Is Liberalism a Mental Disorder?

Spoiler Alert: It Is!

Every era produces a voice that says the things people sense but cannot quite express. For much of modern American talk radio, that voice belonged to Michael Savage.

I grew up in Millbrae, California, about fifteen or twenty minutes south of downtown San Francisco. The Bay Area offered a little of everything, quiet suburbs, a dash of grit, and the Pacific always near enough to remind you that the world outside was bigger and rougher than it looked from the hills. At twenty, I joined the Army, partly because I wanted to serve and partly because I knew if I got too comfortable, I might never do anything that hard again. I had a girlfriend, a decent job, played in a rock band, and probably could have gone on just fine. But I felt that staying comfortable too long makes a man soft, so I went.

When my military time ended, I stayed overseas and worked in a small German printing shop. The town had been peaceful for centuries; locals used to say it hadn’t seen a serious crime in two hundred years. Then, after the fall of the Czech and East Berlin walls, everything changed. People flooded across borders looking for opportunity or escape, and along with them came the troubles that open borders always carry. Within a year, that quiet town had its first daylight robbery at knifepoint, the first ever recorded there. My German friends asked why I was leaving, and I told them, “You don’t know what is coming. I can see it.” The crime, the coming Euro, the socialist regulations I saw on the horizon, all of it arrived soon after, and it hit them hard. That experience taught me how quickly order can unravel when nations forget the value of their own boundaries.

I came home in 1993, just before The Savage Nation reached the airwaves. I wasn’t following politics much then. Bill Clinton seemed fresh, young, articulate, and I thought maybe that was what America needed. Still, I had always known right from wrong, smart from stupid, and honesty from empty talk. At that point, I still believed everything I heard on 60 Minutes each Sunday night. It was the era when people trusted television because it sounded authoritative.

That way of thinking changed in 1998 when I read Booker T. Washington’s Up From Slavery. Washington’s voice was calm but unwavering. He stressed discipline, self‑reliance, and moral clarity, values that sounded old‑fashioned in the media but rang true to me. Reading him made me question what I had been told about race, merit, and history. It was the start of an awakening.

Back then, I listened mostly to sports radio. One evening, while dialing around, I caught a man on AM radio whose voice practically vibrated with energy, half scholar, half street fighter. At first the intensity put me off, but something made me keep listening. The man was Michael Savage. I soon found myself tuning in every night. The more I listened, the more I realized that what he was describing matched what I had already seen overseas: borders in collapse, bureaucracies growing while citizens shrank. Some of his rants sounded over the top, but the core of them felt right. He was describing the world as it was, not as television wished it to be.

Before Savage ever opened a microphone, he had been a scientist with advanced degrees in botany, medical anthropology, and a Ph.D. in nutritional ethnomedicine from the University of California at Berkeley. His early career was in academia and health research, not politics. He was the sort of person who measured conclusions against evidence. That habit never left him, even after he left the laboratory for the broadcast studio.

By the time his show The Savage Nation began in 1994 on a small San Francisco station, the country’s politics had grown stale and predictable. The Republican establishment talked about balanced budgets while the Democrat Party spoke about “compassion”, and both ignored the growing sense that something was breaking underneath. Factories were closing, neighborhoods were changing rapidly through illegal immigration, and ordinary people felt their country slipping away. Savage gave that anxiety words. He called his philosophy “Borders, Language, and Culture,” arguing that every successful society has boundaries. It knows who belongs, how its people communicate, and what they share. Remove any of those three and the whole cultural immune system collapses.

His message caught on fast because it spoke to reality, not slogans. By 2009 over twenty million listeners a week tuned in, making The Savage Nation the second‑most‑listened‑to radio program in America, trailing only Rush Limbaugh. He was not smoother than Limbaugh or more polished than Hannity, but he was unpredictable and willing to follow evidence wherever it led. His audience was large enough that advertisers and political consultants could not ignore him, yet his independence made them nervous. When he said in 2005 that “the conservative movement is dead,” he was not exaggerating. Voters might have leaned conservative, but Washington’s self‑declared conservatives had become what Savage called “managers of decline.”

The context of that moment helps explain why his book Liberalism Is a Mental Disorder resonated. The war in Iraq had dragged on, the national debt had doubled since 2001, and both parties had backed trade and immigration policies that kept wages flat for two decades. Economists at the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that by 2005 the average factory worker earned about sixteen dollars an hour in inflation‑adjusted terms, the same as in 1978.

Meanwhile, elites in banking, entertainment, and politics lectured the public about global citizenship while insulating themselves from its consequences. Savage was scornful of that class, calling them “borderless men with borderless loyalties.”

His critics dismissed him as angry, but anger, in his view, was the right response to a country losing its bearings. He drew on history and anthropology to show that civilizations die not because of foreign invasion alone, but because they lose the cohesion that made invasion costly. That was the logic behind Borders, Language, and Culture. Borders define the space a nation protects. Language binds people to shared meaning. Culture unites them through moral codes and traditions. Remove those and strength turns to sentimentality.

When Savage warned that “America’s elite has a mental disorder that masquerades as virtue,” he was speaking about a broader sickness: what happens when compassion becomes a substitute for competence and guilt replaces gratitude. His program sounded more like therapy sessions than old‑style political talk. He discussed vitamin deficiencies, immigration law, literature, and sometimes his dog. Yet behind those digressions was a consistent message: a society unwilling to defend itself, whether biologically or morally, will decline in health just like a patient who refuses treatment.

In the years since he made that diagnosis, events have justified his warnings. The failures in global finance, the distrust in centralized medicine after the pandemic, and the return of nationalism throughout the Western world all echo questions Savage raised long before they were fashionable. He saw the border not merely as a geographic line but as a symbol of order itself, the point where self‑definition begins. And a prophet of the border is exactly what he became.

Savage’s work prepared the ground for a rethinking of what conservatism even meant. To him, party labels had lost meaning because both sides spoke in abstractions while ignoring everyday reality. He argued that any real movement of renewal would have to begin with telling the truth about what had gone wrong. That is the purpose of his 2005 preface, which read less like an introduction and more like an autopsy. It dissected not liberalism, but a conservative establishment that had forgotten its spine.

The Funeral of Conservatism

When Michael Savage opened his 2005 book Liberalism Is a Mental Disorder with the words “The conservative movement is dead,” it was not a declaration of defeat but an autopsy report. He believed that the principles of conservatism, self‑reliance, national pride, and moral discipline, had been quietly abandoned by those claiming to defend them. What remained in Washington were political technicians who managed the steady decline of the country while pretending to resist it. His frustration was not with America’s people but with leaders too timid to stand for the borders, language, and culture that define a nation.

By the early 2000s, many Republican lawmakers had grown comfortable with the same global system that the Democrat Party’s progressives celebrated. Outsourcing was enriching corporate donors. Immigration was supplying cheap labor. Federal spending was ballooning just as fast under Republicans as it had under Democrats. In 2005 the Congressional Budget Office reported that federal outlays had increased by nearly one‑third since 2000, even before the costs of new wars and entitlement expansions were counted. To Savage, that was proof that conservatism had ceased to conserve anything.

He used the Arizona Proposition 200 fight as his example. Voters there had approved a measure requiring proof of citizenship to vote and barring illegal immigrants from collecting state benefits. Washington elites from both parties called it cruel. Even foreign governments scolded Americans for wanting to enforce their own laws. Savage pointed out that when the Mexican government threatened international legal action against Arizona, the State Department did not even defend an American state’s right to police its own elections. The message from Washington was simple: sovereignty had become an embarrassment. Savage saw that as a form of collective dissociation, the national equivalent of a person who loses awareness of his own boundaries.

He called the ideology behind this erosion “soft communism,” a system of bureaucratic control disguised as compassion. Instead of national loyalty, people were asked to show loyalty to a global vision that transferred power to unelected administrators in international institutions. He cited proposals by European leaders such as Jacques Chirac to impose global taxes for humanitarian causes as evidence that Western elites were converging toward a managed world economy rather than accountable self‑government. By 2005 the European Union had already begun issuing regulations with direct economic consequences for American companies, from data privacy to agricultural standards. Savage warned that these efforts were not acts of coordination but attempts at control, the steady replacement of self‑rule with moral grandstanding.

The weakest link in this political chain, he argued, was spiritual rather than economic. When a civilization loses its moral compass, it soon loses the will to defend itself. Across Europe, and increasingly in the United States, secular elites mocked traditional religion while embracing vague moral relativism. The result was a decline not of faith alone but of standards. Savage compared this to the collapse of immune defenses in a body: when morality weakens, infection spreads, whether in a culture or an organism.

Yet even in his criticism, his writing contained a peculiar optimism. He still believed that America’s instincts were healthy and that the problem lay in a political class unwilling to channel them. He argued that humor could become a form of resistance. “Expose our enemies by mocking our enemies,” he wrote, reminding readers that ridicule deflates propaganda more effectively than anger. That approach made Liberalism Is a Mental Disorder far livelier than most political books of its time. It was half diagnosis, half stand‑up routine, a kind of intellectual shock therapy meant to awaken a sleepwalking nation.

By the end of the preface, Savage issued a call for what he called “a new American nationalism.” It would not be defined by race or party but by an unapologetic defense of civilization itself. He wanted leaders who could say out loud that borders are not racist, that language is not oppressive, and that culture matters more than slogans. It was a radical thought for 2005, years before populist movements in either party would rediscover those themes. In hindsight, his preface reads less like a relic of a past debate and more like an outline of the political upheaval that would soon come.

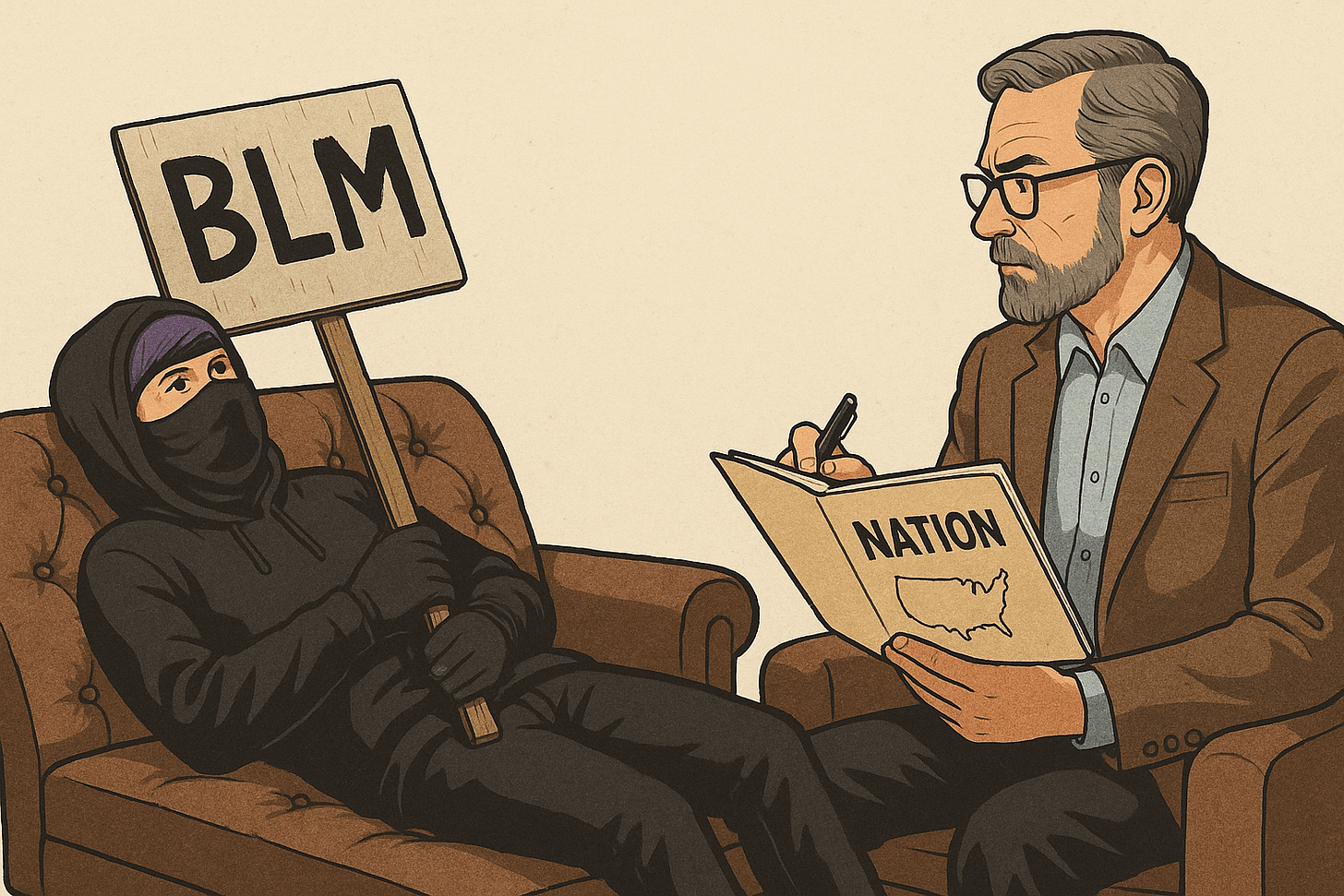

The Savage Framework: Liberalism as Pathology

To Michael Savage, political problems are rarely only political. They are psychological. A nation’s laws, ideals, and even its quarrels grow out of certain emotional habits. In Liberalism Is a Mental Disorder, he treated liberal ideology not as a competing philosophy but as a pattern of dysfunction, symptoms that can be observed, described, and often predicted. He drew from his background in anthropology and nutrition science to illustrate that the mental habits of a culture function much like the biological systems of the body. When they work together, a society remains stable. When they are distorted by self‑deception or excess, decline follows.

His first diagnosis was what he called narcissistic altruism: the need to be seen as virtuous rather than to actually do good. He noticed how political leaders and celebrities adopted causes chiefly for applause. Government programs claimed to help the poor while discouraging work, or to help minorities while lowering expectations. During the 1990s the number of Americans receiving some form of federal assistance roughly doubled, yet the poverty rate barely moved. Savage argued that compassion had been redefined as the act of spending other people’s money while congratulating oneself for generosity.

The second disorder he described was moral masochism: a form of self‑blame so intense that it turns guilt into identity. Instead of patriotism or gratitude, citizens are taught to dwell on collective sins. By the early 2000s, university surveys found that a majority of students viewed American history primarily as a record of oppression. Savage warned that when guilt becomes a national posture, it paralyzes a people. They stop defending themselves because they no longer believe they are worth saving.

A third symptom was cognitive dissonance denial. Governments, like individuals, sometimes ignore facts that contradict their beliefs. City officials in San Francisco, for example, promoted “sanctuary” policies claiming they made the city safer. Yet Justice Department data later showed violent‑crime rates among illegal immigrants to be higher than among legal residents, especially for serious repeat offenses. Savage argued that evidence no longer mattered when ideology replaced observation.

Then came projection and authoritarian inversion. Those who call themselves tolerant increasingly used government or social pressure to silence anyone who disagreed. He noted how groups claiming to fight “hate” destroyed professional reputations and livelihoods over political differences. The mechanism looked psychological rather than political: the accuser projecting inner hostility onto others while posing as defender of virtue.

Beyond those, Savage spoke of dependency disorder, the worship of the parent‑state. As federal programs multiplied, personal responsibility faded. By 2005 roughly half of American households received some direct payment from the federal government. Savage believed that when people depend more on bureaucracies than on their own efforts or families, individual initiative becomes a threat to those in power.

He also described compassion addiction, the constant need for moral drama. Social media would later amplify it, turning outrage into entertainment, but Savage saw the pattern early. Without struggle, many find no meaning; without victims, they find no purpose. The result is permanent agitation that solves nothing. Finally he pointed to utopian delusion, the idea that human perfectibility can be engineered through policy. Differences in talent, culture, and effort are denied, and inequality becomes not a human constant but a crime to be punished. The pursuit of this impossible equality, he warned, would justify endless control.

Taken together, these habits form what he called a national neurosis: a culture so inflamed by self‑pity and denial that it cannot perform the basic duties of civilization. His framework may sound severe, but it matched observable trends. By 2020 the United States was spending over one trillion dollars a year on income‑transfer programs while educational achievement continued to fall and rates of depression and substance abuse climbed. The disorders he identified were not metaphors anymore; they were visible in charts and hospital admissions.

Savage concluded that unless the country addressed the psychological roots of these problems, politics alone would change nothing. Laws enacted by disoriented minds would only reproduce disorientation. Liberals might sneer at the diagnosis, but the symptoms were growing harder to ignore. A society addicted to its own abstractions cannot remain sane indefinitely.

Supplemental Diagnoses:

Disorders Beyond Savage

Although Michael Savage described the emotional core of modern liberalism nearly twenty years ago, the landscape of 2025 reveals that the condition has metastasized beyond even his early prognosis. He would likely recognize the same impulses; envy, guilt, utopian longing, but expressed through new technologies and cultural rituals. To understand the modern form of what he diagnosed, it helps to look at a few disorders that have developed since his book appeared.

The first is reality dysmorphia, the collective ability to deny physical or biological facts in favor of feelings. Biology used to be among the least controversial fields. By the early 2020s, it had become a political battlefield. In classrooms and clinics, factual statements about sex differences could end careers. Teachers in several states were disciplined for using biological terms that only a decade earlier were considered standard. A 2023 Gallup poll found that nearly 30 percent of Americans under thirty believed that “human sex is a social construct.” This is not disagreement about policy; it is confusion about reality itself. Savage would see this as the final stage of cognitive dissonance denial, when ideology triumphs so completely that evidence no longer registers.

Closely related is narrative dependency syndrome, the tendency of entire populations to live inside stories crafted by media and reinforced through constant repetition. Facts now serve the story rather than shape it. During the pandemic, the same statistical data were interpreted in radically different ways depending on a network’s political leaning. In the 2024 campaign, economic indicators were spun as proof of success or failure depending on who reported them. It created an environment where perception mattered more than numbers, and loyalty replaced reasoning. The average American spent seven hours a day interacting with digital media by 2022, according to Nielsen research, giving this syndrome a vast supply of reinforcement every waking hour.

Collective identity dissociation has grown alongside it. This is the psychological fragmentation of common culture into warring tribes of grievance. Where previous generations fought for civil rights under a shared moral language, modern activism separates populations into categories competing for moral victimhood. Universities, businesses, and government agencies have normalized the idea that identity determines truth. The result is mistrust and fatigue. A 2025 Pew survey found that only 16 percent of Americans believed their fellow citizens “trust one another.” Savage’s earlier claim that “liberalism breeds chaos through kindness” now describes daily life in many institutions.

The fourth disorder is techno‑induced empathy erosion. When people live through screens, empathy becomes a form of performance rather than understanding. Social networks reward outrage and moral posturing more than patience or compassion. Neuroscience studies at Stanford showed that frequent social‑media users display lower activity in the anterior cingulate cortex when confronted with others’ pain, a physiological marker of declining real empathy. Savage was among the first to warn that technology, if combined with ideology, would make people emotionally numb while convinced they are virtuous.

Finally there is pseudo‑therapeutic authoritarianism. This is the growing belief that safety is the ultimate moral good and that the role of government is to shield citizens from all discomfort. Officials now justify censorship, financial surveillance, and even restrictions on movement in the name of “public health” or “well‑being.” During 2020–2022, safety became the universal rationale; by 2025, that logic had migrated to nearly every policy issue. It is why bureaucracies talk in the language of mental health while they centralize power. The citizen becomes a patient, and the government becomes the therapist who never surrenders authority.

These five disorders, layered on top of Savage’s original seven, complete the present condition of the Western mind. They describe a civilization overwhelmed not by deliberate tyranny, but by emotional reasoning, endless distraction, and the fear of personal responsibility. The dangers he warned about are no longer theoretical. Every major indicator of psychological health, depression rates, youth anxiety, substance addiction, shows steady increase despite record public spending on therapy and social programs. The numbers suggest that external treatment cannot cure an internal confusion about meaning.

Understanding these new expressions of the original illness sets the stage for the next question: what happens when this psychological disarray becomes institutionalized, when whole governments begin to operate under the logic of learned helplessness? That is where the story of the past twenty years leads.

From 2005 to 2025: The Full Bloom of the Disorder

By 2005, Michael Savage was describing liberalism as a psychological ailment, but few imagined that two decades later those emotional impulses would become the dominant structure of Western institutions. What began as ideological eccentricity in universities and newsrooms gradually captured corporations, government agencies, and international organizations. The symptoms he identified, dependency, guilt, utopian delusion, became the blueprint for how those institutions operate. The years between 2005 and 2025 mark the period when that framework grew from dysfunction into a governing philosophy.

The rise of what might be called the bureaucratic psyche explains much of it. The modern bureaucracy believes it can engineer morality through regulation. Programs that once measured success by outcomes now measure it by intentions. Environmental policy provides one example. In 2005 the Environmental Protection Agency managed roughly 9 billion dollars in climate‑related grants. By 2025 that figure is projected to exceed 50 billion, yet global carbon emissions have continued to rise according to the International Energy Agency. The more the policy fails, the more expansive the bureaucracy becomes, because failure justifies greater control. Savage’s warning about “soft communism” captured this psychology exactly: an administrative class seeking salvation through management.

Academia solidified as the Vatican of this new orthodoxy. Departments that once explored ideas became gatekeepers determining which ideas could be spoken. Studies from the Higher Education Research Institute show that by 2021 roughly 80 percent of social‑science faculty identified as liberal while less than 10 percent identified as conservative, a ratio far sharper than in 2005. The result has been not progress but stagnation. Entire fields now recycle moral slogans as research. Savage foresaw this, arguing that when institutions prize conformity over inquiry, knowledge decays under the weight of certainty.

Information itself turned into a sedative. With the expansion of digital media, citizens are bombarded with curated narratives designed to steer emotion rather than reason. During the pandemic, for instance, anyone questioning federal health policy risked being banned from major online platforms. Freedom of debate, which once drew strength from competition of ideas, has been blended into what Savage might call a “therapeutic censorship.” The objective is not persuasion but avoidance of discomfort. This infantilization of public discourse has produced record cynicism. According to a 2025 Gallup survey, only 7 percent of Americans report high confidence in mainstream news outlets, the lowest level recorded.

The social consequences have been visible everywhere. By the mid‑2010s loneliness had reached measurable epidemic levels. The U.S. Surgeon General’s 2023 report noted that lacking social connection carries health risks equivalent to smoking fifteen cigarettes a day. Child and adolescent mental‑health visits doubled between 2010 and 2020 even as federal spending on behavioral programs nearly quadrupled. The culture that promised liberation through self‑expression has produced a generation unsure of its own purpose. Savage argued that when culture rewards perpetual childhood, many will choose not to grow up. The average age at which Americans marry or have a first child is now the highest in recorded history.

Technology amplified every disorder Savage described. Smartphones became intravenous lines to the collective nervous system, flooding people with stimulation while draining focus. Social‑media engagement depends on outrage; despair becomes monetized attention. Researchers at the University of Michigan found that adolescents who spend five hours or more a day on social media are twice as likely to report severe anxiety. Instead of uniting a nation, personal screens have isolated it into millions of private stages for self‑advertisement.

Even the ideal of global unity proved illusory. The European Union’s expansions and economic controls were sold as a model of enlightened cooperation, but by 2016 economic stagnation and rising immigration pressures drove British voters to leave. Savage had called the EU “Hitler’s dream of a united Europe under German control,” an intentionally harsh warning about the dangers of centralized authority. The outcome of Brexit, and later similar movements in Italy, Poland, and the Netherlands, confirmed that people do not remain loyal to abstractions. They are loyal to home, language, and shared memory.

The COVID‑19 years showed how those tendencies interact under stress. Governments imposed uniform lockdowns as if human beings were spreadsheets rather than communities. Savage, who holds training in epidemiology, early on described the virus seriously but resisted the wholesale surrender of liberty in the name of safety. He warned that “a nation that treats its citizens as children will raise citizens who behave like children.” The permanent expansion of health mandates, the censorship of dissent, and the ongoing distrust in public medicine two years after the pandemic all validate that point. Safety became a creed, and fear its sacrament.

In short, the period from 2005 to 2025 represents the full bloom of the national neurosis Savage diagnosed. Materially, the United States remains wealthy and powerful, but emotionally it shows the symptoms of exhaustion. The persistence of debt, division, and despair suggests that the liberal project to perfect mankind through management has reached its peak. What comes after will depend on whether the country rediscovers the virtues Savage considered foundational, the ones now personified by a political movement he could not have foreseen but often described in spirit.

The Savage Prophecy and the Trumpian Fulfillment

When Donald Trump entered the 2016 race, analysts tried to fit him into familiar categories. To some he was a populist, to others a nationalist, or a reality‑television opportunist. What few noticed at the time was that he was channeling themes Michael Savage had been articulating for decades. The issues that dominated Trump’s rallies, borders, national pride, trade, and defiance of political correctness, were echoes of Savage’s three‑part formula, Borders, Language, and Culture. Listeners who had grown up with The Savage Nation recognized the cadence instantly.

Between 1994 and Trump’s first campaign event in 2015, Washington’s political class had lost almost all moral credibility. Republican and Democrat elites had overseen twenty years of outsourcing, open borders, and foreign wars that achieved little except debt. Savage’s phrase “managers of decline” described them perfectly. He had already announced the death of conservatism ten years before Trump entered politics, arguing that the movement’s leadership class had become a timid bureaucracy incapable of passion or purpose. Trump became the living rebuttal. He transformed bluntness into a political weapon, using ridicule in exactly the way Savage suggested years earlier: to unmask hypocrisy through laughter rather than apology.

Trump’s success in 2016 surprised the same power brokers who had dismissed Savage as fringe. But the reasons were plain to anyone outside the Washington echo chamber. Median incomes had stagnated for more than a decade while urban housing costs doubled. The Census Bureau reported that by 2015, household incomes in the lower half of the distribution had fallen by roughly 4 percent since the year 2000, even as corporate profits reached record levels. Trump’s vow to renegotiate trade deals, build a border wall, and put Americans first was not extremism to his voters but common sense. He spoke to the practical frustrations Savage had been voicing since Bill Clinton’s first term.

Their connection was also personal. Trump often appeared on The Savage Nation and described himself as a listener. They shared an outsider’s contempt for credentialed mediocrity and a belief that patriotism was not a sin. Savage endorsed him early, calling the campaign “the last chance for national survival.” In later years, when they disagreed, on Syria, on John Bolton’s appointment, or on environmental protection, they did so from the standpoint of allies. Trump trusted Savage enough to appoint him in 2020 to the Presidio Trust’s board, a symbolic gesture that acknowledged his decades of cultural influence.

Trump’s arrival completed what Savage’s 2005 preface had predicted: the collapse of polite conservative moderation and the return of unapologetic nationalism. The political class that once mocked Savage now mimicked his vocabulary. Suddenly even establishment Republicans spoke of “sovereignty” and “American workers.” Democrat strategists denounced nationalism as dangerous, confirming that it had become potent again. The struggle Savage portrayed as psychological, between the instincts of self‑preservation and the illusions of global benevolence was now being fought in elections rather than seminar rooms.

When Trump lost power after the 2020 election, many expected the populist tide to fade. Instead, it deepened. By 2025 he had returned to office, winning every swing state and taking the popular vote, the first Republican in thirty‑five years to do so. His comeback proved that the forces Savage had identified were not a passing spasm of anger but a structural realignment. Working‑class voters in former Democrat strongholds such as Pennsylvania and Michigan continued shifting toward nationalism because it offered practical hope instead of slogans. Polling from the 2024 cycle showed that more than 60 percent of Americans agreed with the simple premise that “a country without borders is not a country.” That is the Savage thesis in statistical form.

Trump’s second term, beginning in January 2025, has been defined by policies that trace directly to that worldview. He tightened restrictions on illegal entry, restructured international aid around reciprocity, and emphasized cultural literacy in federal education funding. At the same time, he reduced military entanglements overseas, insisting that defending American interests began with defending its own towns. Whether one likes or dislikes Trump, these are precisely the priorities Savage had been urging long before he entered politics.

The connection between them is best understood not as imitation but as alignment. Savage was the philosopher of border realism; Trump became its practitioner. Where Savage held a microphone, Trump held an executive pen. Both spoke plainly to people tired of abstraction. In temperament they differed, Savage was sardonic, Trump theatrical, but the underlying conviction was shared: that national survival depends on clarity, confidence, and cultural pride.

Savage once wrote that anger is often a sign of health, that apathy is the symptom to fear. Trump’s political energy, for all its controversy, forced a moribund country to feel again. That may be his largest debt to the broadcaster who came before him. Together they restored emotion to a political vocabulary that had become sterile.

By the time Trump returned to the White House in November 2025, the link between their ideas was plain even to former critics. Each revolution begins with words before it takes shape as policy. The border prophet had spoken those words for years. The builder turned them into walls and treaties. Whether history judges them kindly or harshly, both men proved that realism and courage, once dismissed as anger, can move a sleeping nation to act.

Clinical Correlates:

Mapping Ideologies to Mental Disorders

When Savage compared political ideology to mental illness, he was not being cruel; he was being descriptive. He had spent too many years in research to think that societies behave rationally by default. Like individuals, they form habits of thought that can become maladaptive. Looking across the last twenty years, the parallels between certain dominant liberal ideas and recognizable psychiatric patterns have become difficult to ignore.

Radical equality illustrates the point. The idea that all differences in outcome result from discrimination has hardened into dogma. Under this view, unequal results must mean injustice, regardless of effort, skill, or circumstance. The belief resembles what psychologists classify as a grandiose delusion: a conviction that a perfect state can exist if only enough control is imposed on others. The real‑world effect has been perverse. In the name of fairness, many cities lowered educational standards, eliminating entrance exams for advanced programs to achieve “equity.” New York City’s school district did so in 2021, and math proficiency in the affected middle schools dropped by more than ten percentage points within two years. Where merit is treated as oppression, achievement predictably declines.

A second example is identity fixation, the insistence that personal identity determines truth. In mental‑health literature that kind of rigid self‑definition often appears in dissociative disorders, where the sense of self is both fractured and inflated. In politics, it becomes a sort of national multiple‑personality syndrome. Individuals retreat into racial, sexual, or political sub‑groups, each convinced it embodies virtue. The country loses the ability to think in shared terms. A Gallup survey from late 2024 found that 68 percent of Americans now describe the nation as “divided beyond repair.” That sentiment is not the result of debate but of excessive personalization of belief the same mechanism by which fragile egos mistake disagreement for violence.

Speech policing is another hallmark. The drive to control language for moral ends mirrors obsessive‑compulsive traits: an exaggerated fear that wrong words will bring catastrophe. Universities and corporations now devote entire departments to monitoring terms previously considered normal. 2023 data from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression listed more than 700 active speech‑restriction policies on American campuses, triple the number from 2005. The founding generation considered free speech a protective mechanism for truth; modern institutions treat it as a threat requiring supervision. The intent sounds noble, preventing harm, but the outcome is intellectual paralysis.

Then there is consensus worship, the assumption that truth can be determined by counting noses. Individuals who defer all judgment to authority figures exhibit dependency behavior, and whole populations can do the same. During the pandemic, citizens were told “trust the science,” as though science were a priesthood rather than a method of testing evidence. When later studies contradicted official claims about transmission or immunity, many people preferred silence over curiosity. That avoidance of responsibility, the confusion of agreement with accuracy, is the political form of dependency disorder. Systems that treat adults like children eventually create children in adult bodies.

These analogies may sound severe, but they mirror measurable trends. The United States has experienced simultaneous growth in both government oversight and private anxiety. In 2000, federal regulatory spending stood near 26 billion dollars. By 2025 it exceeds 80 billion. During the same period, clinical anxiety diagnoses more than doubled, reaching thirty percent among young adults according to National Institute of Mental Health data. The more life is managed by distant experts, the less confident individuals become in managing themselves. Savage’s framework helps explain why. External control cannot compensate for internal confusion.

The purpose of this comparison is not ridicule but clarity. When large social movements begin to mimic clinical symptoms, denial, obsession, dependency, it warns that emotion has overtaken reason. The solution is not punishment but maturity, just as the treatment for neurosis is reality testing. A nation that can look at its errors without hysteria can still recover. The next task, therefore, is to ask how such a recovery might occur, and what steps could restore the personal responsibility and clear thinking that once sustained American life.

Recovery Protocol: National Therapy

If Savage was correct that the country’s difficulties stem from psychological disorientation rather than purely political failure, then the remedy must begin with restoring mental balance. A sick body does not recover through speeches, and a disoriented nation cannot be repaired through slogans. What he called for, though he did not name it as such, was a form of national therapy, a process of regaining perspective through truth and responsibility.

The first step is detachment from propaganda. Every citizen now carries a personal propaganda device in his pocket. Algorithms feed each side a steady diet of outrage until people mistake emotion for knowledge. The only practical cure is deliberate withdrawal. A 2023 study from the University of Pennsylvania found that participants who limited social‑media use to thirty minutes a day reduced measured anxiety and depression within two weeks. The same discipline could heal public discourse. When people control their attention instead of renting it to corporations, they begin to think again.

The second step is exposure to reality. Ideology thrives on insulation. Communities that never encounter opposing ideas lose the ability to reason; they memorize talking points instead. One of the simplest acts of civic recovery is to restore curiosity. Individuals should read what opponents write, visit places where their assumptions are tested, and learn skills that yield tangible results. Savage often said that physical work clears mental fog. Data supports the point: outdoor labor and even household exercise strongly correlate with lower rates of anxiety and higher self‑esteem. A society filled with people who can fix real problems is less tempted to invent imaginary ones.

Third comes responsibility restoration. When government becomes the default caretaker, personal duty withers. Reversing that trend means pruning bureaucracy and returning competence to local levels. Over the last twenty years federal employment has grown by nearly twenty percent even as trust in government declined to historic lows. Voters who demand self‑government must accept that it requires self‑reliance. Stable countries, like healthy adults, are built on the habit of doing unpleasant things because they are necessary. Families that teach that principle produce citizens who need less supervision and more freedom.

A fourth stage is moral and familial reconstruction. Data from the U.S. Census show that children raised in stable two‑parent homes are roughly half as likely to drop out of school or fall into poverty. These are not moral preferences; they are practical realities. Savage linked family breakdown directly to national weakness because it erodes both discipline and empathy. Rebuilding family culture does not require new bureaucracies. It requires moral confidence, the courage to say some choices are better than others. Churches, synagogues, and civic groups still possess that authority if they are willing to use it.

Finally there must be a constitutional revival. Every strength the country once had is rooted in a document that defines limits. The Constitution’s checks and balances were written precisely to guard against emotional politics. Over the last two decades, both parties have expanded executive power while using emergency rhetoric to justify it. The correction is simple if difficult: re‑impose limits, demand transparency, and revive civic education so people know why those limits exist. When the citizen again becomes master rather than patient, the national mind will begin to heal.

Recovery on this scale cannot happen through policy alone. It must happen in households, local communities, and individual consciences. Treatment begins the moment people stop blaming unseen forces for every misfortune and start taking agency for their own conduct. A society that respects truth, accepts consequence, and rewards effort will naturally regain its equilibrium. That is the therapy Savage pointed toward: not a revolution of anger, but a recovery of sanity.

The Savage Truth Transcendent

Every civic argument eventually comes down to questions of meaning. When Michael Savage first said that liberalism had become a mental disorder, he was not insulting his opponents; he was asking what happens when societies confuse emotion with morality. Two decades later, the answer has become clearer. Political institutions now operate in the language of therapy. Activists admit their goals are emotional well‑being, not law or order. Yet despite vast programs and perpetual moral campaigns, anxiety, loneliness, and anger have all increased. That contradiction tells us something fundamental about human nature that Savage understood early: comfort cannot replace conviction.

In the final years of his career, Savage turned more spiritual. His book God, Faith, and Reason explored how belief gives structure to civilization just as biology gives structure to the body. He was never a churchgoer or a preacher, but he saw religion as an anchor of sanity. When faith erodes, people seek substitutes in politics, ideology, or entertainment. None satisfy for long. Survey data from Pew Research in 2024 showed that only about 63 percent of Americans still identify with any organized faith, down from near 80 percent at the turn of the century, while rates of depression and suicide have climbed steadily. The relationship is not coincidence. Cultures that lose a shared moral language start speaking in fragments.

Savage’s message endured because it connected conscience with evidence. He often reminded listeners that the words “conservation” and “conservative” share the same root. He argued that to conserve does not mean to exploit; it means to protect and to cherish. He became known as a champion of wildlife preservation, opposing trophy hunting and urging respect for creation. His interest in ecology was not an affectation but the natural extension of his politics. Just as individual discipline maintains personal health, human restraint maintains environmental balance. A culture that cannot conserve its forests will not conserve its freedoms either.

When Donald Trump invited Savage to the White House years later, partly to discuss those conservation issues, the symbolism was striking: the radio prophet who had defended national borders now advising the president on protecting natural borders of another kind, the line between stewardship and excess. That meeting summed up a career spent translating moral instinct into policy. Savage had begun by studying plants, by learning how ecosystems function. He ended by warning a nation that if it severed its moral roots, the entire civilization might wither in much the same way.

By the mid‑2020s, his influence remained visible even as his voice grew quieter. The populist realignment that brought Trump back to the presidency was built on the vocabulary Savage introduced to public life; sovereignty, gratitude, and truth spoken without apology. Whether one agrees with him or not, his arguments forced a generation to reconsider what sanity looks like in political form. Perhaps the clearest measure of his impact is that words once considered shocking; patriotism, merit, responsibility, have returned to ordinary conversation.

Savage ended most broadcasts with the phrase “God bless America,” but his deeper message was one of responsibility rather than sentiment. Blessings, he reminded listeners, come to those who protect what they have been given. His career showed how ideas, when spoken plainly, can outlive reputations and controversies. Trump revived nationalist politics; Savage restored its moral vocabulary.

If nations, like people, must tell the truth about their condition before they can heal, then the first step toward sanity is honesty. The liberal disease he diagnosed was self‑deception: pretending to be compassionate while destroying the structures that make compassion possible. The cure, he argued, was courage.

Healing begins when the patient stops pretending he is not sick.

Help Keep This Work Savage!

I do not have a university, a network, or a donor class behind me. It is just me at a desk trying to do the kind of work that dies when one person falls and no one else is there to carry it. If you want voices like this to keep going, they have to be able to survive rent, groceries, and real life, not just outrage and applause.

If you are able, you can help in three ways: become a paid subscriber so I can keep writing instead of scrambling for other work, make a one-time gift to keep the basics covered, or join The Resistance Core so I can plan bigger projects that last.

Free Boost Page (for creators who want to help widen the reach)

I am a fellow activist like Chris and send out a daily newsletter to my circle. Chris's essays are a perfect 10 by any measurement criteria. The truth that really matters, presented better than any highly paid journalist/reporter. PLEASE support him! He needs it to survive. Imagine the cost of NOT having him!

Fascinating article!