From Minneapolis to “Somaliapolis”: How Incentives Reshaped a City

A Case Study in Welfare, Incentives, and Parallel Society

You can subsidize almost anything. You can subsidize work and assimilation, or you can subsidize non-assimilation. Minneapolis shows what happens when a state does the latter and then pretends to be surprised by the result.

Americans are taught a comforting story about immigration.

People arrive, they work, their children learn English, and within a generation or two, they are largely indistinguishable from others except for surnames and holiday recipes. That story was not invented out of thin air. It describes what happened to many immigrant groups who came from countries with functioning states, stable schools, and a basic civic culture, even if those countries were poor.

It is a pattern that depends on what is being imported besides people.

When you import a population from a place where the central state collapsed, where formal schooling was thin for generations, and where survival depended on clan structure and informal law, you do not just import labor. You import a parallel social system. If you then place that system inside a modern American welfare bureaucracy and tell it, in effect, “Here is indefinite support, here are identity protections, and here are political incentives to stay cohesive,” you should not be surprised when you get cohesion without assimilation.

Minneapolis is a particularly useful case study because the Somali diaspora there is large, highly concentrated in certain neighborhoods, politically organized, and now sits at the intersection of multiple public controversies: education strain, welfare utilization, a string of major fraud prosecutions, and bloc-style politics. Minnesota’s Somali population is commonly estimated at tens of thousands, with many sources placing it between 80,000 and 100,000.

The core issue is incentives.

A modern welfare state can subsidize almost anything. It can subsidize work and upward mobility, but it can also subsidize non-assimilation. It can even subsidize fraud if oversight is weak and if political costs attach to asking basic questions. When you combine those forces with an imported clan culture designed to operate as a mini-sovereignty, you get exactly what Minneapolis is now experiencing: parallel institutions, parallel accountability, and a politics that increasingly looks like a transaction rather than a shared civic project.

Cultural Foundations: Diaspora as a Parallel Social System

Start with the structure.

Somali society, especially in its traditional form, is not built around a neutral state with impersonal rules. It is built around kinship. Clan and sub-clan networks serve as insurance, mechanisms for enforcement, and sources of social identity. In a stateless or weak-state environment, that is not “backward.” It is functional. It is how people survive.

The problem is that what is functional in a stateless environment becomes corrosive inside a high-trust, rules-based country.

A modern American city assumes that law is nonnegotiable, that contracts are binding, that the court system is the legitimate forum for settling disputes, and that citizenship entails loyalty to institutions rather than to blood ties.

A clan system assumes the opposite. It assumes that loyalty is personal and inherited. It assumes that disputes are handled internally, preferably by elders or religious authorities, and that shame, honor, and reciprocity serve as enforcement mechanisms. Those are not simply “cultural expressions.” They are governance.

When a concentrated diaspora arrives and remains concentrated, it tends to reconstitute governance. Not necessarily in the form of flags and militias. More often, it appears in the form of informal courts, internal enforcement, social pressure, and economic reciprocity that function as a parallel tax system.

This is where Americans miss what is happening. They see “community.” They see ethnic groceries, language programs, and a neighborhood with a distinct identity. They assume this is the usual immigrant story.

However, something different occurs when the internal social system competes with the state.

You can see the outlines in the kinds of conflicts that repeatedly surface around divorce, domestic disputes, child welfare, and women’s autonomy.

When a community has strong informal authority structures, “the law” is not always the first recourse. Elders, imams, and family networks become the first-line decision makers, and the courts become a last resort, or worse, an outside enemy. That alone changes how a city functions because a legal system cannot work if large pockets treat it as optional.

Then add gender norms.

Somali communities are not unique in having conservative gender expectations, but they often carry a more intense honor framework than the mainstream American norm, and it affects how families interact with institutions. The clash produces predictable consequences: resentment among locals, complex interactions with medical and social services, and bureaucratic incentives to present the household in a manner that maximizes benefit eligibility.

This is not speculation pulled from thin air. It is an institutional reality in any system that allocates resources based on household composition and reported status.

Once you create benefit structures that are sensitive to “single parent” status, you should expect strategic reporting. Once you create political taboos around scrutiny, you should expect less scrutiny. And once you combine that with internal community enforcement that punishes deviation, you end up with legal pluralism even if no law has ever authorized it.

The United States never legislated “pockets of separate law,” but a welfare state can accidentally finance them.

Why Minneapolis Was Not an Accident

One detail often missing from discussions of the Somali diaspora in Minneapolis is the extent to which the concentration became intentional over time. Initial refugee placement explains how people arrived in the United States. It does not explain why they ended up in one state and one metro area in such large numbers.

That explanation lies in secondary migration.

Refugees are free to relocate after initial resettlement, and they do so based on incentives. This is not a cultural peculiarity. It is ordinary human behavior. People move toward places where support systems are stronger, enforcement is lighter, and networks reduce risk.

Minnesota offered all three.

Compared with states such as Texas, Georgia, or Arizona, Minnesota historically maintained more generous access to Medicaid, housing assistance, and social services, along with fewer work requirements and less aggressive fraud enforcement. At the same time, Minneapolis developed a dense nonprofit and advocacy ecosystem explicitly oriented around immigrant and refugee services.

Once a critical mass of Somali households formed, the pull factor intensified. New arrivals did not face the isolation that often forces rapid assimilation. They arrived into a functioning parallel infrastructure: landlords familiar with benefit programs, employers recruiting within the community, mosques that doubled as social hubs, and advocacy organizations that specialized in navigating bureaucracy.

Secondary migration turned humanitarian resettlement into demographic concentration. Concentration then produced political leverage, which further protected the system that attracted more migration in the first place.

This feedback loop matters because it shows that Minneapolis is not merely a passive recipient of history. It illustrates how policy choices shape population flows, even when those choices are framed as moral imperatives rather than incentives.

Cognitive: Development and Education Deficits

The second piece is the least discussed, which is why it matters.

America is a high-literacy civilization. Our economy assumes abstract reasoning, bureaucratic competence, time discipline, future planning, and the ability to learn new systems quickly. Even “low-skill” work now often requires navigating forms, compliance requirements, schedules, and multi-step processes.

If you come from a country where schooling was interrupted for generations, where literacy rates were low, where learning often meant rote memorization and deference to authority, and where daily life did not require the cognitive habits of a post-industrial economy, you arrive at a serious disadvantage.

That disadvantage is not a moral failing. It is a human fact. But policy cannot pretend facts are insults.

Refugee resettlement does not magically rewrite the past. It relocates people. It does not instantly create the deep literacy and cognitive toolkit that modern economies reward.

This is where Minneapolis schools come in.

Minneapolis Public Schools is not operating on the national average. It is operating under unusually heavy needs, and the numbers show how much money is flowing through the system.

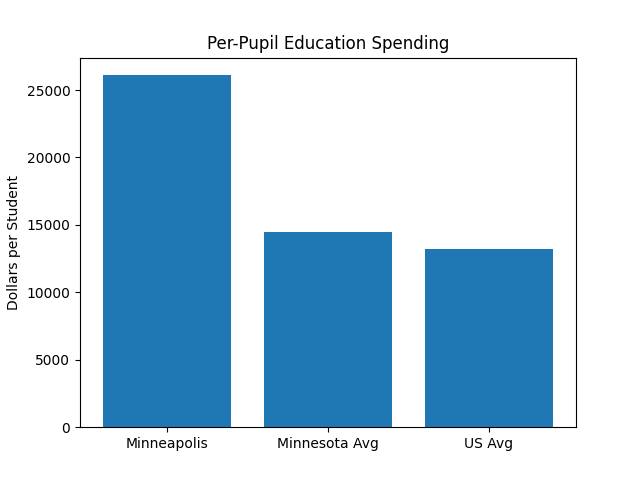

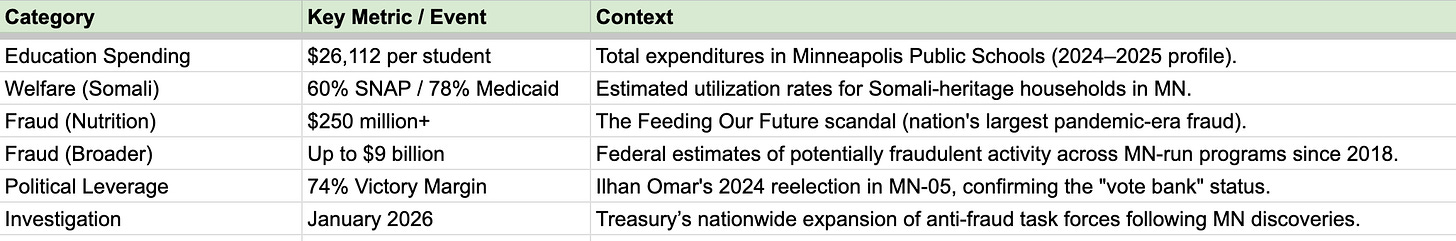

According to NCES district fiscal data (from 2021–2022, displayed on the district’s 2024–2025 profile), Minneapolis Public Schools had total expenditures of about $26,112 per student and current expenditures of about $21,154 per student. That is not a small figure. This indicates that the system is handling a substantial load of services beyond basic instruction.

What often goes unsaid is that this spending is not abstract. It is zero-sum. Every dollar devoted to remediation, translation, and crisis management is a dollar not available for advanced coursework, vocational training, facility upgrades, or enrichment programs for the broader student population. When resources are finite, priorities are revealed by outcomes. Minneapolis has not simply chosen to spend more on education. It has implicitly chosen to redirect large portions of its education budget toward permanent catch-up rather than broad advancement. That tradeoff has consequences, even if no one ever votes on it explicitly.

Now focus on language and remediation.

English learners impose real costs: extra staff, smaller group instruction, translation capacity, and often special education crossover issues. Nationally, English learners were about 10.6% of public school students in fall 2021. In some Minneapolis schools, the share is far higher. One example, Andersen United Middle School in Minneapolis, was reported as 37% English learners early in the school year, with many languages spoken.

A school can do heroic work under those conditions, but “heroic” is not a funding model. If a district is asked to function as both a school system and a permanent catch-up academy for large numbers of students arriving with major deficits, the system’s mission changes. It becomes a social-service agency with textbooks.

And here is the point that makes people uncomfortable: the gap often does not close quickly. Not because teachers are bad, and not because students are incapable, but because cognitive development and literacy are cumulative. You cannot compress ten years of stable schooling into eighteen months of ESL support.

So the public pays twice. First through the education budget, and then again through the welfare budget when school-to-work transitions fail.

This is the “cognitively unarmed” problem. People learn to fill out forms and repeat the expected phrases, but they do not necessarily gain an internalized understanding of what the forms mean. Bureaucracies that are designed for rule-following are vulnerable to box-checking.

When a welfare system is large, complex, and politically protected, the people best positioned to thrive are not always the people who work hardest. Often it is the people who learn the rules fastest, or the people who learn the loopholes.

Why Education Spending Alone Cannot Close the Gap

Public discussion often treats education as the master solution. If outcomes are poor, the assumption is that schools need more money, better training, or more time. Minneapolis shows the limits of that belief.

The city already spends heavily. As noted earlier, per-student expenditures exceed national averages by a wide margin. Yet large gaps persist, not because schools are negligent, but because schools are being asked to compensate for developmental deficits that predate arrival.

Literacy is not merely the ability to decode words. It is the ability to reason abstractly, follow multi-step instructions, and operate comfortably inside rule-based systems. These habits develop early and accumulate over time. They are reinforced by parents who themselves are literate, by homes filled with books, and by social environments that reward delayed gratification.

ESL instruction addresses language barriers. It does not recreate those early conditions.

This distinction matters because policymakers often conflate the two. When test scores or graduation rates fail to converge, the response is to increase spending or lower standards. Neither addresses the underlying mismatch.

The result is credential inflation. Diplomas signal less. When that signaling power erodes, employers respond rationally by raising informal hiring thresholds, relying more on personal networks, referrals, or elite private credentials, which further disadvantages anyone trying to break out of an enclave without those connections. Employers compensate by raising informal hiring thresholds. Young adults cycle through low-wage work and public assistance. Welfare becomes a permanent supplement rather than a temporary bridge.

This is not an indictment of students or teachers. It is a reminder that institutions have limits. Pretending otherwise does not help the people caught inside the system.

Socio-Economic: Clan Economy Meets Welfare State

Now combine the cultural system with the welfare bureaucracy.

Somali culture, like many clan-based cultures, strongly valorizes redistribution within kin networks. The expectation is that success is shared. Money is not merely personal property. It is a resource that binds the group together.

Again, in a harsh environment without a stable state, that makes sense. In America, that instinct does something interesting when paired with public assistance: government transfers become the new tribal dues.

If a household receives benefits, that income can be redistributed through the network in the same way support would have been distributed through the clan. It is not unusual for remittances to be sent abroad or for resources to circulate through extended family structures. What changes is that the source is no longer productive output. It is the taxpayer.

From a fiscal perspective, this also represents a leakage of domestic stimulus, as funds intended to circulate through the Minneapolis economy instead flow abroad, reducing the local multiplier effect that public spending is expected to generate.

So the question is not, “Do they share?” The question is, “Who is funding the sharing?”

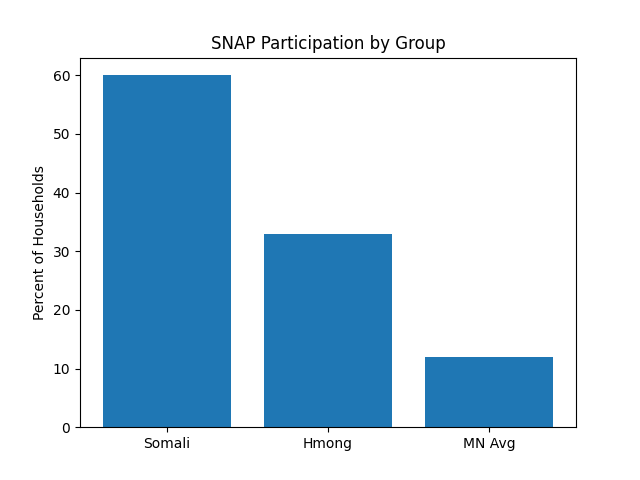

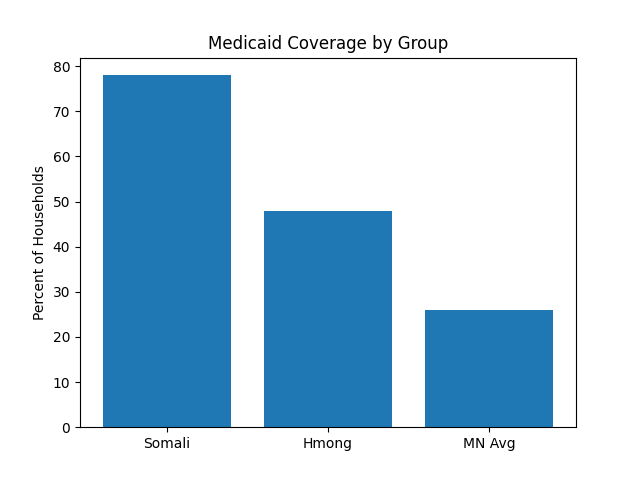

This is where the welfare utilization data matters.

A widely cited set of Census-based estimates reported that among Minnesotans reporting Somali ancestry, about 60% reported receiving SNAP in the prior 12 months and about 78% reported having Medicaid as their health insurance (with especially high Medicaid coverage among Somali children).

Even if you debate the precise percentages, the broad point is not in dispute: public assistance utilization is high, and it is persistent.

High utilization by itself does not prove fraud. It does not prove ill will. It proves dependency. And dependency becomes a trap when it is combined with low labor-market integration.

A useful comparison exists in the same metropolitan area. The Hmong refugee population in St. Paul arrived under similarly traumatic circumstances and with limited initial resources. Yet over time, Hmong households have shown higher labor-force participation, greater small-business formation, and lower long-term reliance on public assistance relative to the Somali population. This is not because the Hmong were treated differently by the state. It is because family structure, educational expectations, and attitudes toward work and self-reliance differed. The comparison matters because it isolates variables. When two refugee groups operate under the same welfare regime but produce different outcomes, culture and incentives cannot be dismissed as irrelevant.

The next step is gray-zone exploitation.

Whenever you build a large benefits system, you create opportunities for three behaviors:

honest need,

strategic optimization,

outright fraud.

The first is legitimate. The second is predictable. The third is criminal.

Minneapolis and Minnesota have been hit with major fraud prosecutions that show what happens when oversight is weak and incentives are strong.

The most infamous is the Feeding Our Future scandal, which federal prosecutors described as the nation’s largest pandemic-era fraud scheme in the child-nutrition sector. The case centered on federal funds intended to feed children during COVID, routed through a state-administered program, with claims of hundreds of millions in fraudulent reimbursements.

By late 2025, reports and official statements indicated dozens of convictions in the Feeding Our Future case, with ongoing prosecutions and significant difficulty in recovering funds.

And it did not stop there.

Federal and state authorities also pursued cases tied to Minnesota programs, such as Housing Stabilization Services and autism-related services billed through Medicaid, that described large-scale schemes involving billing for services not provided, kickbacks, and rapid provider growth that should have triggered alarms.

One Associated Press report summarized the federal concern bluntly: investigators were examining whether up to half of roughly $18 billion in federal funds across a set of Minnesota-run programs since 2018 may have been stolen through fraud.

That figure is staggering. Even if later audits revise it down, it tells you what federal investigators believed they were seeing.

Now connect that back to social structure.

Fraud at scale is not typically the work of isolated individuals. It requires networks: recruiting clients, creating plausible paperwork, coordinating multiple entities, and maintaining silence. A tight-knit community with strong internal loyalty and high reciprocity is, structurally, more capable of coordinated behavior, including coordinated wrongdoing, than a population of atomized individuals who barely know their neighbors.

That does not mean the community is inherently criminal. This indicates that the community is highly organized.

In a high-trust, low-oversight benefits environment, organization becomes power.

Minneapolis becomes the place where this collision is visible because it is where money, concentration, and political protection meet.

Political Alignment: Dependency as Strategy

At this stage, the story turns political because it cannot avoid politics.

Welfare systems are not merely administrative. They are political ecosystems. Whoever controls the ecosystem controls jobs, contracts, grants, and the flow of money.

Once a community becomes heavily dependent on government programs, it becomes rational for that community to align with the party that is least likely to question those programs.

In practice, that means alignment with the Democrat Party, which has built a modern coalition around identity politics, expansive social spending, and moral intimidation as a substitute for argument.

Minneapolis is a textbook example of what happens when bloc voting and identity politics merge.

Ilhan Omar’s congressional district is deep blue, and she has won by large margins. By the mid-2020s, Ilhan Omar’s district had become electorally noncompetitive, with her 2024 reelection by roughly 74% serving as confirmation rather than surprise. Minnesota’s official election results show that in 2024, she won MN-05 with roughly 74% of the vote. Sahan Journal similarly reported that she won easily in 2024.

But the more important point is not a single election margin. It is the development of an “ethnic vote bank” logic where political loyalty is exchanged for protection, funding, and institutional deference.

That deference shows up in the way oversight becomes radioactive.

If investigators or journalists ask basic questions about program spending, they risk being accused of racism or “Islamophobia.” If state agencies tighten controls, they risk being painted as targeting a minority community. Those accusations do not need to be true to be effective. They simply need to raise the cost of enforcement.

You can see this dynamic explicitly in commentary around the Feeding Our Future case, where race-based accusations were part of the public narrative around oversight and enforcement.

As the money flows deepen, a middle layer forms around them: nonprofits, community organizations, advocacy groups, and contractors whose livelihoods depend on the continuation of the funding stream.

This is where “NGO funding flows” matter.

The typical pipeline looks like this:

Federal money is authorized for a program.

A state agency administers it and remits payments to providers.

Providers, often nonprofits or newly formed “services” businesses, bill the program.

Local political actors and advocacy organizations defend the system, often framing scrutiny as bigotry.

A portion of the money becomes salaries, consulting fees, and contracts that build a permanent constituency for expansion.

Once that structure exists, reform becomes politically untouchable. You are no longer debating policy. You are threatening livelihoods.

This is why Minneapolis, and Minnesota more broadly, has become a national symbol in recent years: federal authorities and multiple media outlets have reported widespread concern that fraud and weak oversight have become systemic.

Even if you strip away every partisan interpretation, one fact remains: when a system can be looted at scale, it will be looted at scale. The only real question is how quickly you close the doors and whether you are allowed to close them without being morally blackmailed.

Moral Intimidation as a Substitute for Oversight

One of the most important forces sustaining these patterns is not money, but fear.

In theory, public programs are overseen by auditors, inspectors, and administrators charged with enforcing rules impartially. In practice, enforcement is filtered through the lens of political risk. That risk is not evenly distributed.

In Minnesota, as in many progressive jurisdictions, enforcement involving minority communities carries reputational danger. Questions about fraud or misuse are readily reframed as expressions of racial hostility. Administrators learn quickly that approving claims is safer than challenging them.

This creates moral hazard.

Once enforcement becomes politically risky, bad actors do not need to evade detection. They only need to raise the cost of detection. Accusations of racism or Islamophobia do that effectively, regardless of their truth.

The Feeding Our Future case illustrated this dynamic clearly. Oversight concerns were raised early. Red flags appeared. Yet the system continued to approve payments until federal prosecutors intervened.

This pattern is not unique to Minnesota, but the state provides one of the clearest examples of how moral intimidation can supplant institutional discipline. When that happens, public programs become vulnerable not because people are evil, but because the system rewards silence.

Consequences for the United States

This is where the broader American stakes become clear.

Fiscal consequences

Minneapolis is not simply paying for services. It is paying for an entire parallel infrastructure: expanded school staffing, expanded social services, translation capacity, healthcare utilization, housing supports, and then the downstream costs of unemployment, low earnings, and intergenerational dependence.

On top of that, Minnesota has faced repeated large-scale fraud cases tied to public programs, with federal investigators describing “industrial-scale” fraud concerns.

Taxpayers do not merely lose money. They lose trust. Once citizens believe the system is rigged, they stop supporting the system, including the parts that genuinely help the vulnerable.

Cultural consequences

A multicultural society can work when assimilation is real. Assimilation does not mean erasing your past. It means you adopt the civic rules of your new home and treat them as superior to clan loyalty.

Parallel communities do the opposite. They replicate the governance norms Americans thought they had moved beyond: informal justice, clan patronage, fatalism, and in some cases severe gender control.

A city that permits this does not become “diverse.” It becomes fragmented.

Political consequences

The precedent is dangerous: any group large enough and concentrated enough can bargain its way out of assimilation by turning itself into a protected voting bloc.

That turns citizenship from a shared idea into a transaction. It changes the meaning of “American” from a commitment to principles into a negotiation over benefits.

Psychological consequences

Finally, there is the quiet corrosion that happens in ordinary minds.

If you are an average working person, paying taxes, obeying laws, and trying to live decently, and you watch a system where rules are enforced unevenly, where scrutiny is silenced by accusations, and where public money can be siphoned through programs that were supposed to help the vulnerable, you learn a lesson.

You learn that virtue is optional if you have the right identity shield.

You learn that honesty is for suckers.

You learn that citizenship is not a duty; it is a claim.

And once enough people learn that lesson, the republic does not collapse with a bang. It collapses with a shrug.

Why Minneapolis Matters Nationally

It would be comforting to treat Minneapolis as an outlier. It is not.

The same incentive structures exist wherever generous benefits, weak enforcement, and identity-driven politics intersect. The difference is in degree, not kind.

Federal programs are national. Oversight is often delegated to states. Advocacy networks share strategies across cities. When one jurisdiction demonstrates that accusations of bigotry can neutralize enforcement, others learn the lesson.

Minneapolis shows the end state of a process that begins quietly. Parallel institutions do not appear overnight. They emerge gradually, normalized by good intentions and protected by moral rhetoric. By the time scandals break, the ecosystem is already entrenched.

This is why the unlocked door metaphor matters.

The Somali diaspora did not create Minnesota’s vulnerabilities. It revealed them. Any sufficiently organized group placed inside a generous, weakly enforced system will behave similarly. That is not a cultural judgment. It is an institutional one.

When Equal Rules Become Optional

The Somali diaspora in Minneapolis did not “cause” every weakness in Minnesota’s welfare state, just as a burglar did not “cause” a homeowner to leave the door unlocked. However, a burglar reveals that the door was unlocked.

What Minneapolis is showing the country is not merely an immigration problem. It is a governance problem. It is what happens when a modern state tries to import a parallel society and then finances its permanence through bureaucracies that are too timid, too politicized, or too compromised to enforce their own rules.

You can have compassion without surrendering your system.

But you cannot keep your system if you keep rewarding surrender.

Help Keep This Work Alive

If you made it this far, you already understand something many people prefer not to think about.

What’s happening in cities like Minneapolis is not an accident, and it’s not going to fix itself. It continues because too few people are willing to say plainly what incentives reward and what institutions tolerate.

That kind of writing does not get sponsored. It does not get grants. And it does not get protected.

It survives only if readers who find value in it decide that it’s worth supporting.

Become a Paid Subscriber

A paid subscription is the simplest way to support this work and keep it going.

Paid subscribers make it possible for me to keep writing long-form, evidence-based essays like this one without watering them down or chasing outrage for clicks.

If this essay clarified something for you, challenged a comfortable assumption, or gave you language to describe what you already sensed was happening, a paid subscription is how you help ensure there is more of it.

Make a One-Time Gift

If a subscription doesn’t make sense for you right now, one-time contributions help more than you might think.

They cover immediate costs. They buy time. And they signal that this work has real value beyond passive agreement.

Join The Resistance Core

For readers who want to do more than keep the lights on, The Resistance Core is the top-tier option.

Members directly underwrite investigative projects, long-form research, and essays that take weeks rather than hours to produce. This is where the most ambitious work becomes possible.

What Your Support Builds Right Now

Your support is not abstract.

It pays for:

Time to research and write pieces like this properly

Keeping me focused solely on writing

The ability to publish without worrying about appeasing sponsors or platforms

In short, it buys independence.

If You Cannot Give

If money is tight, sharing this essay helps more than you may realize.

Send it to someone who still believes incentives don’t matter. Post it where it will reach readers who don’t already agree with you. Quietly expanding the audience matters.

Great article. Multiply Minnesota by 50 and the scale of the problem becomes clearer.

We used to have an American culture, an American "story", that most of us bought into and expected immigrants to adopt in order to assimilate. That doesn't exist anymore. I believe we've reached a critical mass of natural born Americans who are either wholly ignorant of our history and founding principles or they actually reject them. There are generations of American kids who've been taught the Howard Zinn/1619 Project version of American history who then grew up to be voters who loathe their own Country. There's just no pressure put on immigrant groups like Somalis to adopt OUR culture rather, the pressure is on us to adopt THEIR culture. One wonders why it is they immigrated here in the first place if they wanted to keep their old way of life. Oh yeah, there is our easily scammed cradle to grave welfare state. You know, the one immigrants as a condition of their immigration are supposed to be ineligible for?

There's actual talk about making certain areas in cities "no go zones", autonomous, immigrant controlled areas governed by their own laws. Hell, the Muslim mayor of Dearborn MI tried to add Arabic writing to the police department insignia and told a Christian political opponent to leave the city because "he's not wanted" there. The Left is using mass immigration to change the demographics and politics of States and cities and there's no significant or effective pushback. As Minnesota and Minneapolis show, they're winning.

Also, we're living in a kleptocracy now. Government (at all levels) has grown so huge and the sums of money flowing into government coffers is so vast, accountability is impossible and the incentive for graft and corruption is great. Then, couple that with an immigration system that is untethered from the laws meant to regulate it and you have a recipe leading us towards national suicide.

I really hate to be a Debbie Downer but it seems like we've reached that point in the life of a Republic where a critical mass of the citizenry is either too ignorant or too morally corrupt to sustain it.

Another excellent piece. It's funny how just plain stating the obvious or explaining that which becomes obvious has become such a political liability. Of course people respond to incentives. Of course the US is a high-trust society that doesn't fare well when people don't play by the rules. We need to realize that some cultures will not play but the rules that this country runs on, and plan accordingly. I hope that all who are here can find ways to live peacefully and productively.