A Time for Choosing – Then and Now

How Reagan warned, Venezuela proved, and America still followed

A Note to the Reader

In the previous essay, How Venezuela Was Built to Fail (By Us), I argued that Venezuela did not collapse because of ignorance, bad luck, or even ideology alone. It collapsed because a wealthy country taught its people to confuse distribution with production, comfort with stability, and government management with moral progress. Oil did not ruin Venezuela. Incentives did.

That argument unsettled some readers because it challenged a comforting assumption. Namely, that what happened there could not happen here. That America’s wealth, institutions, and intentions make it immune to the same laws of economics and human behavior.

This essay begins where that one ended.

What follows is not a claim that the United States is Venezuela, or that collapse is imminent. It is something more uncomfortable. It is an examination of how the same incentive structures that hollowed out Venezuela are now visible inside a far richer, more advanced society, operating under different names and better branding.

If the first essay explained how a country was dismantled through dependency, debt, and institutional decay, this one asks a harder question.

What happens when the same logic is applied slowly, politely, and at scale?

That is the context for what follows.

“You cannot build a free society by teaching people to live off what they did not earn and trust institutions they cannot control.”

On the night of October 27, 1964, a former actor sat before a television camera and delivered what remains one of the clearest warnings ever issued about the future of American freedom. He was not yet a governor or a president. He held no office and commanded no institution. He spoke only as a citizen who had thought carefully about incentives, power, and human nature.

His name was Ronald Reagan. The speech was titled A Time for Choosing.

Reagan warned that when a people trade responsibility for comfort, liberty does not vanish overnight. It dissolves gradually, wrapped in good intentions and administrative language. He said the real divide in politics was not left versus right, but up toward freedom or down toward control. Those who sought security through government management were not buying peace. They were buying dependence, and dependence always comes with conditions.

At the time, the warning sounded dramatic. America was wealthy, confident, and expanding. Suburbs multiplied. Manufacturing dominated the world. The dollar was strong. Government programs grew, but few worried about permanence. The assumption was that a prosperous republic could afford inefficiency, debt, and bureaucracy without consequence.

That assumption has not survived contact with reality.

Sixty years later, nearly every condition Reagan described is visible, not in its harshest form, but in its most seductive one. Control no longer arrives with uniforms or slogans. It arrives through forms, incentives, and experts. Dependency is no longer a sign of failure. It is treated as a civic virtue. Citizens are told that managing their own health, energy, finances, or speech is too complex and too dangerous to be left to ordinary people. Qualified professionals must guide them.

What Reagan called the ant heap of totalitarianism did not require tyranny to function. It only required comfort without discipline and power without accountability.

He warned that government cannot control the economy without controlling people. In 1964, critics called that exaggeration. In 2026, it reads like an observation. Regulation now shapes where people work, what they build, what they say online, what energy they use, and how they are allowed to transact. None of this required the repeal of the Constitution. It required only the steady expansion of administrative authority, coupled with public fatigue.

The United States has not lost freedom through invasion. It has misplaced it through delegation.

Reagan also said that if freedom failed here, there would be nowhere left to escape. At the time, Europe was rebuilding, Asia was rising, and the developing world looked open. Today, Europe faces demographic collapse and bureaucratic paralysis. Much of Asia operates under surveillance states. The developing world increasingly blends crony capitalism with censorship. There is no other large, wealthy republic left to absorb failure here.

This is not nostalgia. It is context.

The question Reagan posed sixty years ago has returned in a new form. Do Americans still believe they are capable of self-government, or have they accepted a managed life as the price of stability?

There is no left or right in that question. There is only up or down.

The Revolution of Comfort

Self-government requires discipline. Discipline requires discomfort. That simple chain explains more about the decline of free societies than ideology ever could.

America’s cultural decay did not begin with hatred of freedom. It began with success. The postwar generation that built highways, factories, and research institutions also created the expectation that abundance was permanent. Over time, prosperity stopped being the product of effort and became the baseline assumption. Citizens learned to measure success in consumption rather than contribution.

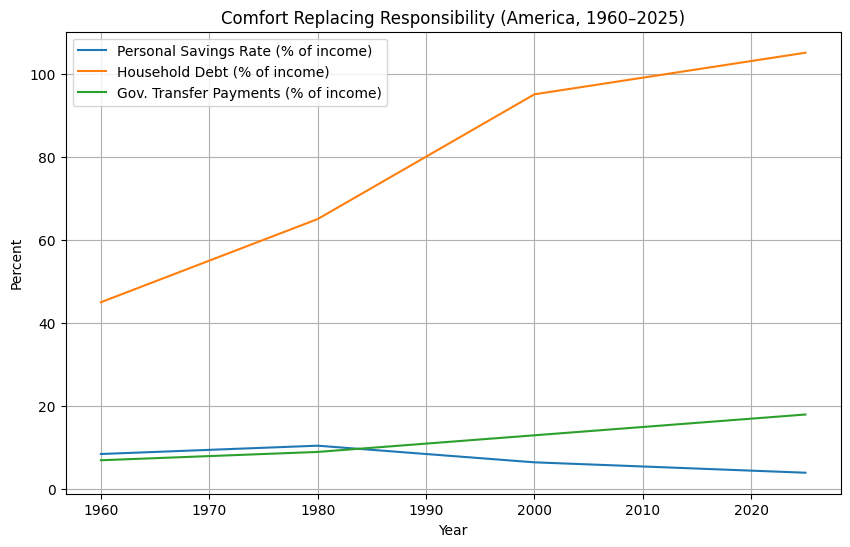

Savings rates tell part of the story. In the 1950s and early 1960s, Americans regularly saved more than 10 percent of their income. By 2025, personal savings fluctuated between 3 and 5 percent, spiking briefly during crisis and collapsing afterward. Consumption did not fall. It was financed through debt and transfer payments. The American Dream gradually became the American installment plan.

This shift was not merely financial. It was cultural. Work became transactional rather than formative. The family, once the primary institution of responsibility and meaning, became optional. As marriages declined, government programs quietly expanded to fill the gaps left behind. Dependency grew not because people were lazier, but because incentives changed.

Time use data reflects the transformation. The average American adult now spends more than seven hours a day consuming digital media. That figure includes work-related screen time, but a large share is entertainment and social media. This level of distraction has no historical parallel. A population absorbed in constant stimulation does not organize, does not study tradeoffs, and does not resist gradual encroachment. It scrolls.

This pattern is not unique to America. It appeared earlier in Venezuela, though through cruder mechanisms. During the oil boom of the 1970s, state revenue insulated the population from economic reality. Imports surged. Domestic production shrank. Subsidies expanded. Politics shifted from problem-solving to distribution. Citizens became clients of the state, not participants in a productive economy.

When Hugo Chávez arrived decades later, he did not invent dependency. He exploited it. The culture of comfort was already in place. He merely promised to manage it more aggressively. The result was not equality, but shared fragility.

America’s version is more sophisticated. Instead of oil revenue, it uses credit. Instead of blunt propaganda, it uses lifestyle language. Wellness replaces discipline. Emotional safety replaces resilience. Surveillance is rebranded as personalization.

The social indicators reflect the cost.

Marriage rates have fallen by roughly 60 percent since 1970. Birth rates are down about 40 percent. Church attendance has been cut in half. Opioid overdoses now exceed the total number of U.S. combat deaths in the Vietnam War every few years. The share of prime-age men not participating in the labor force has increased severalfold since the mid-twentieth century.

These are not isolated statistics. They describe a failure of meaning. A society that cannot persuade its citizens to form families, build skills, and accept responsibility will eventually require management instead of leadership.

Reagan once remarked that the problem with many liberal thinkers was not ignorance, but confidence in things that were not so. That insight applies here. We possess unprecedented amounts of information and diminishing understanding. We talk endlessly about self-care while neglecting self-command. In trying to eliminate discomfort, we have weakened the habits that make freedom possible.

The revolution of comfort does not require censorship. It succeeds through exhaustion. A population overwhelmed by novelty loses interest in long-term thinking. Emotion replaces reason. Politics becomes a contest of reassurance rather than consequence. At that point, manipulation becomes easy.

Venezuela entered this phase before it became poor. America is entering it while still wealthy. History suggests that wealth delays consequences but does not prevent them.

What fails first in such societies is character. Competence follows. Currency comes last.

Governments can print money, create programs, and produce slogans. They cannot manufacture will. Once a culture loses the habit of self-restraint, external control fills the vacuum.

This is not a moral lecture. It is an observation drawn from repeated outcomes. Comfort erodes independence. Independence erodes slowly. Collapse comes quickly.

Reagan warned that freedom requires constant effort. That effort is unpopular in comfortable times. But no civilization has ever survived on convenience alone.

We are again at a time for choosing, not between parties, but between responsibility and management.

Debt as the New Oil

Every society runs on a primary resource. For Venezuela, it was oil. For modern America, it is debt.

Debt is more intoxicating than petroleum because it feels painless. It requires no drilling, no engineering, no visible sacrifice. It is created by keystroke, distributed by statute, and justified by moral language. Like oil revenue once did in Caracas, borrowing allows politicians to postpone tradeoffs and purchase social peace without asking the public to produce more.

For decades, American politics has operated on a simple discovery. Borrowing buys quiet. Programs can expand, benefits can grow, and taxes can remain politically tolerable as long as the bill is sent forward in time. Each generation consumes today and invoices tomorrow.

The numbers tell the story without rhetoric.

In 1980, total U.S. federal debt stood just under $1 trillion, roughly one-third of national economic output. By 2000, it had climbed to $5.6 trillion. By late 2025, total federal debt exceeded $38 trillion, hovering around 120 percent of GDP and rising by well over $2 trillion per year. Even optimistic projections from the Congressional Budget Office now assume debt will continue climbing indefinitely as a share of the economy.

This is not a temporary emergency. It is the baseline.

Net interest costs now rival, and in some periods exceed, annual defense spending. That means a growing share of federal revenue is consumed before a single program is funded or a single service is delivered. Interest pays for nothing tangible. It maintains the illusion that the system can continue unchanged.

Reagan warned in 1964 that no nation had ever survived a tax burden approaching a third of national income. Today the burden is not simply taxation, but obligation. Promised benefits vastly exceed projected revenue. Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid already consume roughly two-thirds of federal spending. Add interest, and the discretionary portion of the budget shrinks to a narrow band fought over each year with increasing desperation.

Yet campaigns continue to promise new benefits. Free college. Forgiven loans. Guaranteed income. Expanded healthcare. Each promise is framed as compassion. None includes a credible funding mechanism that does not rely on further borrowing or inflation.

Debt has replaced work as the political currency of choice.

This pattern is not unique. Venezuela followed the same logic during its oil boom. Revenue funded expansive welfare programs, public employment, and price controls that insulated the population from market signals. When oil prices fell, the government borrowed. When borrowing failed, it printed. Each step delayed adjustment while magnifying collapse.

America’s advantage has been the dollar’s reserve-currency status. Global demand for dollars has allowed borrowing on terms no other country could sustain. But reserve status does not repeal arithmetic. It merely slows the reckoning.

The consequences already appear in distorted incentives. Savers are punished through inflation. Speculators are rewarded. Asset prices inflate faster than wages. Young people are pushed into debt early and told that rising prices are normal. The dollar today buys less than five percent of what it did when Reagan gave his speech. This is not accidental. Inflation is the quiet tax that finances promises politicians refuse to fund honestly.

Debt does more than weaken currency. It reshapes character. A society that normalizes borrowing against the unborn erodes the concept of responsibility itself. Consent disappears when costs are imposed on people who cannot vote yet. This is dependency disguised as generosity.

Venezuela reached this stage when its middle class realized it was paying for programs it no longer benefited from. The productive fled. The remaining population depended increasingly on the state. By the time hyperinflation arrived, social trust was already gone.

America is earlier in the process, but the direction is familiar. When consumption no longer requires production, politics replaces enterprise. When promises outpace resources, enforcement replaces consent.

This is not a partisan problem. It is a structural one. Debt addiction survives elections because it rewards everyone in the short term and punishes no one immediately. Politicians gain power. Voters gain benefits. Bureaucracies expand. Only the future loses.

Reagan understood that sound money was not a technical detail but a moral one. A stable currency rewards patience, work, and planning. A collapsing one rewards leverage, speed, and political proximity. Venezuela’s inflation destroyed not only wages, but trust. America’s inflation is doing the same more quietly.

The danger is not that the system will collapse tomorrow. The danger is that it will drift until correction becomes politically impossible.

When interest consumes the budget, choices narrow. When choices narrow, control expands. When control expands, freedom contracts.

Debt is not neutral. It is power exercised across time. And like oil revenue once did in Venezuela, it convinces a population that prosperity is permanent and discipline optional.

History suggests otherwise.

Institutions, Regulation, and the New Clerisy

Every expanding system develops a class whose primary function is to manage it. Over time, that class acquires interests distinct from the people it claims to serve. When those interests harden, reform becomes not merely difficult but unwelcome.

America has reached that stage.

Reagan warned that government cannot control the economy without controlling people. What he understood, and what many still miss, is that control rarely appears as tyranny. It arrives as expertise. The modern administrative state governs not by law alone, but by rulemaking, guidance, interpretation, and enforcement discretion exercised by people most voters will never meet and cannot remove.

This is what economists describe as regulatory capture, though the term understates the problem. Capture suggests corruption. What actually happens is alignment. Agencies, industries, media, and credentialed professionals gradually come to share the same worldview, incentives, and vocabulary. Once that occurs, failure is never attributed to the system itself. It is blamed on insufficient funding, insufficient authority, or insufficient compliance.

Venezuela’s oil industry provides a stark illustration. After nationalization in the 1970s, the state oil company PDVSA was initially staffed by competent engineers. Production peaked near 3.5 million barrels per day. Over time, political appointments replaced technical expertise. Management decisions served loyalty rather than output. By the mid-2010s, production had collapsed below 1 million barrels per day. The machinery did not fail first. Governance did.

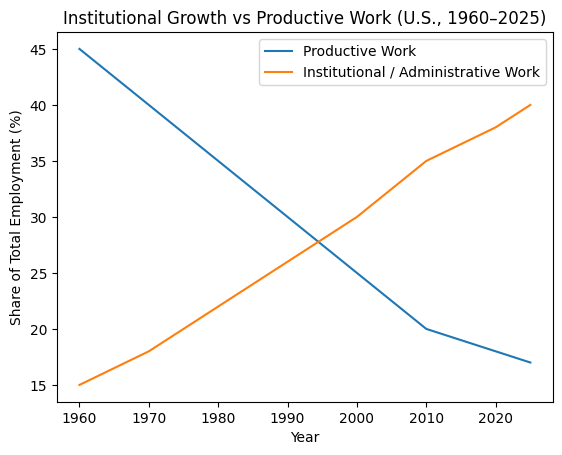

The United States has not nationalized its industries outright, but it has bureaucratized them. Regulation now shapes nearly every sector of the economy, from healthcare and finance to energy and education. The Federal Register publishes tens of thousands of pages of new rules each year. No citizen reads them. Most lawmakers do not either. Authority migrates to specialists whose power lies in interpretation.

The effect is predictable. Large firms adapt. Small firms struggle. Compliance costs fall hardest on those without legal departments. Regulation advertised as consumer protection becomes a barrier to entry. Competition shrinks. Concentration grows. The result is not less power, but power redistributed upward and inward.

This is not an accident. It is the incentive structure.

By 2026, credible estimates place the cost of complying with federal regulation in the trillions each year. That figure does not represent productive output. It represents time, labor, and capital diverted into documentation, reporting, and permission. Economists have long noted that when compliance costs rise, innovation slows. The firms most able to navigate complexity are the ones already established.

Thomas Sowell spent decades documenting this pattern. He observed that many policies sold as protections for the weak end up protecting the strong by raising the cost of participation. What looks like compassion in theory becomes exclusion in practice.

Alongside regulation has grown a professional class that administers it. Call them experts, administrators, or stakeholders. Historically, they were called the clerisy. Their defining trait is not intelligence, but insulation. Their income, status, and authority depend on the continuation of the systems they manage. Failure therefore becomes existential. A program that solves its problem would justify its own reduction. That rarely happens.

Government employment illustrates the shift. In the 1960s, federal employment stood around 2.5 million. By 2025, when state and local government are included, nearly one in six employed Americans draws a taxpayer-funded paycheck. This does not include the millions more employed by firms whose primary customers are government agencies.

The economy has developed a large constituency that benefits directly from administrative expansion. That constituency votes, donates, advises, and appears on television. Its worldview becomes normal.

Education reinforces the pattern. Universities increasingly function as credentialing pipelines rather than places of debate. Administrative spending has grown far faster than instructional spending over the last two decades. Humanities enrollment has fallen sharply, while compliance offices, diversity departments, and regulatory programs have multiplied. Graduates enter the workforce fluent in policy language but often unfamiliar with production, logistics, or cost.

This matters because policy designed without exposure to consequence tends to repeat itself regardless of outcome. When a regulation fails, the diagnosis is rarely that the premise was flawed. The conclusion is that enforcement was insufficient or that the public failed to comply correctly.

Media alignment completes the system. Major outlets rely on access to officials, advertising from regulated industries, and audiences conditioned to expect reassurance. Investigating institutional failure risks access and revenue. Reporting therefore drifts toward narrative maintenance. Problems are framed as unfortunate but necessary side effects of progress.

Venezuela followed the same path in cruder form. State media reinforced official explanations. Private outlets were marginalized or absorbed. Criticism was redefined as sabotage. America’s version is subtler. It does not silence dissent outright. It marginalizes it through expertise and tone. Critics are labeled uninformed, extreme, or irresponsible.

Over time, institutions stop asking whether policies work and start asking whether they align with approved language. Truth gives way to procedure. Responsibility gives way to process. This is how bureaucracies protect themselves.

Reagan understood that free societies depend on accountability. Authority must be traceable. Decisions must be reversible. When power disperses into agencies, boards, and partnerships, responsibility evaporates. No one is in charge, yet everyone enforces.

The result is a system that expands even as trust collapses. Citizens sense that decisions are being made beyond their reach, but cannot identify who to hold accountable. Participation declines. Cynicism rises. Control increases to compensate.

This is not unique to the Democrat Party, but it has been embraced most aggressively by it. The party’s modern strategy relies heavily on administrative governance, judicial interpretation, and cultural enforcement rather than persuasion. Policy is implemented through agencies when legislation proves unpopular. Opposition is framed as ignorance rather than disagreement.

History suggests this model has limits. Systems that cannot correct themselves eventually exhaust legitimacy. When that happens, enforcement replaces consent.

The tragedy is that many participants in this system believe they are acting in the public interest. That belief makes reform harder, not easier. People who see themselves as guardians rarely accept constraints.

Venezuela collapsed when institutional failure became undeniable. America is earlier, wealthier, and more resilient. But the underlying mechanics are familiar. A governing class insulated from consequence will continue expanding authority until reality intervenes.

No society can regulate its way to virtue. No bureaucracy can substitute for responsibility. The more management replaces judgment, the less capable citizens become.

Reagan warned that freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction. Not because people forget laws, but because they forget why limits exist.

Information Control and the Security State

Every governing system eventually discovers that persuasion is cheaper than force. When persuasion falters, it learns that fear is cheaper than either. Modern America has fused both lessons into a system that controls behavior less by command than by conditioning.

Reagan warned that freedom can disappear within a single generation if people forget what it looks like. What he did not fully foresee was how thoroughly technology would change the mechanics of forgetting. Control no longer depends on censorship alone. It depends on saturation. Instead of suppressing information, modern systems drown it.

The Soviet Union needed censors and guards. Venezuela relied on state television and party loyalty. The American model is quieter. It works through partnerships between government agencies, corporate platforms, universities, and media outlets, all operating within legal boundaries that technically preserve the First Amendment while rendering it less effective in practice.

The shift began after September 11, 2001. In response to legitimate security threats, Congress created the Department of Homeland Security and vastly expanded surveillance authority. At the time, DHS employed roughly 170,000 people with a budget near $25 billion. By 2025, its combined reach across agencies, grants, and programs exceeded $100 billion annually. Emergency powers became permanent tools.

Each expansion was justified. Terrorism, cybercrime, pandemics, misinformation, extremism. Every crisis produced a new rationale for monitoring, coordination, and data sharing. None came with a meaningful sunset.

By 2026, most Americans carry devices that record location, communication, purchases, and behavior continuously. That data is collected by private companies for profit. Government agencies increasingly acquire it through contracts rather than warrants. The Fourth Amendment still exists, but its assumptions do not. What once required probable cause now requires a purchase order.

The result is surveillance by proxy. Law enforcement and intelligence agencies no longer need to compel cooperation. They rent it. Data brokers sell information that allows agencies to map social networks, political associations, and behavioral patterns without judicial oversight. Courts have struggled to keep up because the surveillance is technically voluntary. Citizens agreed to the terms of service.

Fear completes the loop.

The COVID pandemic demonstrated how quickly emergency authority can override ordinary debate. Within weeks, administrative agencies closed businesses, churches, and schools. Legislatures were sidelined. Press conferences replaced votes. Some measures were defensible in the moment. Others were not. What matters is that the precedent was established.

Once fear becomes the justification, boundaries blur. Since 2021, the phrase national emergency has been used to support executive actions on public health, climate policy, border enforcement, and infrastructure. An emergency without a defined endpoint is no longer an exception. It is governance by alarm.

Thomas Sowell wrote that the vision of the anointed rests on the belief that some people know what is best for everyone else. The security state operationalizes that belief. Risk is redefined as disobedience. Dissent becomes irresponsibility. Citizens are treated less as adults capable of judgment and more as variables to be managed.

Information control reinforces the system. Government agencies increasingly coordinate with social media companies under the banner of fighting misinformation. Court filings and congressional testimony released between 2023 and 2025 revealed regular communication between federal offices and major platforms, flagging content for removal or suppression. Officials insisted these were requests, not commands. The distinction is largely academic when regulatory power looms in the background.

This is soft censorship. It does not ban speech. It buries it. Algorithms reduce reach. Labels discredit sources. Payment processors restrict monetization. None of this requires a law. It requires alignment.

Trust in media has collapsed as a result. In the mid-1970s, roughly two-thirds of Americans said they trusted the press. By late 2025, fewer than 30 percent did. Consolidation has reduced diversity of perspective. Five major corporations control the majority of national news distribution. Their incentives favor stability, access, and narrative coherence over investigation.

Venezuela followed a similar trajectory with fewer technical refinements. The government controlled the airwaves directly. The American system controls distribution indirectly. Both achieve the same end. A public less capable of distinguishing information from instruction.

Financial surveillance deepens the control. Under anti-money laundering rules expanded since 2010, banks report increasingly small transactions automatically. By 2026, transactions over $600 may trigger reporting requirements. At the same time, the Federal Reserve continues experimenting with a digital dollar framework, marketed as convenience and efficiency.

Digital currency centralizes visibility. Every transaction becomes traceable. In isolation, that seems benign. Combined with social enforcement mechanisms, it becomes powerful. China has already demonstrated how financial access can be conditioned on behavior. The United States has not adopted that model formally, but private companies have practiced it in miniature. Accounts have been frozen or services denied for political reasons without court orders.

Control no longer needs to imprison. It excludes.

When banking, employment, communication, and transportation depend on compliance with opaque rules, citizens learn to self-censor. The most effective control is internal. People begin asking not whether something is true, but whether it is safe to say.

This environment produces exhaustion. A population flooded with contradictory claims eventually stops evaluating evidence and retreats into identity. Facts become tribal markers. Emotion replaces analysis. Politics becomes therapeutic rather than corrective.

Reagan warned that government should protect people, not run their lives. The modern security state blurs that distinction deliberately. Protection becomes management. Management becomes supervision. Supervision becomes permission.

History shows where this leads. Venezuela justified internal checkpoints as anti-smuggling measures. They became tools of political control. Surveillance always expands faster than its stated purpose.

Fear is useful when it warns. It is destructive when it governs. A society that treats risk as unacceptable will accept almost any intrusion in exchange for reassurance.

The tragedy is that many participants believe they are preventing harm. That belief makes restraint unlikely. Systems built on fear do not contract voluntarily. They require resistance, accountability, or failure.

America still has all three options. But time matters. Once surveillance becomes normal and dissent becomes dangerous, reversal grows harder.

Freedom does not disappear when people are arrested. It disappears when they decide it is safer not to speak.

Energy Dependence and Moral Theater

Energy is not a lifestyle preference. It is the foundation of modern life. It determines whether factories operate, food is affordable, hospitals function, and homes remain livable. Societies that misunderstand this tend to moralize energy policy until physics reasserts itself.

Reagan understood this plainly. In 1981 he warned that energy independence was not a talking point but a form of national insurance. A country that cannot reliably power itself eventually surrenders both prosperity and autonomy.

Venezuela provided the clearest modern example of what happens when energy policy becomes political theater. With the largest proven oil reserves in the world, it should have been energy secure for generations. Instead, oil revenue became a tool for social management. Subsidies replaced maintenance. Loyalty replaced expertise. When prices were high, the damage was hidden. When prices fell, reality arrived all at once.

Oil production peaked near 3.5 million barrels per day in the late 1990s. By 2020, it had fallen below 700,000. Refineries failed. Gas stations ran dry. A country sitting on oceans of oil imported fuel. The collapse was not ideological. It was mechanical.

America is not Venezuela. But the incentives are drifting in a similar direction.

Energy policy in the United States is increasingly driven by moral signaling rather than engineering constraints. Politicians speak more about justice than kilowatts. Regulations close reliable power sources before replacements are built. The assumption is that intention can substitute for capacity.

Between 1980 and 2025, the number of operating U.S. oil refineries fell from over 300 to fewer than 130. Domestic refining capacity has barely grown since the mid-2000s, even as population increased by more than 90 million people. Coal, which supplied roughly half of U.S. electricity in 2000, now provides about 20 percent. Nuclear power remains stuck near 18 percent, despite decades of promises. Wind and solar have expanded rapidly, yet together still generate less than 15 percent of total electricity while receiving a majority share of federal energy subsidies.

These figures are not arguments against renewable energy. They are reminders of scale. Intermittent power cannot replace baseload power without massive grid expansion, storage capacity, and redundancy. Analysts inside the Department of Energy acknowledge that meeting current net-zero targets would require grid capacity increases exceeding 60 percent. At the same time, policies discourage investment in the very systems needed to stabilize that grid.

Germany attempted this transition first. Its Energiewende replaced nuclear power with renewables and natural gas. By 2022, more than half of its gas came from Russia. When that supply collapsed after the invasion of Ukraine, prices tripled and coal plants restarted. Moral ambition yielded to physical necessity.

California offers a domestic example. It mandates electric vehicles while importing roughly a third of its electricity from neighboring states. During heat waves, residents are asked not to charge cars at peak hours. This is not innovation. It is managed scarcity.

Dependence rarely announces itself honestly. It dresses as virtue. The United States now imports critical minerals for batteries and solar panels from countries that rely on forced or child labor. China controls roughly 70 percent of global rare earth processing and dominates battery supply chains. By 2026, most renewable infrastructure depends on components manufactured abroad by strategic rivals.

Reagan once used Saudi oil production to weaken the Soviet Union economically. That leverage came from self-reliance. A nation that dismantles its own capacity cannot apply pressure abroad. It can only absorb pressure at home.

Energy costs ripple outward. Since 2020, household electricity prices have risen roughly 30 percent in real terms. Manufacturing relocates to regions with cheaper power and fewer restrictions. Employment follows. Tax bases shrink. Debt expands. The same feedback loop that hollowed out Venezuela’s middle class now appears in milder form here.

Energy insecurity also reshapes governance. When power is scarce, governments decide who receives it first. Connected interests rarely wait in line. Venezuela began with rationing fuel. America uses regulatory credits and compliance incentives. The mechanism differs. The outcome is similar.

A society cannot power itself on virtue statements. Physics does not negotiate. Engineering does not vote. The longer policy ignores those constraints, the more coercion is required to enforce outcomes.

Reagan treated energy independence as a matter of national defense. Today it is treated as a branding exercise. That inversion explains much of the confusion in modern policy.

No civilization has ever regulated its way out of scarcity. It either produces energy or imports dependence. There is no third option.

Choosing Reality Again

Every society eventually faces a moment when narratives collide with consequences. At that point, adjustment becomes unavoidable. The only question is whether it happens early through reform or late through crisis.

Venezuela delayed adjustment until collapse. The United States still has time to choose differently.

This is not a question of ideology. It is a question of incentives. Systems that reward dependency will produce it. Systems that punish responsibility will erode it. No amount of rhetoric can reverse those outcomes.

Reagan understood that government cannot create virtue or prosperity. It can only preserve the conditions under which free people generate both. When government assumes the role of caretaker rather than referee, it displaces judgment with management. Over time, citizens lose the habit of self-command.

The modern American state is not tyrannical in form. It is managerial in spirit. It does not demand loyalty. It conditions behavior. It does not silence opposition openly. It marginalizes it procedurally. It does not confiscate property outright. It regulates it until use requires permission.

These are not dramatic changes. They are cumulative ones.

The Democrat Party has embraced this model most fully, relying on administrative power, cultural enforcement, and moral framing rather than persuasion. But institutions persist beyond parties. Once built, systems seek to survive. That is why reform must be structural, not symbolic.

The choice facing the country is simple to state and difficult to execute.

Do Americans trust ordinary people to make decisions and bear consequences, or do they prefer expert supervision with reduced risk and reduced freedom? Do they want responsibility with uncertainty, or management with guarantees that cannot be kept?

History offers no example of a society that maintained liberty by surrendering judgment. Comfort bought on credit always comes due. Surveillance justified by fear always expands. Regulation detached from accountability always concentrates power.

Reagan said Americans had a rendezvous with destiny. That rendezvous has not passed. It has been postponed repeatedly through debt, distraction, and delegation.

Reality is patient. It does not require belief. It only requires time.

The United States can still choose restraint over control, production over promise, and responsibility over dependence. But choices delayed become choices removed.

Venezuela stands as a warning, not because America is identical, but because human incentives are. Prosperity can anesthetize judgment. Moral certainty can excuse coercion. Bureaucracy can outgrow the people it claims to serve.

There is no escaping those patterns. There is only recognizing them early enough to change course.

This is again a time for choosing.

I Need You, Just Like You Need Me

This was not written to entertain you. It was written to warn you.

We are watching a slow-motion trade. We are trading our children’s futures for current comfort, our speech for social safety, and our independence for administrative permission. Most people will keep scrolling until the screen goes dark. Most people will wait for a “leader” to save them while they surrender the very habits—discipline, responsibility, and command—that make saving possible.

I do this full-time because I refuse to be one of those people.

There is no corporate board behind this. There is no foundation or NGO funding these words to make them “palatable.” There is only me, and there is you. When this writing stops, it isn’t because I ran out of things to say. It’s because the financial chokepoints finally closed, or because the lights went out.

If these words hit you in the gut—if they gave a name to the rot you’ve felt but couldn’t describe—then this is the moment to act. Don’t wait for the “collapse” to find your spine. Support the voices that are speaking while it’s still legal to do so.

Become a Paid Subscriber The “experts” want you dependent. I want you informed. Paid subscribers are the only reason I can keep the lights on and the research moving. Join us: https://mrchr.is/help

Make a One-Time Gift If you can’t commit monthly but you know this message needs to reach the people currently sleepwalking, a one-time gift keeps this platform fortified against the next crisis: https://mrchr.is/give

Join The Resistance Core For those who understand that a Substack is just a beachhead. This is for the readers who want to build something that cannot be throttled, bought, or silenced: https://mrchr.is/resist

If you truly cannot give, then do the one thing the system hates most: Share this. Send it to one person who still says, “It can’t happen here.”

Break the silence before the silence becomes permanent.

“Hard times create strong men. Strong men create good times. Good times create weak men. And, weak men create hard times"

We're as subject to the laws of human nature as any other civilization.

Throughout history, Republics last an average of 250-300 years before they decay and fall. Unfortunately, we're proving that the United States isn't going to be the happy exception.

Alexis de Tocqueville observed that in a democracy, those who vote for taxes often escape the obligation to pay them. He argued that when the poor have the power to make laws, public expenditure tends to be high. This is because taxes are levied in a way that does not burden those who impose them, leading to considerable government spending. Tocqueville also believed that the reliance on government for social improvement could undermine individual responsibility.

Hate being a Debbie Downer but this Country has incrementally moved Left ever since the 1960's and the slide is accelerating as more and more public education indoctrinated kids hit voting age.

We are heading into the same fate as the Roman Empire. Comfort and success leading to comfort and dependence.

And then we let the enemies inside the gates to suck the life and wealth from the diminishing non reproductive natives. The barbarians will suck us dry while we suicidally empathize. They reproduce cockroaches that infest and diminish the culture while preparing to behead us.

And we will feel the warm embrace of AI controlled narratives to distract us from the failed bureaucratic institutions we permitted to enslave us. God help us. We seem incapable of helping ourselves.