DC Authoritarianism? In 1962 the Pentagon Planned to Kill Americans

The same Washington that cries “tyranny” once tried to manufacture it.

In 1962, as Cold War tension gripped Washington, America’s top generals gathered in a windowless Pentagon office to discuss a plan that should never have existed. The idea was monstrous and straightforward at once: stage terrorist attacks against American citizens, sink refugee boats, even fake the hijacking of a civilian airliner, then blame it all on Fidel Castro to justify invading Cuba. The plan had a name, Operation Northwoods, and it carried the signatures of the highest-ranking officers in the U.S. military. It wasn’t a movie script or a rumor. It was an official memorandum of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, stamped and sent to the Secretary of Defense. And it came within one presidential signature of becoming real.

Today, the word authoritarianism gets thrown around in Washington like campaign confetti. A president threatens to send federal troops into a city wracked by violent crime, and headlines scream “dictatorship.” Senators hold hearings about “the rise of fascism” because law enforcement cleared a protest zone. The accusation has become political theater, loud, profitable, and detached from any sense of proportion. Yet six decades ago, real authoritarianism unfolded quietly in that same city, drafted not by populists or partisans but by men in uniform who believed the end justified the means. If we want to understand what tyranny actually looks like, we have to remember when it almost wore our own flag.

A Climate of Fear and Distrust

Real authoritarianism rarely begins with a dictator shouting from a balcony. It starts quietly, in meeting rooms, with officials who convince themselves that desperate times demand desperate measures. In 1962, those times felt very desperate. The United States and the Soviet Union possessed roughly 25,000 nuclear weapons between them, and each side believed the other might strike first. Newspaper headlines tracked missile tests the way sports fans track scores. For ordinary Americans, fear of annihilation was part of daily life; surveys from that year found that two-thirds of adults expected a world war within a decade.

That anxiety infected Washington. After the CIA’s failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, President John F. Kennedy’s relationship with his generals deteriorated. The military had trained more than a thousand Cuban exiles, promised them air cover, and watched the mission collapse in three days. To the Pentagon, Kennedy’s refusal to send American bombers to rescue the operation looked like weakness. To Kennedy, the fiasco proved that the intelligence community had misled him. Both sides left the episode humiliated and suspicious of the other.

Within weeks, the Kennedy administration launched Operation Mongoose, a covert program run by the CIA and the Pentagon to destabilize Castro’s government through sabotage, propaganda, and assassination plots. Hundreds of schemes were proposed, from poisoning cigars to exploding seashells near Castro’s favorite diving spots. The more each plan failed, the more reckless the next one became.

To the men drafting these ideas, Cuba wasn’t just another country; it was a symbol of credibility. The island sat ninety miles from Florida, well within the range of Soviet bombers. A single missile launch from Havana could reach Washington in under fifteen minutes. For generals raised in the shadow of Pearl Harbor, that proximity felt intolerable. The logic was simple: if the United States didn’t crush communism in its own hemisphere, no one would take its deterrence seriously.

At the time, nearly seventy percent of Americans supported military action against Cuba if it was found to be aiding Moscow. Newspapers ran headlines warning of “Red Missiles in the Caribbean.” The Pentagon’s budget had swollen to over $50 billion, the highest peacetime level in history. Fear paid well, and it justified everything.

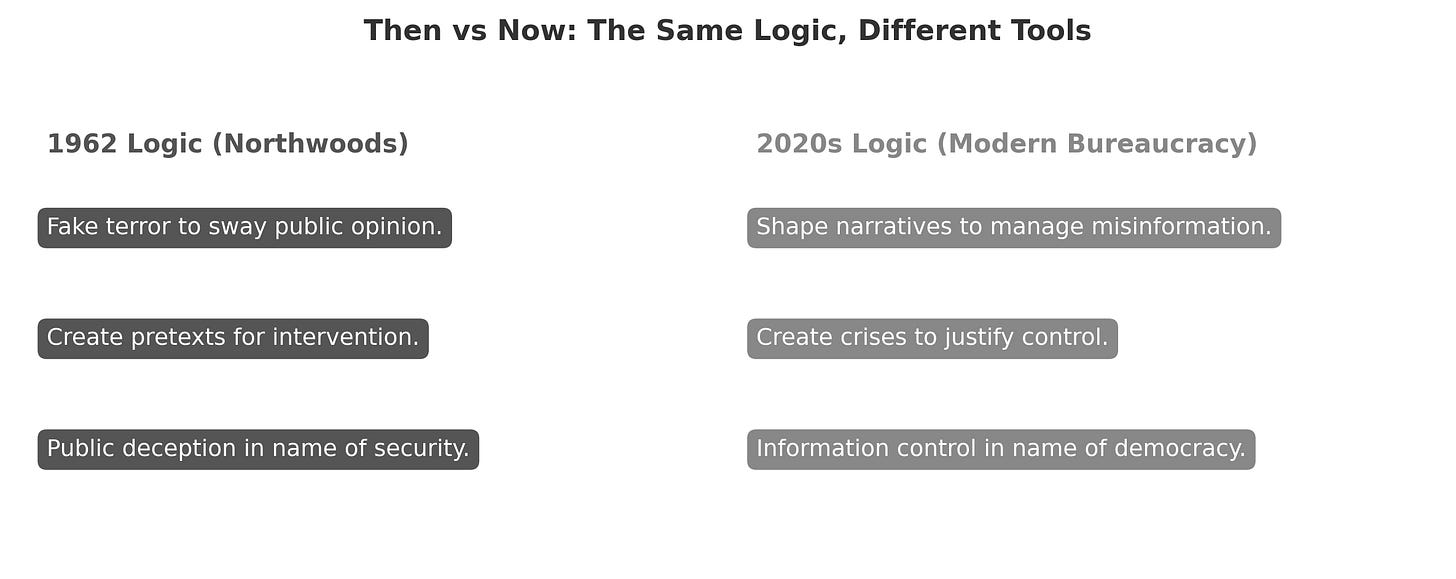

In that environment, the proposal to fake attacks on Americans didn’t seem insane. It seemed strategic. Every era finds a way to rationalize moral collapse as national security. In the early 1960s, the justification was stopping communism; today it might be fighting misinformation or protecting democracy. The language changes, but the impulse remains the same: when institutions fear losing control, they will cross lines they once claimed to defend.

Source: Annex to Appendix to Enclosure A, printed page 8, Joint Chiefs of Staff memorandum, 13 March 1962.

Operation Northwoods: A Plan for Manufactured Terror

On March 13, 1962, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, America’s highest-ranking military officers, sent a memorandum to Defense Secretary Robert McNamara titled “Justification for U.S. Military Intervention in Cuba.” It was nine pages long, stamped “Top Secret,” and signed by General Lyman Lemnitzer, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs. The document did not suggest a defensive strategy or a rescue plan. It proposed staging violent acts against the United States and blaming them on Cuba to create public outrage strong enough to justify war.

The language was clinical, the morality chilling. It described “a series of well-coordinated incidents” designed to convince both the American people and the international community that Cuba was the aggressor. It even detailed how to manipulate the news cycle, recommending that “casualty lists in U.S. newspapers would cause a helpful wave of national indignation.” The word helpful appeared in a context that referred to the deaths of Americans.

The proposals varied in scale but shared one goal: shock the public into demanding retaliation. The document suggested blowing up a U.S. Navy ship in Guantanamo Bay, staging funerals for the supposed victims, and then broadcasting that “Communist Cuban forces” had attacked. It proposed staging hijackings of commercial airliners, or substituting a drone aircraft for a passenger jet and claiming it was shot down. It suggested sabotaging a U.S. military base or planting explosives in American cities, possibly in Florida or Washington, and “discovering” Cuban involvement afterward. It even outlined plans to fabricate attacks on Cuban refugees, sinking boats filled with migrants, and blaming it on Castro’s navy.

At the time, creating “pretexts” for war was not a new idea. The Spanish-American War followed the mysterious explosion of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor, an incident that the press blamed on Spain before evidence pointed to an accident. The Gleiwitz Incident of 1939 had been a fake Polish attack orchestrated by Nazi Germany to justify invading Poland. Northwoods fit that same historical pattern: when public support for war does not exist, invent an event that creates it.

What made this episode unique was how open and formal it was. The memo was typed on Department of Defense letterhead, circulated among top officials, and stored in official archives. Its existence was confirmed when it was declassified in the late 1990s as part of the John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act and published by the National Security Archive in 2001. Historian James Bamford, in his book Body of Secrets, called it “the most corrupt plan ever created by the U.S. government.”

Perhaps the most disturbing truth is that nothing in the document sounds extreme in its own bureaucratic context. It reads like any other interagency memo: calm, precise, and procedural. The machinery of government can disguise evil as efficiency. The same institution that built the interstate highway system and put men on the moon had officers within it calmly suggesting mass deception to steer the public toward war.

Kennedy’s Rejection and the Breaking Point

When Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara read the proposal, he dismissed it immediately. According to later accounts, he was shocked that such an idea had reached his desk. When briefed, President Kennedy was furious. To him, it was moral insanity, a betrayal of every democratic principle he had sworn to uphold.

That rejection deepened an already growing rift between Kennedy and his generals. They viewed him as hesitant and inexperienced; he saw them as reckless and consumed by Cold War zeal. The same officers who signed Northwoods had urged airstrikes and even nuclear confrontation during earlier crises. One, Air Force General Curtis LeMay, told Kennedy that avoiding war with the Soviets would be “worse than appeasement at Munich.” Kennedy disagreed, and his decision probably saved the world.

Within months, General Lemnitzer was reassigned to Europe as Supreme Allied Commander of NATO. It was a polite demotion, but everyone understood the meaning. Kennedy replaced him with General Maxwell Taylor, who shared his view that military action should serve policy, not dictate it.

That divide came to a head during the Cuban Missile Crisis later that same year. When reconnaissance photos revealed Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba, Kennedy’s generals again pushed for airstrikes and invasion. Instead, Kennedy ordered a naval blockade and opened secret negotiations with Moscow. The standoff ended without a single shot being fired. The military saw caution; history saw restraint.

After the crisis, Kennedy’s distrust of the national security establishment only grew. He spoke openly about reorganizing the CIA and placing covert operations under tighter civilian control. He told one aide he wanted to “splinter the CIA into a thousand pieces and scatter it to the winds.” Whether or not he could have achieved that remains unknown, but the statement itself revealed how shaken he was by what he had learned behind closed doors.

By the time Kennedy traveled to Dallas in November 1963, his relationship with the defense and intelligence community had collapsed. Whether that tension had any connection to his assassination remains a matter of speculation, but the record of Operation Northwoods proves that mistrust between the Commander-in-Chief and his own military was not imaginary. It was earned.

The Pattern of Power

Every bureaucracy has a survival instinct. It may speak in the language of service or security, but its first loyalty is almost always to itself. Operation Northwoods was not an accident of history; it was a perfect expression of that instinct. The generals who drafted it were not seeking chaos. They were seeking control, control of outcomes, of narratives, and of public emotion. When they could not persuade the President to act, they looked for ways to convince the public instead.

This pattern appears throughout history. In 1939, German officers staged the Gleiwitz Incident, a fake Polish attack on a German radio tower, to justify invading Poland. In 1898, the explosion of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor created the rallying cry “Remember the Maine,” leading to war with Spain, even though later evidence showed the blast was likely accidental. In both cases, power needed a story more than it needed truth. Northwoods followed that same logic: create the story first, and the people will follow.

Large institutions drift toward this mindset because accountability is their natural enemy. The military, the intelligence community, and even the modern administrative state all depend on secrecy to function. But secrecy that lasts too long turns inward. It stops protecting the nation and starts protecting the institution. During the Cold War, the United States built a system that could launch a nuclear strike in minutes, but it could not restrain its own covert programs without a direct order from the President. The lesson of Northwoods is that moral checks only work when they are enforced by individuals who remember why those checks exist.

The same bureaucratic reflex can be seen in other moments of American overreach. The Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964, which led Congress to authorize full-scale war in Vietnam, was later revealed to be based on distorted intelligence. The COINTELPRO program of the FBI in the 1960s and 1970s targeted civil rights leaders and anti-war activists under the banner of “national security.” In each case, institutions believed their mission justified bending the law or the truth. Once those actions were exposed, they were dismissed as “excesses” or “mistakes,” but the machinery that produced them remained intact.

It is easy to believe that democracy protects itself. It does not. It depends on people's willingness to say no when saying yes would be easier. Kennedy’s rejection of Northwoods mattered not only because it stopped a plan but because it set a precedent. It reminded a restless military establishment that in the United States, the generals answer to civilians, not the other way around. Yet the instinct to preserve power never disappears. It adapts, rebranding itself with new language, national security, misinformation, or public safety, but always keeping the same goal: control over perception.

Understanding Northwoods means understanding that authoritarianism does not require a dictator. It requires an institution that convinces itself it is too important to be questioned.

Fast-Forward to Today

When Americans hear the word authoritarianism today, it is usually in a partisan context. The word appears in headlines, congressional hearings, and campaign speeches. It is used to describe border enforcement, crowd control, social media regulation, and nearly every presidential policy that offends a rival faction. Yet few stop to ask what authoritarianism actually looks like in practice. It is not the presence of soldiers in the streets; it is the absence of restraint in the minds of those who command them.

Over the past decade, Washington has redefined strength and weakness according to political convenience. When federal agents protected a courthouse during riots, commentators called it fascism. When city governments ordered mass lockdowns that kept citizens indoors for months, they called it public health. The same people who now warn that sending the National Guard into violent neighborhoods is “authoritarian” rarely objected when intelligence agencies were monitoring journalists, censoring information, or labeling political dissent as extremism. Power exercised by their side is always protection; power exercised by the other side is always tyranny.

That double standard is not new. It is the natural language of institutions that see themselves as moral gatekeepers rather than servants. During the Cold War, the same mindset led generals to believe that deception and violence were justified to “protect democracy.” Today it convinces bureaucrats and politicians that censorship and selective law enforcement are warranted for the same reason. The tools have changed, from covert operations to algorithms, from bombs to narratives, but the impulse remains the same. When control of information replaces persuasion, and when policy is justified by fear rather than principle, the line between democracy and authoritarianism begins to blur.

Consider the contrast. In 1962, senior military officers plotted to kill Americans to create outrage that would enable war. In 2025, political commentators declare tyranny when a president suggests sending federal forces to stop actual violence in cities like Chicago or Washington, D.C. One is hypothetical power used responsibly to prevent chaos; the other was real power almost used immorally to cause it. The difference lies not in strength but in integrity. The generals of Operation Northwoods believed they could manipulate the public for its own good. Modern partisans believe they can manipulate the definition of tyranny for their own.

What both eras share is a refusal to confront hypocrisy. Americans prefer their authoritarianism abstract, something that happens in textbooks or foreign capitals. But history shows that when fear and self-interest converge, any government can rationalize the unthinkable. The danger is not in soldiers following lawful orders; it is in leaders, editors, and bureaucrats who convince themselves that the ends justify the means. That was the logic behind Operation Northwoods. It remains the logic behind much of Washington today.

Why Hard Truths Get Forgotten

The story of Operation Northwoods should have become a national scandal. It should have forced hearings, firings, and reforms. Instead, it vanished into classified archives for more than thirty years. When the file was finally released in the late 1990s, it made a few headlines, inspired a handful of documentaries, and then faded again. Even today, most Americans have never heard of it. That silence says as much about the nation’s psychology as it does about its politics.

People do not like to believe that their government is capable of plotting harm against them. It violates a basic emotional contract between the citizen and the state. The easier response is to look away, to treat the incident as an anomaly, or to label anyone who remembers it as paranoid. The result is that real abuses of power are forgotten, while imagined ones dominate the news. The country can debate tweets for weeks but cannot recall a declassified plan to kill Americans for propaganda value.

There are structural reasons for that amnesia. In the United States, the average news cycle lasts about forty-eight hours. Public attention shifts with each headline. In that environment, scandals without arrests or trials simply evaporate. Operation Northwoods never produced a court case or a dramatic confrontation. No one was punished. No one was even reprimanded. Bureaucracies prefer quiet corrections to public accountability, and the press often follows their lead. The incentive to move on is stronger than the incentive to understand.

There is also a cultural dimension. Americans prefer redemption stories to cautionary tales. The idea that the same country that won World War II could have planned a false-flag operation against its own citizens is too uncomfortable to fit within the national myth. It forces people to confront the reality that power, even in a democracy, can rot from within. Most would rather believe that such behavior belongs to other nations, to dictatorships, not to us.

That selective memory has consequences. It allows the same logic to resurface under new names and in new forms. The willingness to deceive for a “greater good” reappears in surveillance programs, covert funding of media outlets, and selective censorship of political speech. Each generation assumes it has learned from the past while repeating its mistakes more subtly. The tools change, but the moral math remains the same: if the outcome feels noble, the method can be excused.

Remembering Operation Northwoods is uncomfortable, but forgetting it is dangerous. When citizens no longer recall how far their leaders were once willing to go, they become easier to persuade that “this time” will be different. History suggests it rarely is. Truth must be remembered precisely because it is inconvenient. The harder a fact is to accept, the more essential it becomes to preserve.

Then vs. Now: The Lesson That Still Matters

In 1962, Washington’s most powerful generals planned a deception that would have rewritten history. They believed their intentions were patriotic. They believed they were protecting the nation. In truth, they were preparing to destroy the trust that holds a nation together. When Kennedy refused their plan, he did more than reject a military operation. He reaffirmed that power must answer to conscience.

Today, the word authoritarianism has become a buzzword in political debate. A president deploys federal officers to restore order, and the media call it tyranny. The same voices that denounce “militarization” demand censorship of opposing speech. The result is a culture that fears the wrong kind of power. We panic at uniforms while applauding control. We call strength a threat and submission a virtue.

The real lesson of Operation Northwoods is not that America once flirted with authoritarianism, it’s that it did so in silence. The plan was written, stamped, and hidden. No tanks rolled, no speeches thundered. It happened in the calm of bureaucracy, and it was almost forgotten. That is how freedom erodes: not with violence, but with paperwork.

If Americans wish to guard against tyranny, they must learn to recognize it. It is not lawful force used to restore peace. It is unlawful deceit used to manufacture consent. In 1962, Washington planned to fake terror to justify war. In 2025, it calls the prevention of terror authoritarianism. That reversal shows how far moral clarity has fallen.

Remembering Operation Northwoods is not cynicism. It is civic hygiene. Freedom survives only where truth is remembered. Power still seeks permission to protect itself. The only question is whether anyone in our time will have the courage to say no.

Why This Work Must Continue

The danger of Operation Northwoods was not just in what it proposed, but in how easily it could have happened. The paper trail of deceit was stamped, signed, and nearly executed, all in the name of “security.” That kind of power still exists, and it still wears the mask of good intentions.

That’s why I write. Not to stir paranoia, but to document truth before it disappears beneath revision and denial. Every essay, every investigation, every chart is a defense against the slow normalization of deceit. The writing is free to read, but the work behind it is not free to produce. Truth doesn’t fund itself, and the people who fear it will never fund it for us.

If you believe this fight matters, if you believe truth should be remembered before it’s erased, here’s how you can help keep it alive:

Become a Paid Subscriber today.

Show them that history can’t be buried and that silence will never win.

https://mrchr.is/help

Are you in a position to do more?

Then become part of the foundation that keeps this movement standing.

Help me build what truth deserves, something lasting.

https://mrchr.is/resist

Not ready for that step, but still want to help?

You can still keep the lights on and the mission alive.

https://mrchr.is/give

This isn’t just a publication anymore. It’s becoming a movement, a nonprofit built to train the next generation of writers, researchers, and truth-tellers who will carry this mission forward when others stay silent. But to build it right, I need more than readers. I need allies. I need builders.

If you still believe truth matters, if you still hear that quiet warning in the pages of our own history, then stand with me. Help make sure the next Operation Northwoods never gets written.

Great article, and sound warnings. The article is about 50% too long, however. It repeats itself several times. Keep up the great work from a refreshing perspective.

Spot on in your analysis. Really makes me question our invasion of Iraq in 2003. Quiet governmental authoritarianism. Scary!