One Nation Under Fraud: How the 2016 Election Standards Were Dismantled

The Electoral College impact, the legitimacy crisis, and what comes next

This essay concludes a two-part analysis of the 2020 election under 2016 election standards.

Having established the rule changes and their state-level effects in Part One, this piece turns to the national outcome and what those changes ultimately decided.

“When small procedural changes determine national outcomes, the question is no longer who won — but whether consent still exists.”

Electoral College Recalculation and Implications

If you strip away the noise of the 2020 campaign and look strictly at the arithmetic, it becomes a lesson in how large consequences hinge on small numbers. When Americans hear that Joe Biden won by seven million votes nationwide, that figure can sound overwhelming, almost insurmountable. But presidential elections are decided by states, not by the national total. The Electoral College exists specifically to prevent large urban centers from swallowing the rest of the country, and in 2020 it performed its function almost too well — it revealed just how fragile the balance had become.

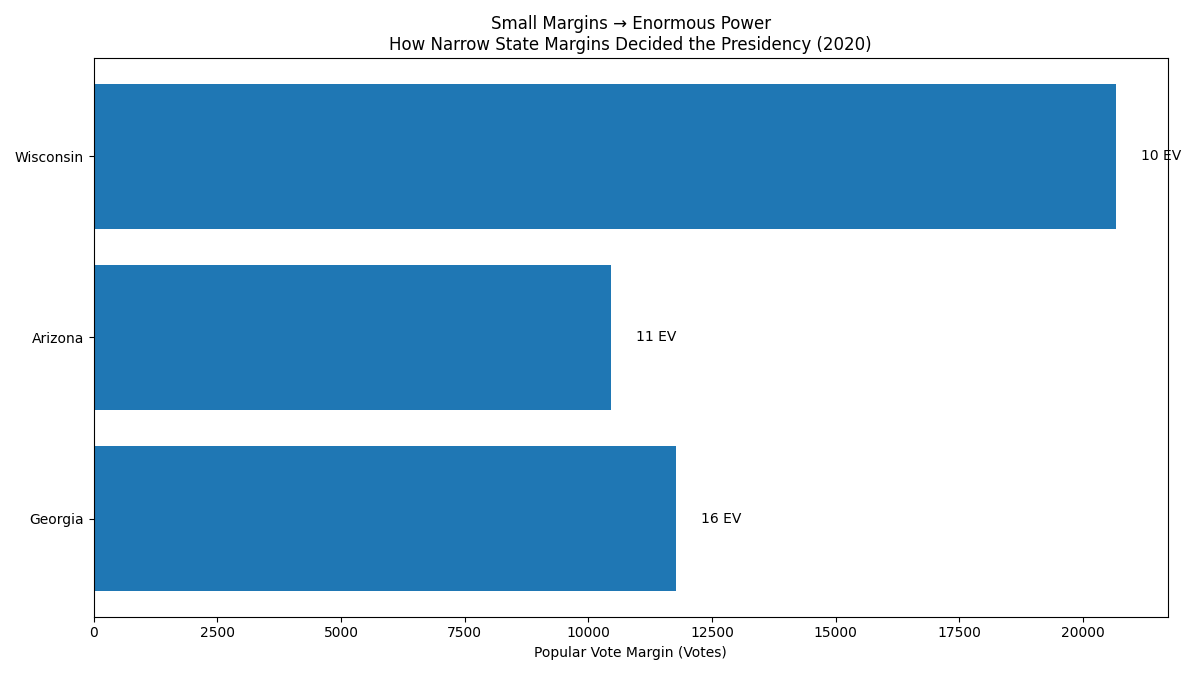

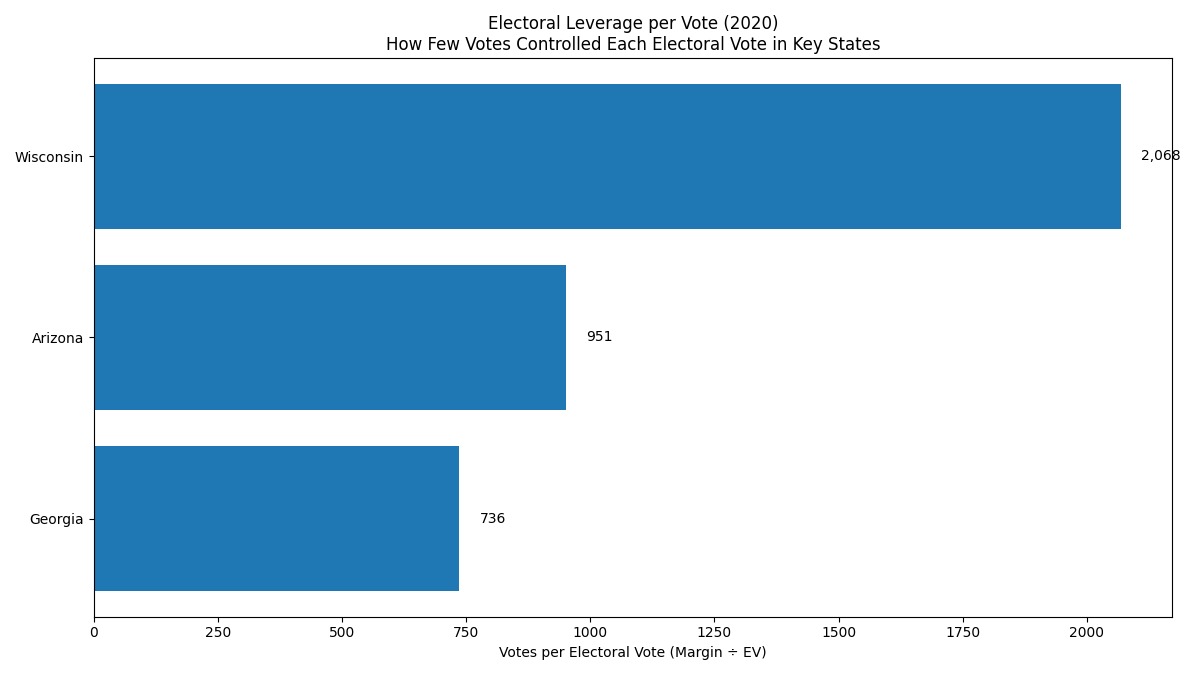

Using the corrected map under 2016 rules, the pattern of change is unmistakable. Arizona, Georgia, and Wisconsin swing from blue to red, bringing Trump to 269 electoral votes and Biden to 269. That tie, as the Constitution lays out in Article II and the Twelfth Amendment, would send the election to the House of Representatives. There, each state delegation casts one vote regardless of population size. As of January 2021, twenty‑six delegations were controlled by the Republican Party, twenty by the Democrat Party, and four were evenly split. A tie in the House under those numbers would have meant a vote for Trump.

Even a single additional state swinging red — Pennsylvania under the adjusted variables, for example — pushes Trump to 279 electoral votes against Biden’s 259. That outcome doesn’t just suggest a different winner; it demonstrates how the election hinged entirely on procedural flexibility. As much as pundits talk about “coalitions” and “demographics,” the practical coalition that won 2020 consisted of altered deadlines, emergency decrees, and tailored information control. Those substitutes for persuasion were enough to reshape the nation’s leadership.

The Fragility of the Modern Margin

To understand what that means, consider this: the United States has about 160 million voters. In 2020, the difference between the certified winner and a re‑elected president amounted to less than forty‑five thousand ballots across three states. In percentage terms, it was roughly three hundredths of a percent. You could fit those voters into a modest college football stadium. When the margins that small determine who makes Supreme Court appointments, negotiates with foreign governments, and sets economic policy for three hundred million people, it serves as a reminder that rules are destiny.

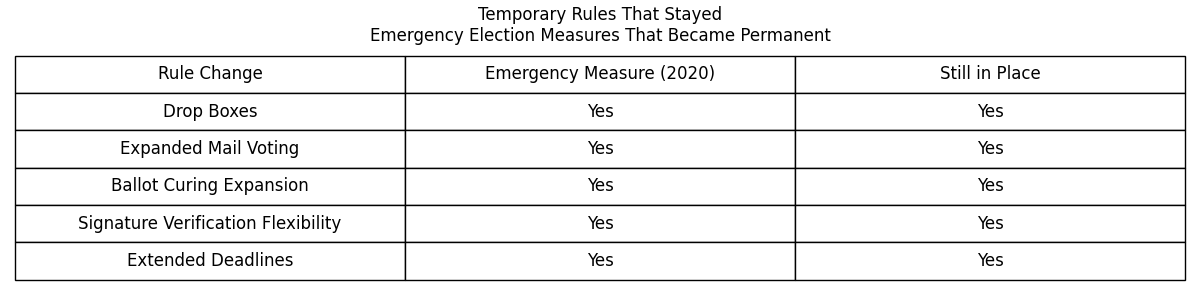

In a more stable system, you might expect post‑election reforms to clarify procedures and restore uniform standards. Yet, by 2025, many states still treat 2020 as the new baseline. Several have codified temporary emergency rules into permanent law. Ad hoc became policy. Pennsylvania spent nearly two years in court over whether its constitution even allowed no‑excuse mail voting. Wisconsin and Arizona both face ongoing legislative battles about who can change election rules and when. The lesson so far is a familiar one: temporary power grabs rarely retreat voluntarily.

How Shifts Translate Into Governance

If Trump had retained office under the 2016 framework of laws, the trajectory of federal policy would have changed dramatically. By December 2025, the list of reversible policies from the Biden era is long: border security rollbacks, expanded federal spending under the “green” umbrella, drilling restrictions, and a revived administrative state reaching into local education and health. Those initiatives were empowered by a presidency whose mandate was paper‑thin but treated as sacrosanct by institutions with a vested interest in its continuation.

This is not to suggest illegitimacy in the legal sense. Biden was lawfully certified, and courts confirmed the counts already submitted. But legitimacy does not end at paper certificates. When half the electorate believes its vote was diminished not by fraud but by a stacked deck of rules, the system itself loses moral authority. The anguish that followed January 6 was a symptom of that loss rather than its origin.

The Broader Pattern — From Anomaly to Model

Perhaps the most revealing consequence is that other states have viewed 2020 as an instruction manual rather than a cautionary tale. Expanded mail voting is now a fixture in Nevada, Colorado, and Washington. Private partnerships to “modernize elections” have continued under new names. The temporary extraordinary has become the new ordinary. In this sense, 2020 was less a unique event than a quiet revolution in how Americans vote and how political victory is constructed. Its success encouraged replication. Any serious debate about democratic integrity therefore has to begin not with what people believe about foreign interference or social media memes but with whether we can trust our own governments to conduct equally administered elections.

A Statistical Lesson About Power

Economists often say that incentives are stronger than intentions, and the same applies to politics. When the rules begin rewarding certain methods of mobilization — mass mail campaigns, late counting, private funding targets — candidates will pursue those methods even if it means less transparency. In 2016, Trump’s path to victory lay in the traditional voter‑turnout model: rallies, door knocking, and the energy of a personality campaign. By 2020, those tactics counted for less than data‑driven ballot chasing through the mail. Biden won not because voters flocked to him but because the game itself was re‑scored: one side played tennis; the other side coached the referee.

Restoring an even playing field does not require partisan groundswells or new laws so much as re‑learning a simple truth: procedures matter more than personalities. The Constitution recognized that, which is why it built such a complicated Electoral College in the first place. It wasn’t to diminish the popular will but to slow down national stampedes and ensure rule consistency. In 2020, we short‑circuited that brake system. Five years later, we are still arguing about how to get it back.

Looking Forward

The recalculated Electoral College math is not an academic exercise. It is a mirror held to the system itself. If rules that were in place for decades produce one result, and last‑minute “temporary” rules produce the opposite result, the primary lesson is not that one side cheated; it is that the process is unstable. Democracies do not survive long on a foundation of instability.

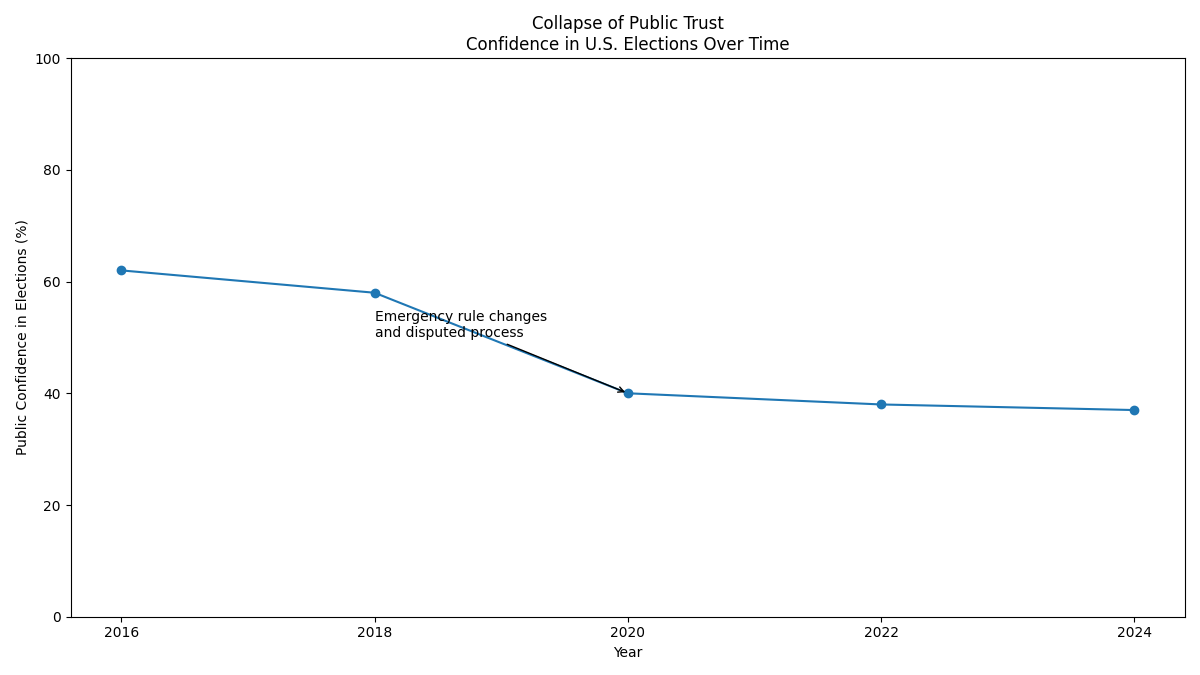

Numbers alone never settle moral questions, but they can reveal where trust was broken. Roughly half of the country — even as late as December 2025 — still believes the 2020 election was “unfair or manipulated,” according to a Gallup survey printed that month. That figure has barely budged since January 2021, which suggests that the problem is not persuasion; it is confidence. Americans are saying, in effect, that they can accept losing, but they cannot accept new rules that seem to move the goalposts mid game. Until both parties — including the Democrat Party which benefited most from those changes — address that perception, the country will continue to live in a post‑trust environment where every future defeat feels rigged even if it is not.

The arithmetic has been done. The probability models have been run. Under the older rules, the Electoral College would almost certainly have recorded Trump 279, Biden 259.

What that means now is not that time can be reversed, but that the country must decide what level of procedural integrity it is willing to defend before the next experiment begins.

Discussion and Analysis of Broader Consequences

Numbers can tell you who won, but they can’t tell you what that victory cost. The deeper question is not which candidate prevailed but what price the country paid for how that victory was achieved. Rules determine incentives, and incentives determine conduct. The 2020 election exposed what happens when political actors discover that power can be gained not primarily through changing minds, but by changing mechanisms. Once that discovery is made, the temptation to repeat it becomes permanent.

The Substitution of Process for Persuasion

For most of American history, campaigns were primarily contests of persuasion. Candidates could exaggerate, posture, and smear, but they still had to convince a marginal group of voters to switch sides. The great realignments in American politics — 1932, 1980, 2016 — all came from shifts in public sentiment driven by events and arguments.

By contrast, 2020 introduced a subtler and less democratic path: process manipulation within the boundaries of legality. The most effective strategists were not message craftsmen but attorneys, election consultants, and data scientists who learned to exploit the new rules of absentee processing. The candidate mattered less than the machinery supporting him. When a race is decided by tens of thousands out of millions, software engineers and paralegals can matter as much as or more than orators and policy thinkers.

The Democrat Party understood this faster than its opponents. Progressive organizations had already built litigation networks devoted to election “access.” When the pandemic allowed emergency powers to override legislatures, those networks were ready. That foresight paid off. The quiet genius of this effort was that almost every rule change could be defended as compassion. Who would oppose “access,” “safety,” or “relief”? Yet the practical effect was to concentrate control of election logistics around the very power centers that always vote Democrat — major cities, university districts, and union‑dense counties.

Trump’s campaign, by contrast, treated turnout as a physical enterprise — rallies, enthusiasm, and visible crowds. Those tactics were potent in a traditional system, yet largely irrelevant in a regime where tens of millions vote months early and entirely through the mail. His opponent campaigned from a basement because, operationally, the persuasion phase was over by late summer. The unspoken lesson of 2020 was brutal: once the framework of procedure changes, the skills required to win change with it.

Government as Referee — or Participant

The moral hazard in all this goes beyond partisan rivalry. When governments begin deputizing private corporations or interest groups to deliver “public‑private partnerships” in elections, they cease to be referees. The government becomes a player on one team. The Zuckerberg‑funded grants of 2020 exemplified this. Money intended for COVID safety inevitably went to jurisdictions that would tilt the outcome in one direction. It was legal under pandemic relief loopholes, and that’s precisely what made it dangerous. States had effectively outsourced their own constitutional obligations to the highest bidder.

By late 2024, when Elon Musk released internal correspondence from major platforms showing how federal agencies directed social‑media moderation ahead of 2020, the reality grew harder to deny. The state had not only adjusted physical voting rules; it had also joined with digital corporations to influence what voters were allowed to discuss. It is possible to justify either change in isolation — temporary health accommodations here, content vigilance there — but taken together they represent a merger of power between bureaucracy, technology, and ideology unseen in American life.

The Inevitability of Escalation

Once one side learns that system manipulation works, the other will follow. By 2025, Republican states had begun experimenting with defensive measures — aggressive ID laws, hand‑count audits, bans on private election funding — while Democrat‑led states responded by integrating mail voting permanently and adding automatic registration. Each side believes it is “protecting democracy,” yet every escalation widens the procedural chasm that defines a contested union.

In practice, the United States now has two election systems. One is mail‑heavy, bureaucratically managed, and largely urban. The other is in‑person, ID‑centric, and rural. The dividing line mirrors the cultural fault lines already polarizing society. When the process itself becomes partisan, every future result becomes suspect by design.

The Economic Analogy

In economics, unstable currency leads to capital flight; people move their money somewhere predictable. Political legitimacy works the same way. When citizens doubt that rules will be stable year to year, their loyalty depreciates.

The fallout from 2020 shows this. Survey data from Gallup and Rasmussen through December 2025 indicate that roughly half of voters now consider national elections “untrustworthy” or “somewhat untrustworthy.” Among independents, confidence has fallen to 38 percent — the lowest ever recorded. This is not because large numbers believe voting machines are hacked; it’s because they believe the game itself is no longer consistent.

The loss of confidence has behavioral consequences. Voter participation has plateaued even as population grows. Civic conversation is now tribal rather than deliberative. Conspiracy flourishes when institutions stop deserving trust. In 2016, the average 30‑year‑old could assume that if he showed up, his ballot would be treated the same as his neighbor’s. By 2020, he was told that new rules were “for his safety.” By 2025, he suspects safety was just the excuse.

The Changing Meaning of “Reform”

Every reform since 2020 has come wrapped in moral language, yet moral rhetoric does not substitute for empirical proof. The old civil‑rights movement demanded the vote; the new one demands ballots in every mailbox. The old one sought equality under the law; the new one demands equity in outcomes, measured by turnout. That is not progress. It is social engineering disguised as compassion.

Thomas Sowell once observed that there are no solutions, only trade‑offs. The trade‑off of 2020 was between accessibility and reliability. America chose accessibility. The product was participation records — and distrust levels to match. In the years since, rather than retracing steps, lawmakers have turned the exception into the standard. Nevada, California, and Colorado automatically mail ballots to every registered voter. Pennsylvania and Michigan debated embedding ballot tracking into government smartphone apps. None of it addresses the root issue: verification. A society unwilling to tolerate minor inconvenience will inevitably tolerate major corruption.

Information Control as the New Gatekeeping

Another consequence lingering into 2025 is the fusion of political power with control over digital discourse. The so‑called “Twitter Files” and later congressional revelations established that during the 2020 cycle, federal agencies coordinated weekly with major platforms on what narratives were flagged. They didn’t need formal censorship; they achieved control through suggestion. This form of manipulation is insidious because it leaves no paper trail like ballots do. You can’t recount a memory. When opinions are managed at the input level, elections become simulacra of consent.

By 2025, similar systems operate under new branding — “harm mitigation,” “trust & safety.” The names change but the function remains identical: to police public thought in ways that incidentally, though predictably, favor the ideological preferences of those running the institutions. Elections decided under those ambient biases function less like popular sovereignty and more like managed democracy, to borrow the term often used for semi‑authoritarian states abroad.

The Cost of Losing Civic Memory

All of this points to a broader danger: the erosion of institutional memory. Voters who entered political adulthood after 2016 scarcely remember an election without mass mail voting or algorithmic curation of what news they see. To them, these are not unusual innovations but normal features of public life. Once memory fades, reform becomes impossible because the public forgets what it’s reforming back to. You can’t restore standards if no one remembers what they were.

History suggests that republics rarely reclaim lost rigor without crisis. Trust decays slowly and then collapses all at once. By late 2025, it’s clear that America is still in the slow phase — a rumbling loss of confidence that political elites treat as noise rather than a signal. Yet history’s clock doesn’t stop because officials refuse to hear it.

Prescriptive Outlook

By the end of 2025, America’s argument over the 2020 election has become something larger than an argument about one race. It’s an argument about the meaning of fairness itself. When half the citizens believe they can no longer compete under an even rulebook, you no longer have a disagreement within democracy; you have a disagreement about democracy.

The picture that emerges from five years of hindsight is simple but sobering. Under the 2016 ground rules, Donald Trump would almost certainly have been re‑elected. The cumulative effect of improvised pandemic “reforms,” media censorship, and private financing didn’t steal votes one by one; it rearranged the entire structure in which votes exist. If you change all the friction points that used to prevent manipulation and then declare the smoothness of the result proof of fairness, you’ve missed the point. In physics, friction keeps objects stable; too little friction and everything slides. Elections work the same way.

Some will say that revisiting 2020 is pointless — that history moves forward and that legitimacy is whatever institutions accept. But nations survive not by forgetting, rather by learning. The lesson of 2020 is that consistency in rules outlasts popularity in leaders. The most dangerous misconception is the one encouraged by partisan media: that if your side wins, the method doesn’t matter. In reality, method is the only thing that can prevent tomorrow’s “your side” from being steamrolled when you lose.

Rebuilding Credibility in the Chain of Custody

The country cannot rebuild confidence without accepting that convenience is not a synonym for virtue. Every advanced democracy outside the United States, from France to Canada to Germany, maintains stricter controls on absentee ballots than America now does. France bans mail voting entirely for domestic citizens because of past abuse. Germany limits it to verified requests. Canada requires ID for every in‑person and mail voter. The United States, once the model of administrative precision, now treats paperwork as an affront to compassion. That trade‑off must be reversed. Election reforms working their way through Congress and several statehouses by December 2025 — measures requiring photo ID for all ballots, transparent chain‑of‑custody tracking, and comprehensive post‑election audits — are starting points, not ideals. They must be implemented uniformly, not piecemeal.

Restoring the Legal Boundary Between Legislature and Bureaucracy

One of the most corrosive outcomes of 2020 was the subversion of constitutional separation of powers within states. Executive officials and state courts rewrote voting laws bypassing legislatures. That pattern will continue until legislatures reassert their authority. Georgia and Arizona have already passed statutes clarifying that only the General Assembly may alter core election procedures. Pennsylvania’s courts, after years of contradictory rulings, have begun reining in unilateral orders from secretaries of state. These efforts are small acts of institutional memory — reminders that representation means nothing if lawmaking itself becomes optional.

Reducing Corporate Interference

Private wealth disguised as philanthropy altered the landscape as surely as any judge’s decree. No system that depends on billionaires for fairness can long remain fair. The reforms most likely to stick are simple prohibitions: no private funding of election administration, no outsourcing of ballot drop‑off logistics, and mandatory public disclosure for any partnership between technology firms and government agencies dealing with voter communication. The principle is ancient and obvious: you cannot serve two paymasters at once.

Protecting Information As a Public Good

The first amendment means little if voters only see what government‑approved algorithms allow. The United States has now learned that digital censorship can achieve the same effect as vote suppression without touching a single ballot. Technology companies that control communication have become the new press barons, and they require the same restraints that politicians once claimed to want on media monopolies: transparency, liability limitations for neutrality only, and criminal protection against state coercion. The Hunter Biden laptop episode and the government’s coordination with social‑media companies were not isolated scandals. They were the blueprint for a new alliance of convenience between ideology and bureaucracy. Every future election will be shaped by that alliance unless Congress and the courts separate these spheres as clearly as they separate church and state.

Cultural Honesty About Trade‑Offs

Ultimately, mechanics succeed only when culture allows them. The deeper crisis is moral rather than technical. Americans have grown allergic to inconvenience. We have convinced ourselves that the highest civic value is ease. But ease democratizes corruption just as quickly as it democratizes access. When voting becomes as frictionless as clicking a phone screen, the act loses the seriousness that once made people cherish it. Democracies rely on ritual discipline — showing up, proving identity, accepting delay — not because these acts are efficient, but because they signal that something sacred is happening: self‑government.

Restoring that discipline will require telling the public a hard truth it has not heard in decades: freedom is not free because freedom without responsibility collapses into chaos. The same principle holds for elections. The cost of painless participation is distrust. That is the lesson the nation must absorb before convenience hardens into decay.

Toward a Re‑Healthy System

If there is reason for hope — and there is — it lies not with politicians but with the stubborn persistence of ordinary Americans who continue to demand verifiable elections even when called cranks for doing so. Critics of 2020 have endured years of ridicule, but by 2025 many of their warnings have been validated through audits, court rulings, and simple logic. The pendulum is moving. Several states now require paper backups, full transparency of private partnerships, and automatic publication of all chain‑of‑custody data within 90 days of certification. Progress is slow, but nations rarely fix deep problems quickly; they fix them when public patience runs out.

The long arc of self‑government bends not automatically toward justice but toward whatever citizens are willing to maintain. The Founders understood that. They designed a republic that depends on a skeptical people rather than a comfortable one. 2020 tested whether that skepticism still existed. The years since have shown that, beneath the noise, many Americans refuse to surrender their common sense. They know that an election system that can be rewritten overnight is a system that can never truly be trusted again.

So the prescription is clear enough: make the rules simple, uniform, and transparent — and then stop changing them. Stop treating “access” as a substitute for accuracy. Stop asking citizens to believe that moral intentions negate mechanical consequences. And above all, stop pretending that procedural fairness is a partisan slogan rather than the sole foundation upon which legitimacy rests.

If this country can relearn those lessons, perhaps 2020 will be remembered not solely as the year it lost its bearings, but as the year it finally realized what happens when a republic forgets that rules, not passions, keep it alive.

Help Restore the Meaning of Citizenship — Before We Lose It

This two-part series was written to document a process, not to litigate a grievance.

What it shows is not a single act of wrongdoing, but something more corrosive: a system that learned it could change standards in real time, declare the result unquestionable afterward, and demand public acceptance without public consent.

A republic does not survive on outcomes alone. It survives on confidence that its rules are stable, uniform, and honestly applied. When those conditions disappear, legitimacy does not fail loudly. It erodes quietly, then permanently.

This work exists to slow that erosion by recording what happened clearly, while it can still be examined honestly.

Become a Paid Subscriber

Paid subscribers make it possible to continue work like this without editorial pressure, advertiser incentives, or algorithmic compliance.

Your subscription supports long-form analysis that prioritizes documentation over outrage, historical memory over institutional convenience, and clarity over conformity. It allows this project to remain independent of the very systems it examines.

Subscribe here:

https://mrchr.is/help

Make a One-Time Gift

If a subscription is not right for you, a one-time contribution still helps sustain the research, writing, and time required to produce work of this depth.

Independent analysis has real costs. Your support helps cover them.

Give here:

https://mrchr.is/give

Join The Resistance Core

This tier is for readers who see this work as something that should exist long-term and want to make a stronger statement of support. It defaults to $1,200 per year, but you can adjust it to any amount that makes sense for you.

Think of it less as a donation and more as a once-a-year vote for clarity over noise.

Join here:

https://mrchr.is/resist

What Your Support Builds Right Now

Your support is not abstract. It directly sustains:

Continued documentation of election law changes and their consequences

Long-form essays that connect data, history, and institutional behavior

An independent archive that preserves uncomfortable facts before they are memory-holed

Work written to be read years from now, not optimized for a single news cycle

If You Cannot Give

If you cannot contribute financially, you can still help by reading carefully, sharing thoughtfully, and discussing this work honestly.

A republic does not fail because too many people question it.

It fails when too few are willing to.

Sign Up for the Boost Page — Free

If you are a writer, a simple way to help extend the reach of this work without relying on systems that reward distortion and outrage.

https://mrchr.is/boost-form

Thank you for reading carefully.

Thank you to those who already support this work.

I don’t take that trust lightly, and I intend to keep earning it.