How Nations Fail: The Immigration Lie

A Government That Won’t Protect Its Borders Won’t Protect Its People

Immigration did not break America. What broke America was the lie that it could absorb endless inflow without limits or expectations.

The America We Remember

A nation does not usually recognize the moment when it begins drifting away from the assumptions that once held it together. The United States of 1965 was far from perfect, but it was still a country that understood itself. Its population was about 194 million. Roughly nine million were foreign-born, which meant immigration was a visible part of American life, but not a dominating force. Schools functioned on the assumption that most children spoke English. Neighborhoods in many cities still held a mixture of working and middle-class residents who had stable employment in an economy where a single income could often support a household.

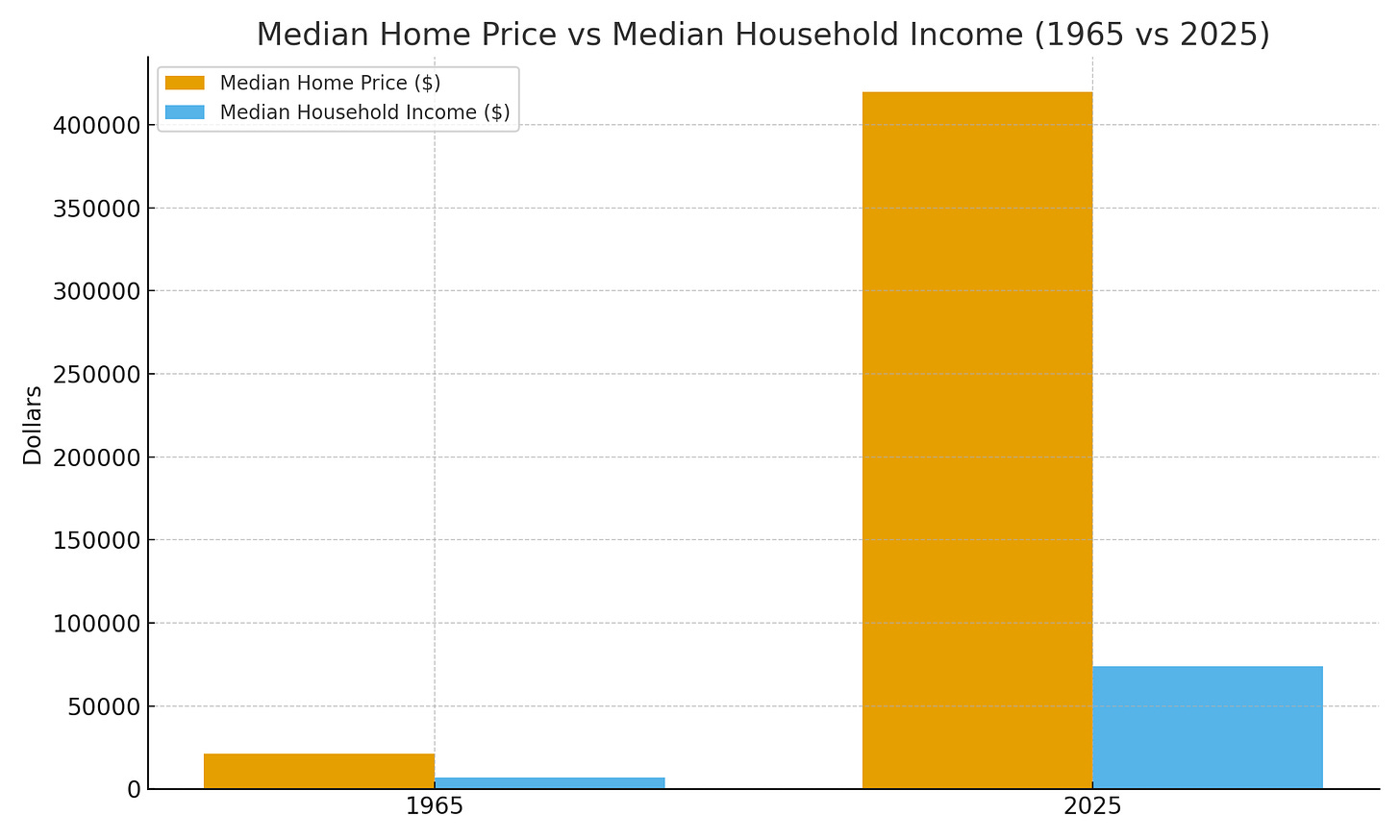

A manufacturing worker in the early 1960s, earning the equivalent of perhaps sixty to seventy thousand dollars in today’s money, could buy a modest home without needing two full-time incomes. The price of a typical house was about three years of median income, not eight or nine. Work, savings, and discipline could realistically move a family upward. The federal government provided welfare programs long before 1965, but these programs were smaller and narrower in scope than those that would come later. They did not define the everyday life of entire neighborhoods.

Cultural unity was never complete in a country as large as the United States, yet there were enough shared references that a person from Boston could speak to someone from Denver or Atlanta and find common understandings. The national story was taught with a sense of pride. Schools assumed a duty to transmit the country’s core principles, sometimes too simply and sometimes too confidently, but with a clear intention. Citizenship was something that had meaning beyond paperwork.

Immigration fit into that world as a process rather than a slogan. The expectation was straightforward. The door opened for those who met certain requirements, and those who came were expected to become American. English was not treated as negotiable. Newspapers, civic groups, and churches offered help to newcomers, but the help pointed toward joining the mainstream, not remaining separate. This was not hostility. It was clarity. A nation cannot be held together if it tells newcomers that belonging is optional.

This context matters because the decisions made after 1965 did not land in a vacuum. They landed in a country that assumed assimilation would continue automatically, even as the policies that sustained assimilation were being quietly removed. They landed in a society whose institutions were not designed for large-scale demographic shifts. And they landed in a political climate where trust in federal problem-solving was rising faster than the federal government’s ability to deliver.

The fractures of the late twentieth century did not begin with hatred. They began with confidence. Lawmakers assumed the country was strong enough to absorb major changes without preparing for the consequences. That confidence turned out to be misplaced.

The Great Opening: 1965 and What Followed

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, often called the Hart-Celler Act, has been one of the most consequential domestic laws with the least public understanding. It eliminated the national-origin quotas that had governed immigration since the 1920s. Supporters said the old system was unfair and outdated. They also promised that the new approach would not significantly change the country’s demographic balance.

Senator Ted Kennedy, who championed the bill, insisted that it would not flood American cities with immigrants and that the ethnic mix of the country would remain largely unchanged. At the time, immigration levels were modest and the quota system seemed like a relic. Few voters imagined that the replacement would function very differently from what they had known.

The new system put family ties at the center. That sounded humane, but it changed the arithmetic. Each new immigrant could sponsor a spouse and minor children, who could later sponsor their own relatives. The effect was to create a chain migration mechanism. For every one person admitted under earlier rules, the new system could eventually generate multiple additional family-based admissions, regardless of domestic labor demand or institutional capacity.

Legal immigration rose sharply within a decade. By the mid-1970s, annual inflows exceeded 400,000. By 1980, they were above 800,000. Families brought spouses, children, and extended relatives. The law worked exactly as written, though not as many sponsors had predicted when they reassured the public.

At the same time, the United States was expanding Great Society programs created under President Lyndon Johnson. Medicaid, federal housing assistance, food programs, and education grants grew in reach and budget. These programs had been designed primarily around the needs of citizens, yet by the late 1970s and 1980s they also supported large numbers of recent immigrants, both legal and illegal. The combination of increased inflow and expanded welfare created a web of incentives. Families arriving with limited English and limited financial resources naturally relied on public systems. The more those systems grew, the easier it became to argue for even greater spending.

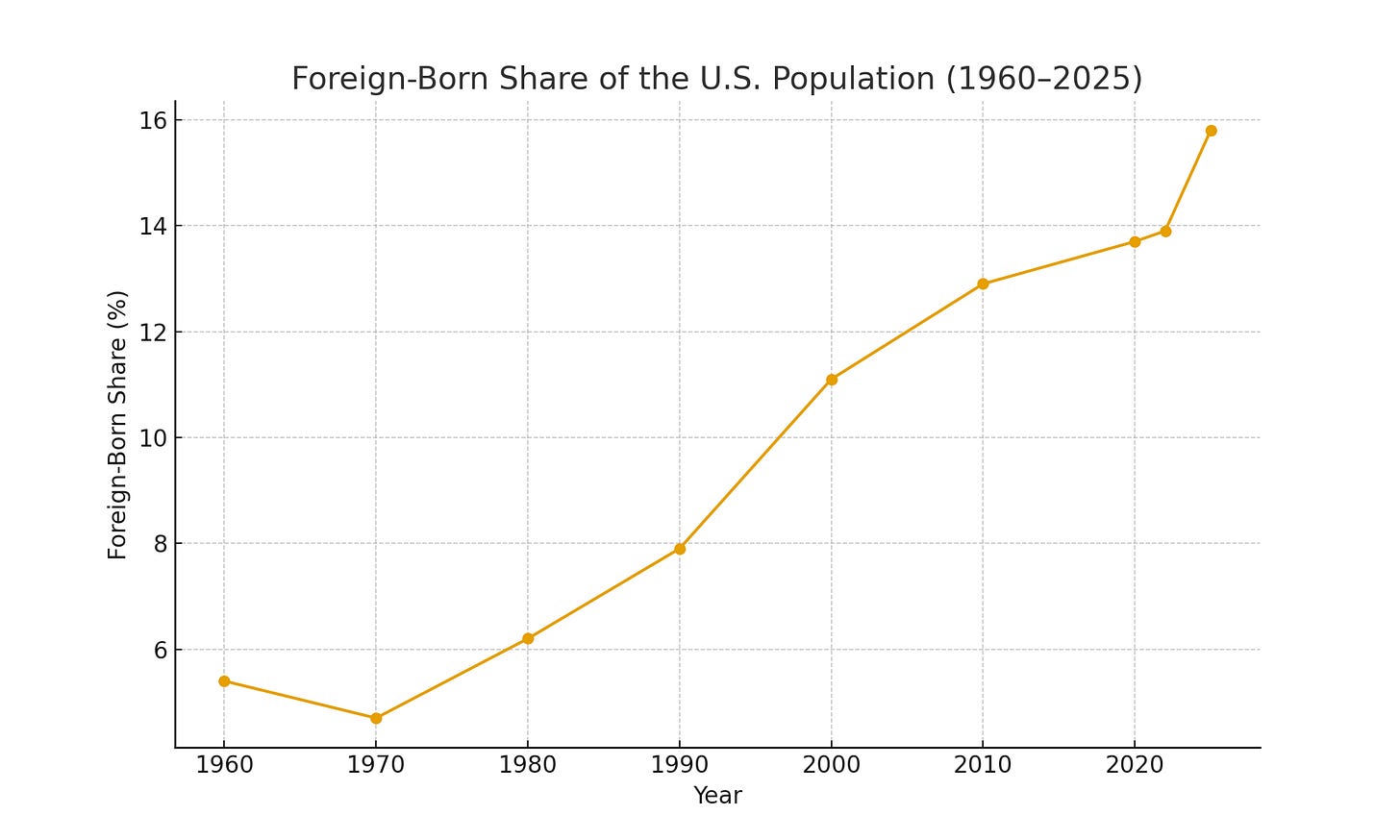

Demographic changes followed in a predictable fashion. The population rose from about 194 million in 1965 to somewhere around 330 to 335 million by 2025. A significant portion of this growth came from immigrants and the U.S. born children of immigrants. The foreign-born share of the population rose from about five percent to more than fourteen percent, one of the highest levels in American history. Before 1965, most immigrants came from Europe. After 1965, the majority came from Latin America and Asia.

None of this means immigration is inherently harmful. It means scale matters. Systems designed for modest inflows do not automatically function when inflows become large and continuous. Public schools, housing markets, labor markets, and civic traditions all have carrying capacities. A country can grow and often benefits from growth, but that growth must be matched by the ability to integrate those who arrive.

The political incentives shifted as well. The Democrat Party increasingly framed immigration in moral terms rather than practical ones. Restriction was portrayed as backward or unjust, while expansion was treated as proof of national compassion. These arguments were emotionally powerful but often disconnected from what cities, schools, and working-class neighborhoods were experiencing. Meanwhile, businesses favored higher immigration for reasons having little to do with morality. A larger labor pool tends to hold wages down, especially in low-skill sectors. Moral rhetoric and economic self-interest pulled in the same direction. Confronting the structural consequences of perpetual inflow became politically costly.

By the time the country began to recognize the scale of the change, the new system was deeply rooted. Immigration was no longer a controlled process. It had become a permanent condition.

Why the Inflow Never Slowed

Immigration policy is often discussed as if it were driven by lofty principles. In reality, it follows incentives like any other policy. After 1965, a series of legislative decisions, administrative actions, and court rulings created an immigration system that tends to expand by default. It expands because the institutions involved benefit from expansion and feel relatively little pressure when the system strains.

The Refugee Act of 1980 was an early turning point. It standardized refugee admissions and gave presidents wide latitude to set annual ceilings. The law responded to genuine crises, especially in Southeast Asia, and was sold as a humane framework. It also allowed refugee numbers to climb without repeated congressional votes. A network of private resettlement agencies grew alongside these admissions. These agencies contracted with the federal government to place refugees across the country. More arrivals meant more contracts, staff, and influence.

The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, known as IRCA, was another milestone. It granted legal status to nearly three million people living illegally in the United States. The promise was that legalization would be paired with strong workplace enforcement to deter future illegal entry. Legalization arrived quickly. Enforcement did not. Employer sanctions faced resistance from advocacy groups and businesses, and court challenges narrowed their scope. Political will to sustain audits and penalties was weak. As a result, illegal entry continued. The larger lesson for potential migrants was clear. If one could remain long enough, legalization might eventually arrive.

The Immigration Act of 1990 expanded legal immigration further. It raised visa ceilings, created new employment-based categories, and added the diversity visa lottery. Supporters marketed the law as modern and flexible. In practice, it increased inflow and deepened complexity. Immigration lawyers prospered. Universities and large employers benefited from easier access to foreign students and workers. Families brought more relatives. The bureaucracy grew.

In the 1990s and 2000s, many cities and some states adopted sanctuary policies limiting cooperation with federal immigration authorities. These policies were justified in civil rights language, but they fragmented enforcement. A person encountered by local police in one jurisdiction might be reported to federal authorities; the same person in another jurisdiction might not. These inconsistent consequences shaped behavior long before Congress debated any change.

In 2012, the federal government created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. DACA granted temporary protection and work authorization to certain people brought to the country illegally as minors. For those already present, it provided relief from uncertainty. For those considering migration, it created a precedent. Illegal entry could eventually lead to a recognized status category even without congressional action. Many later arrivals cited this expectation when explaining their decisions.

The result of these developments was not a master plan, but a pattern. Refugee agencies benefited from higher numbers. Businesses benefited from lower labor costs. Universities benefited from foreign tuition. Advocacy groups benefited from larger potential constituencies. The Democrat Party benefited politically from populations that tended, on average, to support redistributive policies. Federal and local bureaucracies benefited from larger caseloads and budgets.

Immigration did not become difficult to manage because no one knew how to enforce laws. It became difficult because too many institutions learned how to benefit from not enforcing them.

Assimilation: The Expectation That Quietly Disappeared

The success of earlier immigration waves depended on a simple arrangement. The country opened its doors under certain conditions. Those who entered were expected to join the existing civic culture. That expectation turned diversity into something manageable. It directed different groups into a common life rather than multiple separate lives.

In the decades after 1965, this arrangement weakened. The change did not come from immigrants insisting on separateness. It came from policymakers and educators redefining what fairness and identity required.

Court rulings in the 1970s interpreted equal protection principles to require meaningful instruction for non-English speaking students. This was reasonable in principle. In practice, it led to the widespread adoption of bilingual education models that kept students in separate tracks for many years. Instead of teaching English as rapidly as possible, some districts created parallel systems in which progress into mainstream classes slowed. Federal funding formulas paid schools based on the number of students classified as English learners. That created a subtle incentive to maintain those classifications.

By the late 1990s, English learner enrollment had climbed into the millions. By 2025, roughly five million students in public schools fall into this category. Large districts in states such as California, Texas, Florida, and New York teach in numerous languages. Some students acquire English quickly and exit the programs. Many do not.

At the same time, multiculturalism replaced the older idea of the melting pot in teacher training and curriculum design. University education departments recast assimilation as suspect. The new emphasis was on affirming every culture rather than asking students to join a common civic culture. Public agencies began producing materials in dozens of languages as a presumed sign of respect. In practice, this made it increasingly possible for people to navigate daily life without learning English.

The same Democrats who chant “nation of immigrants” are the ones who quietly dropped the second half of the idea: the melting pot.

Surveys of immigrants consistently show that most understand the importance of English and want to learn it. The barrier is less willingness than policy. When a society stops insisting on assimilation, assimilation slows. A confident society can extend help while expecting newcomers to adopt its language and norms. A hesitant society confuses expectations with hostility and abandons them.

Civic consequences followed. In earlier eras, immigrant mutual-aid societies and civic clubs taught new arrivals how to function in American institutions. Over time, ethnic advocacy organizations took on a different role, often emphasizing group-specific grievances and demands. Instead of integrating into a shared story, communities were encouraged to view themselves primarily through the lens of distinct identity and collective victimhood.

Assimilation did not vanish because immigrants refused it. It eroded because the people responsible for shaping institutions stopped valuing it.

Everyday Consequences for Working Americans

Much of the public debate about immigration uses national aggregates such as gross domestic product. These figures can be misleading because they describe the total pie without describing how it is divided or what it feels like to live within the system.

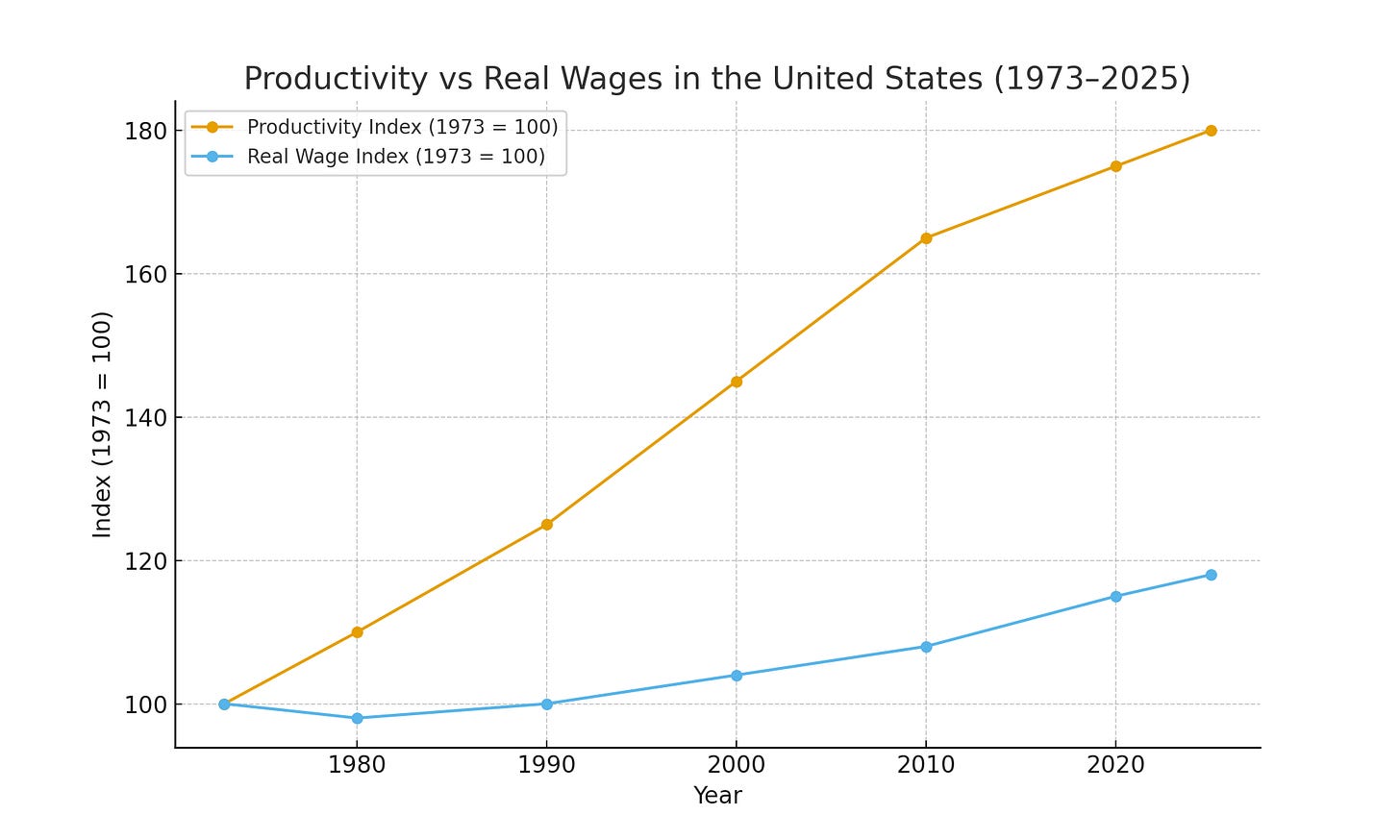

Since the early 1970s, labor productivity in the United States has nearly doubled. Output per worker has risen dramatically. Median real wages for many workers have not kept pace. Economists debate the size of immigration’s role in this divergence, but there is little doubt that expanding the supply of low-skill labor exerts downward pressure on wages for the native born with similar skills. This is most visible in construction, food service, agriculture, hospitality, and certain manufacturing sectors.

Housing has followed a different but related path. Population growth, driven by immigration and longer lifespans, has pressed against tight housing supply in many regions. Zoning rules restrict new construction in established neighborhoods. Environmental review processes and litigation can delay projects for years. The result is a housing shortage that drives up rents and home prices. In the mid-1960s, a typical household could purchase a home with about three years of income. By the mid-2020s, that ratio often exceeds eight in many metropolitan areas.

Working families experience this as a squeeze. Higher rents and higher home prices consume a greater share of income. Childcare costs, also influenced by labor markets and regulation, add another claim. The practical result is that two full-time incomes are now often required to achieve the same stability that one income provided half a century earlier in many parts of the country.

Public services absorb strain as well. Schools teach students speaking many different languages, from many different backgrounds, often with widely varying levels of prior schooling. That reality requires more staff, specialized training, and programs aimed at language and acculturation. Those programs cost money and time. Gifted education and deep remediation for native-born students can suffer as resources are diverted toward managing language and integration challenges.

Hospitals in high-intake areas treat more uninsured and underinsured patients. Emergency rooms, which are legally required to provide stabilizing care, become a point of first contact for people who cannot navigate the system in English or who fear interaction with official institutions. This increases wait times and cost burdens.

These costs do not fall evenly. Wealthier citizens can shield themselves from many of these pressures by moving to low-immigration areas, using private schools, or relying on private healthcare. Poor and working class communities absorb the daily reality of crowded classrooms, overused facilities, and increased competition for housing and jobs. For them, immigration policy is not an abstraction. It is one more factor in a life lived with thin margins.

None of this indicts immigrants as individuals. Many work hard and contribute significantly. The point is that systems have limits, and when inflows exceed those limits, someone pays. In the American case, the people who pay most are those with the least leverage over the policies that created the situation.

The Immigration Industry

A country can make a mistake once. It becomes dangerous only when the mistake becomes an industry. Modern immigration is no longer simply a flow of people across a border. It is an ecosystem of agencies, nonprofits, lobbying groups, contractors, and political interests whose incentives grow as the inflow grows.

This dynamic did not begin at the border. It began in Washington.

The 1965 Act set the chain migration mechanism in motion. The 1980 Refugee Act created a permanent pipeline for resettlement agencies. The 1986 amnesty created precedent for legalization even when enforcement failed. The 1990 Act expanded visa categories and built a legal maze that required lawyers, consultants, and universities to manage. Each of these laws was sold as humane modernization. Each one also created constituencies that benefited financially or politically from higher numbers.

Refugee resettlement agencies grew into federally funded contractors. Universities recruited foreign students at full tuition. Corporations in agriculture, construction, hospitality, and tech lobbied for more visas to suppress labor costs. Ethnic advocacy organizations grew in influence as their potential membership expanded. The Democrat Party increasingly relied on these populations as part of its electoral coalition, calling the stance “compassion” while treating demographic change as a strategic advantage. The bureaucracies inside DHS, the courts, and state agencies expanded their budgets and staff as caseloads rose. No one inside the system benefits from fewer cases.

By the 2010s and early 2020s, an entire nonprofit and consulting economy existed to manage the consequences of policies that were never designed with limits in mind. During the surges between 2021 and 2024, cities like New York and Chicago found themselves dependent on the same NGOs whose funding grew as the crisis grew. The worse the strain became, the more contracts were issued. This is an incentive structure that guarantees permanence. It rewards handling the consequences of failure, not preventing failure.

These actors are not conspiring. They are responding to incentives. When government money flows to programs that expand with need, the system will quietly prefer need. When political parties gain voters from inflow, they will frame enforcement as immoral. When businesses profit from loosened borders, they will speak of “labor shortages.” When advocacy groups gain relevance from demographic change, they will define assimilation as oppressive. Every component of the immigration industry is fed by continued inflow.

And because so many livelihoods now depend on immigration as a permanent condition, there is no natural pressure inside the system to ask whether the country itself is benefiting.

This incentive structure is the quiet engine behind America’s immigration confusion. Policy is no longer shaped by what the nation can responsibly absorb. It is shaped by what the immigration industry can continue to manage. The result is a system that expands automatically, even when national cohesion weakens.

How Other Countries Handle Immigration

Immigration debates in the United States often sound unique, as if other nations never wrestle with similar issues. In fact, nearly every developed country has been forced to confront fundamental questions about numbers, capacity, and integration. The difference is that most of them treat the matter as technical rather than existential.

Japan admits relatively few permanent immigrants each year, despite having one of the oldest populations in the world. Long-term residence is tied to income, conduct, and language ability. Naturalization usually requires renouncing former citizenship. The policy may be criticized as too strict, but it reflects a belief that social cohesion is an asset that cannot be taken for granted.

Japan’s Hispanic population is estimated at well under 20,000 people in a nation of 125 million, and Japan does not restructure its language or institutions around them.

South Korea links long-term residence to language proficiency, civics knowledge, and economic stability. Temporary labor is sometimes used to fill gaps, but the path to citizenship is neither automatic nor casual.

Singapore relies heavily on foreign workers in construction, domestic service, and other sectors. Yet it makes a sharp distinction between temporary labor and citizenship. Workers usually live in separate housing and return home when contracts end. Citizenship and permanent residence are reserved for those who meet explicit criteria, demonstrate economic contribution, and fit within the society’s long-term plans.

Western Europe provides examples of both overconfidence and correction. France, Germany, Sweden, and others expanded welfare states and admitted large migrant inflows in the belief that economic security alone would ensure integration. Instead, many urban areas developed parallel communities with lower employment, weaker attachment to the national identity, and higher levels of unrest. Governments responded with language requirements, integration courses, and tightened enforcement. Some also restricted access to benefits for recent arrivals.

Mexico’s own policies are stricter than many Americans realize. Unauthorized entry is a criminal offense. Foreigners cannot vote or involve themselves in domestic politics. Immigration agents conduct document checks. Cooperation with the United States has varied over time, but Mexico enforces boundaries in ways that would be considered controversial if the same measures were proposed in Washington.

“Melting pot” never meant endless protests, waving foreign flags, or burning the American flag. It meant different people choosing to become one country.

Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates rely heavily on foreign labor but do not offer citizenship paths. Residence is conditional upon employment and adherence to strict rules. When work ends, so does legal residence. This model is not suitable for a country like the United States, but it demonstrates that even societies built on imported labor understand the need for clear lines.

What these examples share is not a single template, but a common assumption. A country has the right and the responsibility to decide who may enter, under what conditions, and in what numbers. Most nations treat this as ordinary governance. The United States, by contrast, often treats border policy as a referendum on its collective virtue.

The Deep Cultural Loss Beneath the Bureaucracy

The most painful consequence of the immigration bureaucracy is not the money spent or the inefficiency it produces. It is the erosion of the quiet, everyday America that once held the country together without needing an army of translators, consultants, and administrators to do what neighbors once did themselves.

The expansion of NGO networks, federal agencies, and advocacy groups replaced something that cannot be recreated with budgets. It replaced the human connections that define a functioning society. Schools that once taught children the same history now juggle dozens of linguistic and cultural accommodations. Communities that once shared a basic civic understanding now operate through parallel institutions. Hospitals that once served a stable local population now operate as triage centers for national policy failure.

What disappeared was not wealth. It was simplicity. It was familiarity. It was the assumption that the person across from you in line, at school, or at church understood the same basic story about the country. It was the belief that Americans, regardless of background, shared a common world.

That cohesion has been replaced, piece by piece, by a bureaucratic management system. Entire offices exist to mediate cultural misunderstandings that would never have existed in 1965. Agencies produce translations for citizens who were never given the expectation to learn English. Local governments spend more on managing diversity than cultivating unity. The replacement of civic confidence with administrative complexity is not progress. It is a symptom of a society maintaining relationships through paperwork because it lost the ability to maintain them through culture.

This is the gut-wrenching truth:

As the bureaucracy grew, the America that once made immigration success possible slowly shrank.

The older model worked because newcomers entered a stable, confident culture that asked them to join it. The modern model assumes that the culture must adjust to every newcomer instead. No amount of funding can recreate what was lost when assimilation became optional and national identity became negotiable.

The bureaucratic system is not merely large. It is a monument to the vacuum left behind when the country stopped believing that becoming American meant joining something already established.

What Recent Years Reveal About Enforcement

The period from 2021 to 2025 illustrates how quickly border conditions respond to policy choices.

The Biden administration, beginning in 2021, adopted an approach to border management that emphasized humanitarian parole, release pending hearings, and narrowed interior enforcement. Asylum officers processed many claims at or near the border. Migrants who passed initial screening were often released with notices to appear in court at some future date. Detention was used more selectively. Sanctuary policies remained in force in many cities.

Border encounters rose to historically high levels, with more than two million recorded in multiple fiscal years. Many migrants turned themselves in to authorities because experience and word-of-mouth suggested that the likely outcome was release into the interior. Smuggling networks adjusted to the new reality, advertising the changed policies throughout the hemisphere. The system became overloaded. Processing centers filled. Cities far from the border struggled to house and support new arrivals.

The immigration court backlog grew above three million cases. Hearings were often scheduled years ahead. Asylum claims piled up faster than they could be adjudicated. Local governments requested federal funds to manage the influx. The capacity of schools, shelters, and hospitals was stretched. Compassion in theory translated into chaos in practice.

The change in administration in 2025 brought a change in approach. The Trump administration expanded fast-track removal procedures, increased worksite enforcement, negotiated renewed cooperation with Mexico on border control, and reinstated a version of the Remain in Mexico policy that kept many asylum seekers outside the United States while their claims were processed. Detention use increased. Interior enforcement broadened.

Within months, border encounters declined significantly from their 2024 levels. While still high compared to mid-twentieth-century norms, they reflected a clear pattern. When consequences for illegal entry were predictable and swift, fewer people attempted the journey. When consequences were uncertain or mild, attempts rose.

This pattern has appeared repeatedly in past decades. The lesson is not mysterious. People respond to incentives. They make decisions based on what they believe is likely to happen, not what officials say should happen. A system that promises enforcement but practices release will encourage more illegal entry. A system that actually enforces its own rules will reduce it.

Deterrence in this context is not an act of cruelty. It is a recognition of human behavior. A stable immigration system must create predictable expectations. Without that, border management will alternate between crisis and temporary reprieve.

What a Stable Framework Would Require

The United States does not lack laws. It lacks coherence. A stable immigration framework would not need to reinvent the country. It would need to match ideals with capacity.

Such a framework would enforce existing laws consistently. This would include meaningful border control, employer verification to reduce demand for unauthorized labor, and timely removal of those whose asylum claims fail. Strengthening enforcement does not mean eliminating legal pathways. It means making illegal pathways less attractive.

Admissions would be set in line with the society’s ability to absorb newcomers. That would require an honest assessment of school capacity, housing stock, and labor markets. It would require acknowledging that public tolerances matter. A policy that looks generous on paper but overwhelms local institutions is not generous in practice.

Selection criteria would place greater weight on skills, education, and language proficiency while reserving protection for genuine refugees. Extended family categories that multiply each initial immigrant into multiple future admissions could be narrowed. Those changes would not end family reunification, but they would limit its ability to drive large-scale demographic change.

Assimilation would return as a public expectation. English proficiency and basic civics would be required for long-term residence and citizenship, with straightforward paths for newcomers to acquire them. Adult education would be expanded where necessary, and the reliance on permanent translation systems would be reduced. The message would be that learning English and the country’s civic framework is part of the opportunity being offered.

Funding for nonprofit partners would be transparent. Organizations performing public functions with public money would disclose their advocacy activities. The public would be able to see where incentives lie and decide whether they align with the country’s long-term interests.

Local governments would be consulted before large numbers of newcomers were placed in their communities. Capacity in housing, employment, and public services would shape decisions, rather than being an afterthought.

None of these steps requires hostility toward immigrants. Many immigrants themselves favor clear rules and stable conditions. The people who follow the rules generally have the most to lose from systems that do not take rules seriously.

Remembering What a Nation Is For

Every society, whether it states it explicitly or not, builds itself around a few basic answers. Who are we. What do we share. What do we owe each other. What does it mean to join us. A country does not have to recite these answers every day, but it has to live by them. When the answers become confused, institutions become confused. Immigration policy becomes one more place where that confusion shows.

For most of American history, the answers were sufficiently clear. A person could come from many places, but once here the expectation was to become American in language, loyalty, and civic participation. That expectation was not always lived out perfectly. Discrimination and injustice were real. Yet the framework held because the society believed in itself strongly enough to ask newcomers to join its story.

The decades since 1965 have shown something that earlier generations did not fully anticipate. It is possible to grow faster than you can assimilate. It is possible to expand compassion faster than you can maintain coherence. Immigration policy did not become problematic simply because numbers rose. It became problematic because clarity fell. The country continued to hold out opportunity while reducing the expectations that made opportunity sustainable.

Many citizens now live with a sense of disorientation. They see schools struggling to serve ever more varied needs. They see hospitals absorbing costs that ultimately fall on taxpayers. They see wages stagnate while population rises. They see laws enforced in some places and ignored in others. They see debates framed in moral slogans rather than grounded in institutional capacity. Behind their frustration lies a simple question. When will policy return to common sense.

These concerns are not a mark of extremism. They are a sign that people still expect their government to balance generosity with responsibility. A nation can care about the hardships of people abroad while recognizing obligations to its own citizens. It can value immigration while seeing that unmanaged inflow strains the systems that residents and newcomers rely on. It can be open without being reckless.

Borders are not symbols of hatred. They are tools of stewardship. They allow a nation to determine how many people it can responsibly absorb and under what terms. They help citizens believe that laws are meaningful. They help immigrants understand what is being asked of them.

If the United States is to regain coherence, it will have to recover this understanding. The central question is not whether immigration is good or bad, but whether the system surrounding it is rational and sustainable. A rational system balances opportunity with capacity. It enforces laws predictably so that incentives point toward order. It articulates a civic identity that people can actually join.

Other nations have adjusted their policies as experience taught them hard lessons. The United States has the same opportunity. It can acknowledge that institutions have limits, that assimilation requires confidence in one’s own culture, and that compassion must operate within boundaries if it is to last.

Immigration is about who comes in. It is also about what they are being invited into. A society that remembers its own purpose can integrate newcomers successfully. A society that forgets its purpose will eventually fail both its citizens and its immigrants.

The country that once knew how to turn strangers into fellow citizens still exists in memory and in principle. The question is whether it intends to remember what that required.

Help Restore a Country That Still Belongs to Its Citizens

Become a Paid Subscriber

If this work matters to you, I hope you will consider becoming a paid subscriber. I write pieces like this full time. There is no institution, foundation, or political machine behind it. There is only the belief that telling the truth about what is happening to our country is still worth the cost. Your support makes this possible.

Make a One-Time Gift

If a subscription is not the right fit, a one-time contribution helps me keep the lights on and buy the hours it takes to produce research-heavy essays like this. Every bit of support strengthens independent work in a time when clarity is in short supply.

Join The Resistance Core

For those who want to take a larger role in sustaining this project, The Resistance Core is the top-tier level of support. These are the readers who make it possible to keep going when the work gets heavy and the subjects get uncomfortable. If you believe the country is worth fighting for, this is where that belief becomes action.

What Your Support Builds Right Now

You are helping build a platform that refuses to call confusion compassion. You are helping create research-driven pieces about immigration, governance, culture, media manipulation, and the slow erosion of national coherence. You are helping ensure that someone is still willing to say what many Americans feel but are pressured not to speak.

If You Cannot Give

You can still help. Share the essay. Post it in places where the conversation has gone silent. Send it to someone who needs to see that the facts still matter. The country needs more honest voices, not fewer.

Sign Up for the Boost Page — Free

You can also sign up for the Boost page at no cost. It helps push these essays into the larger conversation so they do not get lost in the noise.

“Hard times create strong men, strong men create good times, good times create weak men, and weak men create hard times”.

The Founders of this Country bequeathed us a system of government that led to generations of success. Unfortunately, as your essay illustrates so well, in that success lay the seeds of our eventual destruction.

“A republic, if you can keep it” was Benjamin Franklin's response to Elizabeth Willing Powel's question: "Well, Doctor, what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?"

The current generations of Americans are in the process of showing him they couldn't.

Another fine column. Assimilation is a major key.