Press 2 for Enslavement: Why the Democrat Party Prefers You Never Learn English

Democrats turn language barriers into political leverage over non-English voters

“Whoever controls your language, controls you.”

The Economics of Control

Language is the first unit of human capital. An individual who commands the language of his country commands his own choices. An individual who does not must rent that control from others. The claim of this analysis is straightforward: the Democrat Party derives a political benefit when a significant number of residents remain limited in their command of English. A status of “Limited English Proficiency,” or LEP, means a person speaks another language at home and reports their English skill as less than “very well.” According to the U.S. Census Bureau, more than 25 million people fall into this category nationwide, creating a vast and politically valuable constituency. This status transforms routine civic life, from reading mail to filling out a ballot, into a series of transactions that require intermediaries.

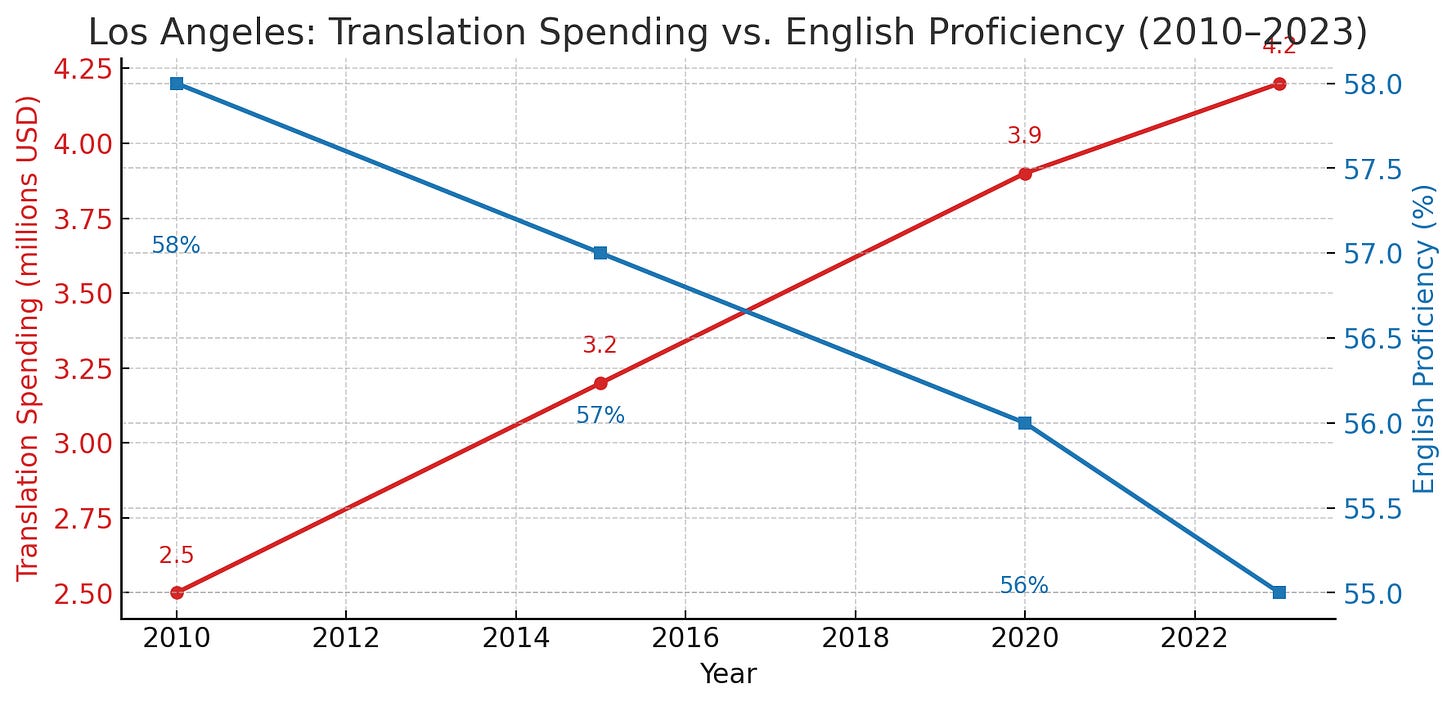

These intermediaries, whether they are translators, nonprofit navigators, or community organizers, become gatekeepers. Gatekeepers, in turn, acquire budgets, build payrolls, and cultivate political loyalties. The process is often referred to as “inclusion” or “compassion.” The measurable result is dependency. The method is not difficult to recognize. One must build a permanent translator economy, keep official texts complex, and measure success by the number of “people reached” rather than the number of people who no longer require assistance. In a system designed to promote independence, spending on translation services would decrease as English proficiency increases. When both climb together, the product is not freedom. It is management.

The Architecture of Dependency

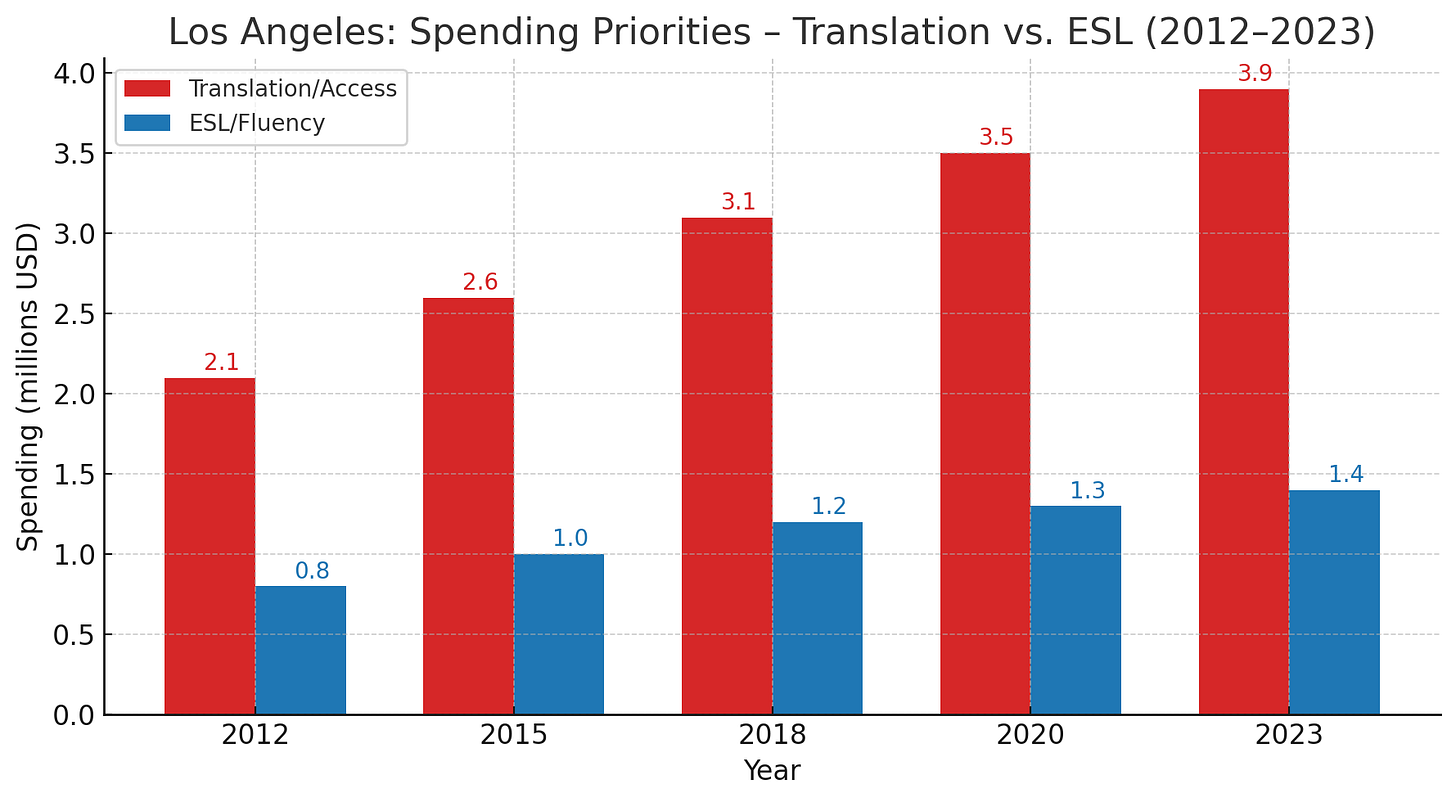

An examination of the incentives and machinery in a city like Los Angeles reveals how this system of management is constructed. The city treats language access not as a temporary bridge, but as a permanent and expanding line of business. The City of Los Angeles reported spending approximately 3.9 million dollars in a single year for interpretation, translation, outreach, and related staff costs. This is not an anomaly; it is a standing operational expense designed to service a large and growing population. In Los Angeles County, census data indicates that nearly half of all residents speak a language other than English at home, and a substantial portion of that group, numbering in the hundreds of thousands, meets the LEP definition.

The system is engineered for continuity and ease of use. The City Clerk maintains multi-year master agreements with a roster of translation and interpreting firms, with many contracts carrying six-figure ceilings through 2027. These agreements allow city departments to order language services quickly for anything from public health notices to housing applications, turning what could be discrete purchases into routine, ongoing consumption. When a service has a standing vendor bench and easy ordering, its use naturally expands, creating a self-perpetuating constituency of providers who have a vested interest in the system’s continuation.

A network of nonprofit organizations reinforces this commercial layer. The City funds a network of FamilySource Centers, operated by outside community-based organizations, at a cost of roughly $750,000 per site. These centers are not merely translation vendors; they are community intermediaries that interact with the same households, often in the same languages, on a weekly basis. Their success is measured by throughput: the number of people served, workshops held, and materials distributed. It is not measured by the number of residents who achieve English fluency and no longer require their services, a metric conspicuously absent from their public reports.

This ecosystem finds its political application during election season. Los Angeles County conducts its elections in eighteen languages and purchases pre-election voter “education and outreach” in those same language markets, with recent expenditures running into the low seven figures. These publicly funded campaigns prime the very audiences that political operations will target weeks later. The informational and persuasive messages travel along the same well-funded channels, creating a seamless transition from “nonpartisan” government outreach to partisan political mobilization.

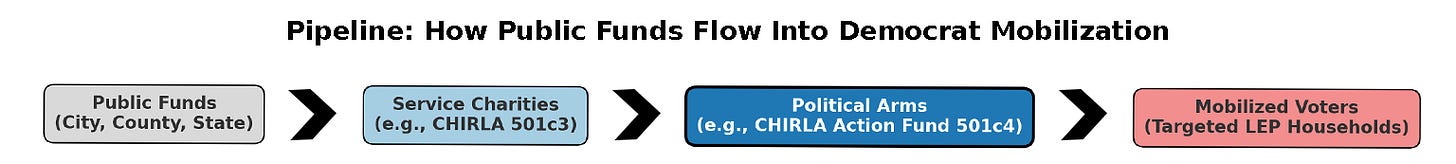

The political alignment is unmistakable. A service charity like the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights (CHIRLA), a 501(c)(3) organization, provides services to immigrant and LEP households year-round. It shares a street address and a brand with the CHIRLA Action Fund, a 501(c)(4) political organization that endorses candidates, such as Mayor Karen Bass and other local Democrats, and runs get-out-the-vote drives in the same neighborhoods. The charity, often benefiting from public support, builds trust and cultivates lists. The political arm activates that trust and those lists when ballots arrive. The structure is legal, but the result is a seamless pipeline from public services to political mobilization, a pipeline that flows overwhelmingly to the benefit of the Democrat Party.

An Examination of Common Objections

The defenders of this system rely on a set of predictable rhetorical claims. When examined against the facts, these claims reveal more about the system’s priorities than its compassion.

One common claim is that “translation is inclusion.” Yet inclusion that does not lead to progression is merely a holding pattern. If the system’s goal were genuine inclusion, one would expect to see translation expenditures fall as English proficiency rises. Instead, the data from Los Angeles show the opposite: spending on translation services and the volume of translated materials are rising, indicating that the need for intermediaries is being serviced, not solved. The growth of the LEP population in the region over the past decade, despite millions spent on “access,” confirms that the system is managing a condition rather than curing it.

Another argument is that “people are learning, it just takes time.” While adult English programs do exist and serve tens of thousands of individuals, their capacity is dwarfed by the hundreds of thousands of LEP residents in the county. Reports from the Los Angeles Community College District often highlight long waiting lists for English as a Second Language (ESL) courses. More importantly, public reporting on these programs emphasizes inputs, such as enrollments and hours, not outcomes. If the system were serious about fluency, it would publish quarterly data on the number of adults who verifiably exit LEP status. That number remains conspicuously absent from the headlines of official reports.

It is also claimed that these services are “nonpartisan.” However, services build audiences that politics then mobilizes. The publicly funded “voter education” campaigns run by Los Angeles County appear in the same ethnic media outlets that carry partisan campaign ads weeks later. An analysis of these media buys often reveals that the outlets receiving government funds have a clear and established history of endorsing Democrat candidates. The audience, the language, and the timing align. The political advantage flows directly to the party with the larger and better-funded field machine in those communities, which in Los Angeles is the Democrats.

Finally, some will argue that the relationship between service charities and their political arms is legal and proper. While the separation between a 501(c)(3) and a 501(c)(4) is legal on paper, in practice they often share a brand, an address, and a constituency. This dual-entity structure is a common feature of the modern political landscape, used effectively by organizations to leverage publicly subsidized service delivery for political gain. The pipeline from publicly supported services to political turnout does not need to be illegal to be effective. Incentives, not conspiracies, drive the outcome.

A Blueprint for Actual Independence

A system that genuinely sought to foster independence would be structured very differently. Its incentives would reward exits, not throughput. Such a system is not theoretical; it can be constructed with a series of clear, measurable policies that align economic incentives with the goal of emancipation.

First, public contracts for language services should be tied to verified outcomes. Instead of paying vendors and nonprofits for services delivered, payment should be linked to the number of residents who verifiably exit Limited English Proficiency. A vendor would earn a base rate for enrollment, but a significant bonus only when learners achieve tested proficiency milestones. This introduces a direct financial incentive for providers to produce tangible results.

Second, the metrics must change. A simple, public scoreboard should be published quarterly, showing four key numbers for each district: language-access spending, English as a Second Language (ESL) seats delivered, tested proficiency gains, and exits from LEP. When the public can see whether dollars are buying independence or merely mediation, accountability becomes possible and the cost-benefit of different approaches becomes clear.

Third, the budget must respond to results. As tested English proficiency rises in a given zip code, the following year’s budget allocation for translation services in that area should automatically decrease. This creates a direct incentive for the system to succeed in its stated mission of fostering fluency, as success would be rewarded with fiscal efficiency rather than perpetual budget growth.

Fourth, the civic text itself must be fixed before it is translated. Ballots and official forms, which often read like legal contracts, should be required to include a plain-English summary written at an eighth-grade level, along with a simple, one-sentence box that clearly states the effect of a “yes” or “no” vote. This would reduce the need for intermediaries for native and non-native speakers alike, lowering costs and increasing direct civic engagement.

Finally, visible firewalls must be established between publicly supported service charities and their political counterparts. When a 501(c)(3) organization receiving public funds shares an address or leadership with a 501(c)(4) active in local races, it should be required to maintain and publicly document separate staff, separate lists, and separate accounting. Subsidized services must not be allowed to directly feed a political machine.

Management versus Emancipation

Incentives, not intentions, determine outcomes. A system that is paid to translate in perpetuity will translate in perpetuity. Programs that cannot demonstrate that they are reducing the need for their own existence are not bridges to independence. They are businesses, and in this case, politically useful ones. The economic reality is that English proficiency is one of the most significant factors in upward mobility for immigrants. Yet the system in place creates a powerful disincentive for the political class to solve the very problem they claim to be addressing.

The effect on civic life is quiet but decisive. A voter who cannot understand a ballot without assistance does not truly own his choice; he rents it from the helper. In a city like Los Angeles, this network of helpers is funded year-round, primed with “informational” dollars during election season, and then activated by the political campaigns of the Democrat Party. This creates a dependent voting bloc that is insulated from direct engagement with a broader range of political ideas.

This is not a system born of compassion. Help that leads to independence is help. Help that never ends is management. The test is simple. If the number of people who no longer need your assistance is not rising, you are not helping. You are managing. The data from Los Angeles and other cities run by Democrats indicate a clear choice has been made. They have chosen to manage a dependent constituency rather than foster an independent citizenry.

This is Where Reflection Replaces Deflection

If language is control, then truth is emancipation. Reading is the start. Supporting is the step that turns independence from a wish into a weapon.

Step Up: Become a Paid Subscriber: Support the work that tells uncomfortable truths.

Join the Core: Fund This Mission: Become a foundational partner in the fight for reality.

Make a One-Time Contribution: Fuel the work of accountability with a one-time gift.

Arm Someone With the Truth: Give a Gift Subscription: Don’t just face the truth. Share it.

Like a stable of whores for votes.

What a visible unveiling of the LEP (voting) issue in LA and the rest of the country. Great research and, as always, writing. Don’t stop, please.