, maybe learn a little, and then, if everything looked good, fade into the background as a sideline parent rooting for his son, the future Odell Beckham Jr.

When I signed us up, it asked the usual questions and mentioned a background check, which made me feel a bit better. It also asked what my favorite football team was. We were transplants from California, and I grew up in the Bay Area as a 49ers fan. My parents loved them, so I guess I did too. But knowing how Texans sometimes feel about Californians, I put “The Dallas Cowboys” just in case it mattered, hoping they wouldn’t assign us to that team.

About a month later, I was at work checking my email when a message from the league came in. It said, “Thanks for signing up, Coach,” and included a rulebook and roster. I assumed it was a generic form email, since I wasn’t the head coach, just an assistant.

Then I opened the PDF.

There I was, listed as the coach. The only coach. A roster of ten kids, including my son.

I scrolled down a bit further and saw the team name. Thank God it wasn’t the Cowboys. It was the New York Giants.

I immediately texted my wife and said she would never believe what had just happened. The league had made me the one and only coach, which was funny because I didn’t know much about coaching and wasn’t particularly fond of most kids, even my own on certain days. Then I told her the team we were on.

The New York Giants.

Later that evening, we told our son, and he was absolutely over the moon. He was officially a Giant.

The First Practice

Our first practice was kind of a blur. A bunch of kids, parents, one play we pulled from YouTube, and all of us trying to figure things out at the same time. I watched the kids closely, tried to get a sense of who fit where, and started assigning positions.

I put Michael at receiver, even though he was still figuring things out himself, which was a classic parent-coach move. In reality, everyone except the quarterback is a receiver, but having the title adds to the coolness factor.

We had two kids named Matt. One of them was tall, so we called him Tall Matt. He became our quarterback. He could see down the field over the other kids and had a pretty good arm.

We had one play. Four kids to throw to. No run plays. Just one passing play. One thing I’ve always been obsessed with is habit formation. It doesn’t matter what you’re trying to learn. You have to do it over and over until it’s so committed to memory that you don’t even think about it anymore. It just happens. We practiced that one play exactly like that. The timing, the feel, the looks from the quarterback, everything.

Game day rolled around and we met up before the game. I’ve always done things a little differently. It’s just part of who I am. I talked to the kids, had them throw the ball a bit, ran the play once or twice, and then said, “Okay, let’s just chill for the next ten minutes.” I had them sit on the grass, look up at the sky, and think about anything but football. Think about vacations, video games, anything. There was nothing left to fix. No amount of last-minute practice was going to change anything now.

The whistle blew, we marched onto the field, and we collectively beat our opponent soundly, like we had been playing together forever.

New coach. New team. We were 1-0.

We went into the second game feeling unstoppable. My wife looked on, probably wondering how it was even possible that her husband had just led a group of kids to victory with little more football knowledge than what he’d absorbed watching games on TV over the years.

This game did not start well. We were a small team physically, and the opponent was huge. Our first offensive drive stalled immediately. On defense, they marched right down the field and scored. Nothing was working.

I called a timeout and talked to Tall Matt. I called my son over and told them the truth. We were basically screwed if we didn’t do something different. I told Tall Matt he was switching with Michael. Tall Matt would be the receiver. Michael would be the quarterback. Michael was solid at throwing by this point and could throw some serious darts. I had only put him at receiver originally because his idol was Odell.

I told them exactly what was going to happen. Michael was going to throw to Tall Matt, and only Tall Matt. He was the only one tall enough to be open. If parents or teammates complained, I would smooth it over.

The rest of the game went better. Michael hit Tall Matt for two touchdowns, and we won 14-13. We finished the season with a winning record, which was pretty cool for our first season.

Michael was hooked. I was hooked. And that was the beginning of a partnership that would go on for the next eighteen or so seasons.

We signed up immediately for the next season and tried to start practicing earlier than we had the first season, when we’d only had two or three weeks to prepare.

Training for What Doesn’t Show Up on Game Day

I mentioned earlier that I did things and thought differently, and nowhere was that more apparent than during practices. The looks I would get from parents during the first few practices made that clear almost immediately.

I was the first coach I knew who brought a plyo box to practice. It was made of plywood and weighed a ton. Parents looked at me like I was nuts. But jumping matters. I explained to the kids that when game time comes, you don’t suddenly rise to the occasion. If you do, it’s luck. You jump the way you’ve trained to jump. If you want to go up and grab a ball or intercept a pass, those muscles have to already know what to do. The plyo box was how we trained that.

I was also the first person I’d seen bring a BOSU ball to practice for balance training. Balance is one of those things that quietly affects everything else. Running, jumping, agility, stability, cutting, catching. If balance is off, everything downstream suffers.

The kids would start practice with jumps on the plyo box, from the left, right, and front. Then they would move to the BOSU ball. One kid would balance while another threw to him. Then they would switch. It was high-level Mr. Miyagi stuff, whether the parents realized it or not.

We also warmed up with tennis balls at practice and before games. Tennis balls were useful for a few reasons. If a kid was dropping passes, I’d pull him aside and have him catch twenty-five throws with a tennis ball. It forced focus. Eyes on the ball. Hands doing the work. After that, he’d go back in and the drops would usually disappear.

Our game-day warmups looked different too. We didn’t do the intense, loud routines other teams did. The quarterback would throw to players running basic routes. We’d mix in tennis balls. From the outside, we probably looked soft.

We weren’t.

We were small, fast, and trained. We usually decimated most teams.

I remember one parent coming up to me before a game and saying, “Did you see the size of that other team?” I told him not to worry and that we were going to tear them apart. We did.

We even practiced for rainy games by putting water on the football so kids could get used to catching a slick ball. For defense, we used a modified tackle drill to teach kids to grab both flags. Most kids reached stiff and upright. We trained them to crouch, go in with both hands, and force the runner to slow down or change direction. That did three things at once. It increased reach, improved flag pulls, and disrupted momentum.

None of this looked flashy. But it worked.

Learning

I had a lot of ideas about how to be better, and so did Mike. We started training and getting ready more deliberately. One thing I discovered was that I liked designing plays and figuring out the opponent. That part surprised me. I had never been a coach. Kids had always kind of weirded me out, other parents often seemed annoying, and the whole thing felt strange at first.

What I learned, though, was that training kids and mentoring them was actually very rewarding. Parents would tell me, “You must be the best dad,” and I would say thank you while thinking to myself, honestly, that I wasn’t that great of a dad. And I wasn’t. My wife and I met when I was thirty-eight. She already had three kids, and Michael was the fourth. That’s a complicated situation, even when everyone has good intentions.

I was adopted, so I never really thought in terms of stepkids. I looked at our daughters as our daughters. Sometimes that works. Sometimes it doesn’t. I wasn’t a very good dad to them, especially early on. They were pre-teens heading into the chaos of adolescence, and I arrived late to the picture with very little parental seasoning. Unsurprisingly, it didn’t work out the way I thought it would.

If I had known then what I know now, things would have gone much better. But I didn’t. I was thirty-eight and had never had kids. I found it difficult to relate at first, and by the time I could see their side of things and develop real empathy, it was already too late. Being a stepdad, even when you think you’re just “dad,” is a hard role to fill. Almost everyone resents the step-parent at some point.

So back to football.

We had an entirely new team except for my son, which I hadn’t really anticipated. I had somehow assumed we would always have the same group of kids. That season taught us a lot, but again we finished with a winning record only to get absolutely smoked in the first round of the playoffs. We didn’t even know what hit us. Playoff football is different. Teams are sharper, kids are more intense, and suddenly what worked all season stops working entirely. It felt like stepping onto train tracks and getting hit by a freight train.

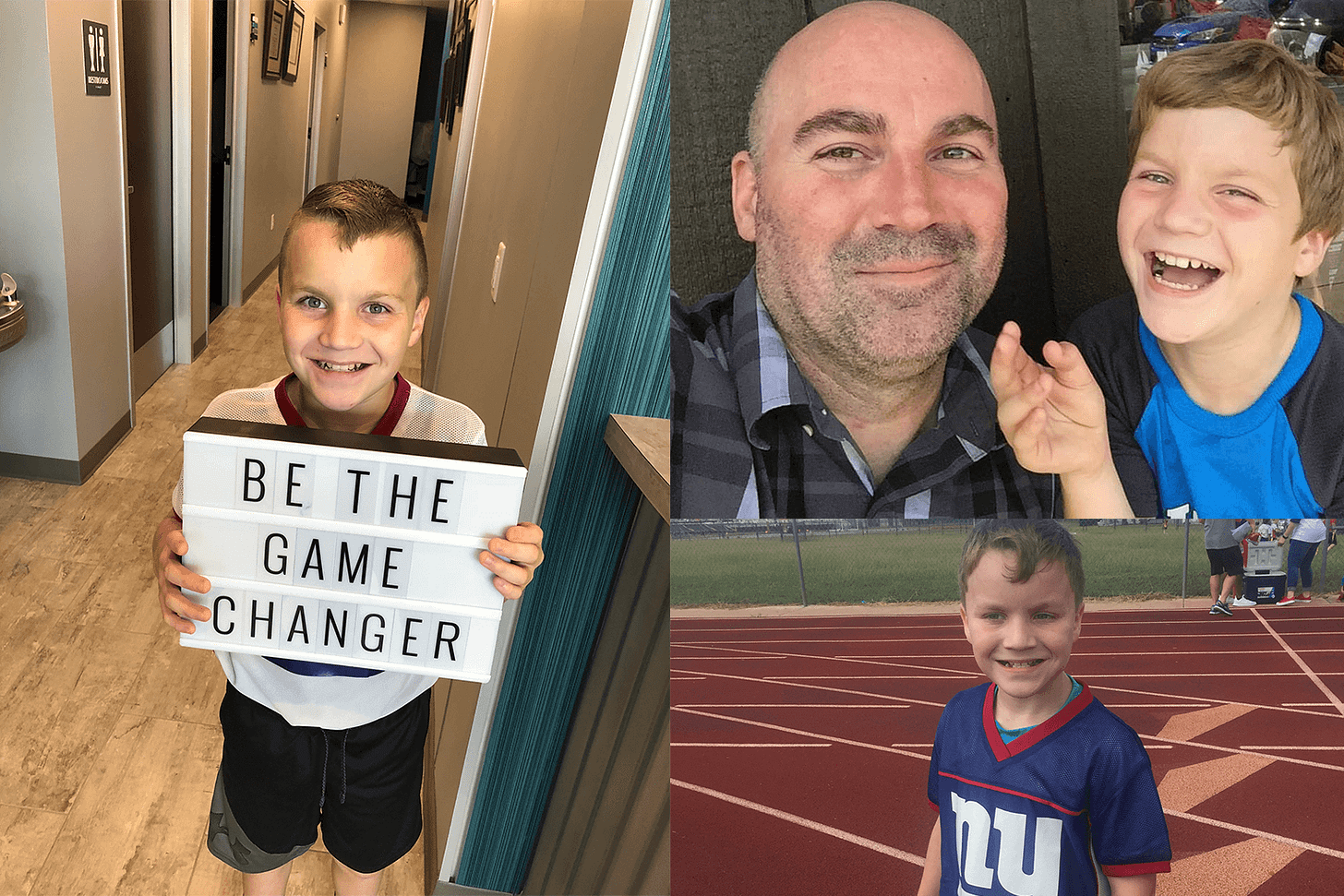

By the time season three came around, I was starting to figure things out. Mike was becoming one hell of a player, and I’m not saying that just because he’s my son. Parents would ask why he wasn’t in during critical moments, and I’d explain that we rotate kids to be fair. Sometimes, and I’m not exaggerating, parents would demand that Michael be in over their own kid because the moment mattered. I wasn’t delusional. He really was that good.

We had a kid on our first team named Sean, affectionately known as Cry Baby Sean Doll. He was fine with the nickname, though most people just called him Sean. He cried a lot, but he was lightning fast. The first time around, he had been one of our receivers.

I reached out to his parents before the season and asked if he could join the team again. I told them I had learned a lot since the first season, that their son was well liked, and that I thought I knew exactly how he should fit this time. They agreed.

When they brought him to practice, they asked what my plan was. I told them he was going to be our running back. He would run the ball. This surprised them. They had always pictured him as a receiver and even suggested that this might not be a good idea.

I stuck with the plan. My son and another player were our top receivers, my son’s friend from school had joined as our permanent quarterback, and Sean was our running back. I had designed plays that worked with each kid’s strengths while minimizing their weaknesses.

When the season started, everything clicked. We were dominant. Routes were crisp, Sean was untouchable, and it all just worked. It was amazing.

Midway through the season, Sean’s parents came up to me with tears in their eyes. They told me that Sean had always wanted to run the ball, but they had pushed him to be a receiver instead. They were grateful that I saw something in their son that they had missed. It was a special moment.

We finished the season with our best record yet.

Flag to Tackle to Varsity

We played every season consecutively except for the COVID year when all sports were canceled. Some seasons we were undefeated. Many others we lost only one game. Not bad for a kid who couldn’t catch and a dad who couldn’t coach.

A one-handed interception at linebacker as a freshman. ;-)

As Michael entered middle school, we debated tackle football. He was eligible to play in seventh grade, but we decided to wait and stick with flag for one more year. Tackle can be rough early on, and we were concerned about injuries. That concern was reinforced when a kid from our flag team played seventh-grade tackle, got injured badly in practice, wore a brace for over a year, and never played football again.

Ironically, Michael was tailor-made for tackle football. We’re both stocky builds. In flag, someone just has to grab your flag. In tackle, you actually have to stop the player. Given his size, the idea of transitioning him to running back also came up. He wasn’t tall and didn’t fit the prototype many coaches look for in high school or college receivers.

His first year of tackle was eighth grade. He had never played it before, but he was fantastic. He was the most impactful player on the field. He played offense, defense, and special teams. He had games with multiple interceptions on defense and multiple touchdowns on offense. A legitimate standout.

That middle school team won almost every game. I was also adjusting to not being his on-field coach anymore. My wife had spent years on the sidelines alone, so it was good to stand next to her for a change. It took some getting used to. I still worked with Michael on plays and technique, but my role shifted from coach to trainer and motivator.

A pick as a safety in the 8th grade.

That transition carried us into high school football. Writing this, I’ve cried several times. I know this phase is changing again, and soon he’ll be off to college.

Michael became very focused on strength entering his freshman year. We had always played up an age group in flag, so he was used to size differences, but tackle added another level entirely. He lived in the gym all summer, maybe too much. He built a lot of muscle. He even got my wife and me into lifting.

During those years, our routine changed. We talked more seriously about life, leadership, and responsibility. Before every game, I sent him what some might consider intense text messages. That tradition continues to this day. He’s a junior now.

The clock is on 26 seconds, and his number is 26. What happens next is fate.

Those messages were part strategy, part motivation, and part hard truth, like something a boxing coach might say before a fight. Maybe I should have sent one to Jake Paul the other day.

His freshman year was excellent. He played offense, defense, and special teams, usually sitting only one drive to rest. His sophomore year on JV was much of the same. His junior year was harder. He made varsity, but for the first time he didn’t get heavy playing time. Seniors were ahead of him and needed their final season.

That year bonded us in a different way. He had always been the standout, the kid everyone relied on. Now he had to wait. When he did get the ball, he made it count. Next year he’ll be a senior, and it should be one hell of a season.

Seventeen Going on Thirty

My kid is growing up. Almost a full-grown man. His skills are solid, and so is he. This year, without prompting, he decided to apply himself academically. For the first time, he wanted great grades, not just good enough grades to play sports. He’s pulling As and Bs.

He’s seventeen going on thirty. We’re friends, but I’m still dad. We managed to navigate that line that trips up so many parents. We’re close, but he listens and knows where the boundaries are. We don’t fight. He’s far more together than I was at his age, and it shows.

I love him, and he loves me.

A Father and Son Odyssey.

To be continued.

Help Keep This Work Independent

Preparation does not announce itself.

It happens quietly, over time, long before the moment arrives when it matters.

This essay is not about football. It is about what repetition builds, what responsibility teaches, and how judgment is formed when someone stays with a thing long enough to understand it. That is the same discipline behind this Substack.

If this piece helped you recognize something you’ve lived but never quite articulated, the next step is simple. Support the work that stays honest while much of the rest of the media adjusts itself to incentives, trends, and pressure.

Become a Paid Subscriber

Paid subscribers make this work possible. They fund long-form writing that is built to last, not to perform. Writing that relies on experience, context, and evidence rather than slogans or outrage.

If you value work that prepares you before the moment arrives, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

https://mrchr.is/help

Make a One-Time Gift

If a subscription is not right for you, a one-time contribution still matters. It helps cover research, writing time, and the practical costs of keeping this work independent.

Join The Resistance Core

This option is for readers who believe this work is worth more than a monthly subscription and want to make a larger statement of support.

The page defaults to $1,200 per year, but you can adjust it to $500, $1,000, $2,000, or any amount that makes sense for you.

Think of it as a once-a-year vote for work that values preparation over performance and substance over slogans.

If You Cannot Give

Sharing this essay with someone who values clarity, discipline, and preparation still helps. That kind of reader is why this work exists in the first place.

Sign Up for the Boost Page — Free

If you are a writer or creator on here, this is a free way to strengthen distribution without relying on platforms that reward distortion and noise. We can support each other.

Thank you for reading.

Thank you to those who have already supported this work.

I don’t take it for granted.

I believe in this work.

I believe in where it’s going.

And with your help, I’ll keep doing it the same way.

Awesome post. You and you wife are doing a great job.

You've got to be proud the legacy you're raising.