Six Degrees of Desperation

How a Society Is Softened, Managed, and Made Irreversible

Desperation does not announce itself. It settles in.

Societies do not surrender freedom because they are persuaded to do so. They surrender it because, over time, ordinary people begin to feel that every available option costs too much, takes too long, or carries too much risk. That condition has a name. It is desperation.

Desperation is not panic. It is not chaos. It is not collapse. It is the slow normalization of stress, insecurity, and resignation. Life continues on the surface. People go to work. Children go to school. Elections still happen. The language of rights and freedom remains intact. What changes is what people are willing to tolerate, and what they stop expecting from the future.

If you want to understand why societies decline, start with a simple question: can the average person still plan? Not fantasize, not speculate, just plan. Can he reasonably expect that hard work will produce stability, that honesty will not ruin him, and that the rules will be applied in something resembling a consistent way?

When the answer becomes no, societies do not always rebel. More often, they adapt downward. Expectations shrink. Time horizons shorten. Principles that once felt obvious begin to feel impractical. What used to be considered temporary hardship becomes the background condition of life.

This is why modern decline confuses comfortable people. They look for dramatic signs, as if freedom is lost in a single event. But in real life, freedom is lost the way savings are lost: not in one purchase, but in a long series of small withdrawals, each justified by immediate need.

As pressure accumulates, people stop thinking in decades and start thinking in weeks. They become cautious rather than ambitious, defensive rather than hopeful. Survival instincts replace civic instincts. That shift happens quietly, without announcements or declarations.

At the same time, the information environment changes. It becomes saturated, contradictory, and weaponized. People are told, often in the same week, that the system is illegitimate and that questioning it is dangerous. A healthy society can survive disagreement. It cannot survive a permanent assault on shared reality.

Six Degrees of Desperation is a description of how a population is softened without being conquered. Each degree feels manageable. Each adjustment feels rational. No single step feels decisive.

Destabilize → Divide → Demoralize → Depend → De-platform → Destroy

The early stages make life more complicated to plan. The middle stages isolate and exhaust. The later stages reward compliance and punish speech. The final stage removes the memory that things ever worked differently.

This is not a story about villains. It is a story about incentives, exhaustion, and adaptation. It explains how citizens become clients, and how clients eventually become quiet spectators.

Once desperation becomes normal, relief begins to feel like freedom. And by the time people realize what has been lost, they often no longer remember how recovery would even look.

That is where the six degrees begin.

Destabilize

Create permanent insecurity that prevents long-term thinking

A society does not begin to unravel when people become poor. It begins to unravel when people can no longer plan.

For most of the twentieth century, the central stabilizing feature of American life was not prosperity in the abstract, but predictability. A person who worked steadily, avoided obvious self-destruction, and exercised basic prudence could reasonably expect his life to improve over time. That expectation allowed people to think in decades rather than months. It anchored families, communities, and institutions.

Destabilization begins when that expectation quietly breaks.

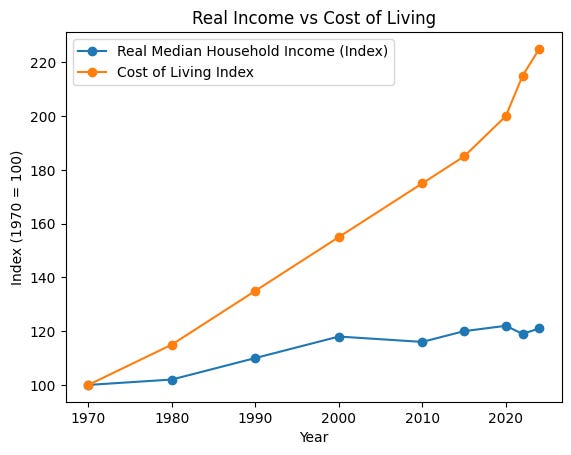

By the early 2020s, the economic math facing ordinary households had changed in ways that were both sudden and cumulative. Inflation accelerated sharply after 2021, reaching levels not seen since the late 1970s. Even after inflation rates moderated, prices did not return to previous levels. For households, that distinction mattered far more than any headline number. The cost of food, energy, insurance, and basic services remained permanently higher.

Housing amplified the effect. Between 2020 and 2024, home prices rose far faster than median incomes in most regions of the country. At the same time, mortgage rates more than doubled from their pandemic lows. The combination pushed monthly payments beyond the reach of many first-time buyers, even those with stable employment. This was not confined to coastal markets. Smaller cities and suburban areas followed the same pattern, only with lower absolute prices and the same affordability problem.

Ownership matters because it creates continuity. It ties effort today to security tomorrow. When ownership moves out of reach, people do not merely feel poorer. They feel untethered. Renting becomes not a temporary stage, but a permanent condition. Mobility declines. Dependence increases.

The labor market offered little relief. Official unemployment figures often appeared strong, but they masked rising underemployment, job churn, and fragile work arrangements. Many workers were employed but unable to advance, unable to save, and one disruption away from serious trouble. The gig economy did not replace stability. It replaced predictability with flexibility, which sounds attractive until flexibility becomes compulsory.

This is where older measures like the Misery Index still offer insight. The classic index simply adds inflation and unemployment, and even by that narrow definition, periods of elevated inflation have historically coincided with political and social stress. But the modern experience of misery extends beyond those two variables. By the mid-2020s, households were facing high costs across housing, healthcare, education, childcare, and interest payments simultaneously. Each category reinforced the others.

The behavioral effects were predictable. Time horizons shortened. People delayed marriage, children, relocation, and entrepreneurship. Risk became intolerable, not because ambition disappeared, but because failure carried harsher consequences. When one mistake can mean losing housing or healthcare, caution becomes rational.

Destabilization also works because it lacks a clear villain. Inflation is attributed to global forces. Housing shortages are blamed on abstract supply constraints. Energy prices are tied to geopolitics. Each explanation may be partially true, but together they create a sense that nothing can be fixed quickly and no one is accountable. That perception discourages collective action. People adapt individually instead.

This is not how collapse looks. In a collapse, hardship is obvious and often temporary. In destabilization, hardship becomes ambient. It fades into the background of daily life. People stop saying that things are broken and start saying that things are just hard now.

There is a generational dimension that cannot be ignored. Younger adults who entered the workforce after the 2008 financial crisis and then lived through the pandemic disruptions experienced instability as a baseline rather than an exception. Many never saw the period of broad wage growth and affordable housing that earlier generations assumed was normal. When instability is normalized early, expectations adjust downward permanently.

This matters politically because people who cannot plan are easier to manage. Long-term commitments require confidence that sacrifice will be rewarded. When that confidence disappears, people stop defending systems that promise future benefit and start looking for immediate relief.

Destabilization does not radicalize people at first. It exhausts them. It drains the energy required to argue, organize, and resist. It nudges people toward pragmatism, which in this context means choosing whatever reduces immediate stress, even if it increases long-term dependence.

Historically, societies have endured hardship when people believed it was temporary and shared. They struggle when hardship feels permanent and individualized. Destabilization creates exactly that condition.

A society that cannot plan is not yet controlled. But it has been prepared.

The next degree determines whether that preparation produces solidarity or isolation.

Divide

Ensure hardship is faced alone

Economic stress does not automatically produce social fracture. That only happens when people stop believing they are facing hardship together.

Division is often described as disagreement, but disagreement is not the problem. Democratic societies have always disagreed. Division becomes corrosive when differences are moralized and when shared citizenship is replaced by suspicion. At that point, people do not simply argue. They retreat.

By the mid to late 2010s, and accelerating into the 2020s, political disagreement in the United States increasingly took this form. Polling consistently showed rising levels of partisan animosity, with growing numbers of Americans viewing those on the other side not merely as wrong, but as dangerous. This mattered less for elections than for everyday life. It changed how people interacted at work, at home, and in their communities.

Withdrawal became a rational response.

Many people learned that speaking honestly carried social costs. Conversations that once involved disagreement now carried the risk of permanent rupture. As a result, people avoided topics altogether. They stopped testing ideas. They stopped asking questions. They maintained surface harmony at the expense of trust.

This withdrawal showed up most clearly in institutions that once absorbed conflict. Families avoided sensitive discussions. Workplaces adopted formal and informal norms that discouraged dissent. Civic organizations narrowed their missions or disappeared. The spaces where people once learned to disagree productively shrank.

Social media intensified this dynamic by rewarding moral certainty and punishing ambiguity. The loudest voices tended to be the most extreme, which created a distorted sense of consensus. Moderation looked like weakness. Nuance looked like evasion. Many people who held mixed or cautious views chose disengagement over participation. The public square did not empty, but it thinned.

Division deepens desperation by stripping away informal support. Economic pressure alone does not isolate people. Social fracture does. A person struggling financially but embedded in a network of friends, family, and community still has buffers. A person facing the same stress while believing that neighbors, coworkers, and even relatives are potential adversaries does not.

This isolation has practical consequences. People stop pooling resources. They stop coordinating responses to shared problems. They stop trusting local institutions to act fairly. Each household becomes a unit of survival rather than part of a broader social fabric.

The effects compound quietly. As trust declines, people rely more heavily on formal systems and less on informal ones. Problems that were once handled within families or communities are outsourced to institutions. That shift increases dependence and reduces resilience, even before dependence becomes explicit.

It also redirects attention. When people are encouraged to view one another as threats, structural forces fade into the background. Rising costs, declining institutional performance, and policy failures become secondary to cultural conflict. The fight feels personal even when the causes are impersonal.

This pattern is not unique to any one era or country. Societies under strain often fracture along identity lines when stress increases. What is distinctive in the modern version is the speed at which division spreads and the extent to which it invades private life. Technology did not create division, but it amplified it and monetized it.

The result is a population that is stressed and increasingly alone. People adapt by narrowing their circles, avoiding risk, and lowering expectations of mutual aid. Hardship is no longer experienced as a shared challenge, but as a private burden.

Division does not yet convince people that nothing can improve. It simply convinces them that improvement will not come from one another.

That belief prepares the ground for the next degree. Once people are isolated, demoralization no longer meets resistance. It finds fertile soil.

Demoralize

Convince people that nothing is true, fair, or fixable

Withdrawal isolates people. Demoralization convinces them that isolation is permanent.

A demoralized society is not one that is constantly outraged. Outrage still assumes that something matters enough to fight over. Demoralization is quieter. It is the belief that effort no longer produces improvement, that institutions cannot be trusted to act fairly, and that truth itself has become indistinguishable from power.

This is where many observers misunderstand the moment. They confuse demoralization with ignorance. The two are not the same. Ignorance is a vacuum. It waits to be filled. Demoralization is a shield. It deflects everything. People stop listening not because they lack information, but because they no longer believe information leads anywhere useful.

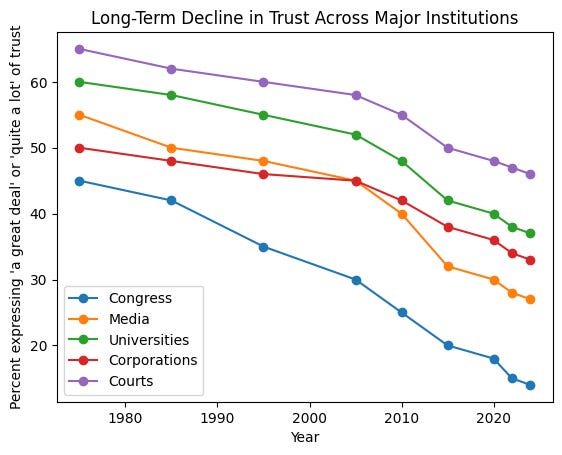

By the early 2020s, trust in nearly every major American institution had collapsed to historic lows. Surveys showed declining confidence in Congress, the media, universities, corporations, and public health authorities. Even institutions that retained higher trust, such as the courts, became increasingly viewed through partisan lenses. The result was not skepticism targeted at specific failures, but a generalized disbelief in neutrality itself.

What made this period distinct was the simultaneity of the collapse. In earlier eras, distrust focused on particular institutions or events. In the modern environment, distrust became ambient. People were encouraged to believe that the system was corrupt and illegitimate, while also being warned that questioning official narratives was dangerous. Those messages reinforced one another. When everything is suspect, discernment feels pointless.

The information environment accelerated this effect. Constant exposure to contradictory claims, each presented with confidence and urgency, overwhelmed the average person’s ability to evaluate evidence. News cycles moved faster than verification. Corrections arrived quietly, long after impressions had formed. Over time, many people concluded that truth was either unknowable or irrelevant.

This produces a specific psychological response. People disengage not because they do not care, but because caring feels futile. Participation begins to feel performative. Civic life becomes theater. Voting, debate, and public discussion lose their connection to outcomes.

Demoralization is reinforced when accountability appears absent. Highly visible failures pass without consequences. Rules seem to apply unevenly. Standards shift without explanation. For ordinary citizens, the lesson is not that the system is imperfect, which most societies can tolerate, but that fairness itself is negotiable.

At this stage, people stop demanding improvement. They focus instead on minimizing exposure to harm. They retreat into private life. They manage risk rather than pursue reform. This is not apathy. It is adaptation.

Historically, demoralization has preceded major political realignments. In late Weimar Germany, many citizens withdrew from civic engagement before the collapse became obvious. In the final decades of the Soviet system, few believed official narratives, but fewer still believed meaningful reform was possible. In both cases, demoralization hollowed out resistance before power consolidated.

The American version does not follow the same script, but the mechanism is familiar. When people believe that truth is always partisan, that institutions are always self-serving, and that outcomes are predetermined, they stop investing effort. They stop believing that persuasion or participation matters.

This is the crucial turning point. A society can survive instability and even division if people still believe improvement is possible. Once that belief collapses, dependence begins to look less like surrender and more like common sense.

Dependence does not grow out of hope. It grows out of demoralization, when relief feels more realistic than reform.

Depend

Trade autonomy for predictability

Dependence does not arrive as a doctrine. It arrives as a bargain.

Once people no longer believe that effort reliably leads to improvement, the question they ask changes. It is no longer “What is right?” or even “What is fair?” It becomes “What is safe?” Under those conditions, autonomy loses its moral glow. Predictability becomes the primary good.

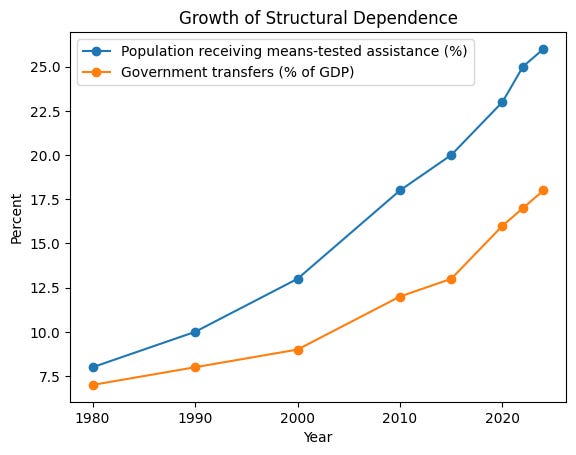

This is the point at which many analyses go astray. They assume people embrace dependence because they have adopted a particular political philosophy. In reality, most people do not experience dependence as ideological at all. They experience it as a rational response to uncertainty. When the downside risks of independence become severe, independence stops feeling like freedom and starts feeling like recklessness.

What changes most at this stage is not belief, but structure. Access becomes conditional. Participation increasingly requires approval. The ability to function in everyday life depends less on personal judgment and more on compliance with administrative systems.

Housing, healthcare, and education illustrate this shift clearly, not because they are expensive, but because they are permission based. Renting or buying property increasingly requires navigating complex regulatory and financial gatekeeping. Healthcare access depends on network inclusion, insurance status, and institutional compliance. Education depends on accreditation, credentialing, and adherence to evolving norms. In each case, the individual does not simply pay a price. He must remain eligible.

Eligibility is where dependence takes root.

As systems grow more complex, opting out becomes unrealistic. Individuals lose the ability to act independently even when they want to. Decisions that were once personal become mediated by forms, approvals, and compliance requirements. The language of rights quietly gives way to the language of access.

This dependence is reinforced socially. Independence is reframed as irresponsibility. Noncompliance is framed as recklessness or selfishness. People learn that aligning with approved norms reduces friction, while deviation introduces risk. Over time, these incentives shape behavior without the need for force.

Professional life offers a clear example. As employment becomes more centralized and credential driven, workers learn that advancement depends not only on competence, but on alignment. Expressing the wrong view, questioning the wrong policy, or failing to signal the right values can quietly close doors. Many respond by adjusting outward behavior, not because they have been persuaded, but because the cost of independence feels too high.

Dependence also expands through benefits and protections that are explicitly conditional. Assistance is tied to compliance. Stability is offered in exchange for predictability of behavior. These arrangements are often defended as compassionate, and in many cases they are. But compassion that conditions survival on alignment reshapes incentives in ways that are difficult to reverse.

The key transformation here is psychological. People stop seeing autonomy as something to be defended. They begin to see it as a liability. Risk avoidance becomes the governing principle. Security, even constrained security, feels humane compared to exposure.

This does not mean people believe they are unfree. Elections still exist. Choices still appear. But those choices are increasingly bounded by fear of disruption. People learn to manage systems rather than challenge them. They bargain rather than resist.

Thomas Sowell has often pointed out that policies should be judged by the incentives they create, not the intentions behind them. Dependence thrives when incentives reward compliance and penalize deviation, even subtly. Once those incentives are in place, behavior changes regardless of stated values.

At this stage, most people are not coerced. They are cautious. They are managing risk. They are trying to protect what little stability they have left.

That caution sets the conditions for the next degree. Once dependence governs behavior, speech becomes a calculated risk. Silence is no longer withdrawal or resignation. It becomes strategy.

That is where de-platforming takes hold.

De-platform

Make silence feel like survival

At this stage, control no longer depends on persuasion. It depends on cost.

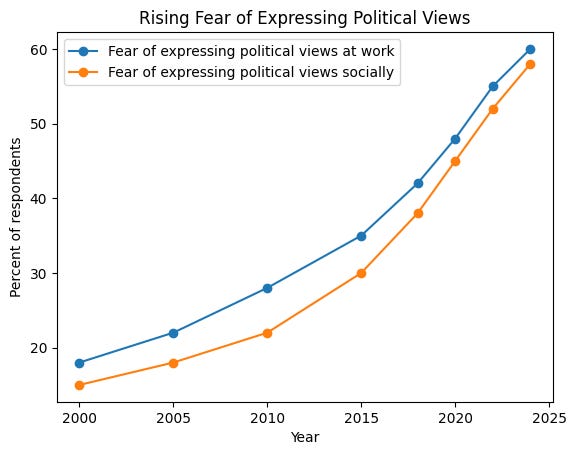

De-platforming is often misunderstood because it does not look like traditional censorship. Laws do not need to change. Speech may remain formally legal. What changes is the price of expression. People learn, quickly and accurately, which statements carry consequences and which do not.

This stage builds directly on dependence. Once individuals rely on institutions for income, professional standing, healthcare access, or social legitimacy, risk calculation becomes unavoidable. Speaking plainly is no longer a matter of conviction. It becomes a gamble.

By the early to mid 2020s, this dynamic was visible across media, corporate life, academia, and digital platforms. Journalists lost positions for deviating from accepted narratives. Professionals faced investigations, suspensions, or termination for statements made outside the workplace. Financial services began treating political and cultural views as indicators of reputational risk. None of this required a single directive. Incentives aligned on their own.

The stated justification was usually safety. Speech was labeled harmful, destabilizing, or dangerous. In some cases, these labels were applied to genuinely reckless claims. In many others, they were applied to dissent, skepticism, or inconvenient facts. The boundaries were rarely defined clearly, which made them more effective. Ambiguity encourages restraint better than explicit rules.

Digital platforms refined this process. Bans were only one tool. Algorithmic suppression, demonetization, temporary suspensions, and shadow restrictions proved more efficient. A few visible punishments signaled the risk to millions of observers. Most people adjusted behavior without ever being directly sanctioned.

The effect was not conformity of belief. It was conformity of expression.

The goal was not to change what people think. It was to break the link between what they think and what they say. Once that link is severed, public discourse loses its corrective function. Error persists because it cannot be challenged openly. Orthodoxy hardens not because it is accurate, but because it is uncontested.

Silence becomes rational at this stage. People tell themselves they are being prudent, professional, or mature. They avoid unnecessary risk. They separate private thought from public speech. Over time, that separation becomes habitual. Self-censorship no longer feels imposed. It feels responsible.

The cost is cumulative. A society that cannot speak honestly cannot diagnose its problems. A society that cannot diagnose cannot recover. De-platforming does not simply remove voices. It reshapes reality by determining which questions may be asked at all.

By the time silence becomes widespread, most people do not feel oppressed. They feel cautious. They believe they are navigating a complex environment intelligently. In truth, they are adapting to constraints that have become normalized.

That normalization clears the final path.

Destroy

Erase the possibility of recovery

The final stage is not collapse. It is normalization.

Destruction in this context does not mean physical ruin. It means the destruction of memory, standards, and comparison. It is the point at which decline no longer registers as an emergency, and alternatives no longer feel imaginable.

This stage depends on everything that came before it. Economic instability shortened time horizons. Division isolated individuals. Demoralization eroded belief in reform. Dependence made risk intolerable. De-platforming severed speech from thought. What remains is a society that cannot remember stability clearly enough to demand it.

The process is gradual. Educational standards are lowered, then redefined. Historical narratives are simplified, then moralized. Institutional competence declines, then competence itself is treated as suspect. Excellence becomes controversial. Loyalty and conformity become safer than results.

Younger generations are especially affected. Those who grow up entirely within this environment lack reference points. They are taught that current conditions are normal, that earlier periods were either oppressive or illusory, and that dissatisfaction itself signals moral failure. Without memory, comparison becomes impossible.

Institutions reinforce this condition by punishing correction. Admitting failure threatens legitimacy. Reform requires acknowledging that something once worked better. That acknowledgment becomes dangerous. Over time, systems lose the ability to self-correct because correction itself is treated as subversion.

The result is a peculiar calm. When expectations are low enough, nothing disappoints. Decline becomes background noise. People adjust aspirations downward and call it realism. Survival replaces ambition. Maintenance replaces progress.

Historically, societies that reach this stage rarely reverse course without external shock. Internal recovery requires memory, coordination, and courage. All three have already been eroded.

This is why the final degree matters most. The earlier stages weaken a society. This one makes that weakness permanent.

When Desperation Feels Normal

The six degrees of desperation do not require a conspiracy. They require incentives, exhaustion, and time. Each stage deepens the next. None demands universal belief. Most people only need to adjust behavior slightly to survive.

The danger is not that people stop caring. It is that they stop expecting better. When desperation becomes normal, relief begins to feel like freedom. When silence feels safe, truth becomes rare. When decline is treated as progress, recovery disappears from imagination.

This is not how societies suddenly fall apart. It is how they settle into something smaller than they were.

A society can survive hardship, conflict, and even failure. What it struggles to survive is forgetting that it could choose differently.

That is what makes desperation the most dangerous condition of all.

Help Keep This Work Independent

Desperation does not announce itself. It normalizes. Then it is inherited.

If this essay helped you name what you have been feeling, the next step is simple. Support the work that stays honest while everything else adjusts to incentives.

Become a Paid Subscriber

Paid subscribers fund long-form, data-driven analysis that is not written to please advertisers, institutions, or algorithms. https://mrchr.is/help

Make a One-Time Gift

If you prefer not to subscribe, a one-time contribution still helps cover research and writing time. https://mrchr.is/give

Join The Resistance Core

This is for people who believe this work is worth more than $8 a month and want to make a bigger statement. The page defaults to $1,200 a year, but you can set it to $500, $1,000, $2,000, or any amount that makes sense for you.

Think of it as a once-a-year vote that says, “This needs to exist.”

If You Cannot Give

Share this essay with someone who still values clarity over comfort. That matters more than likes.

Sign Up for the Boost Page — Free

A free way to strengthen distribution without relying on platforms that reward distortion. https://mrchr.is/boost-form

Thank you for reading this, and thank you to those who have already supported me. I’ve never taken it for granted.

I believe in this work.

I believe in where it’s going.

And with your help, I’ll keep pushing it forward.

This is brilliant! It may seem to be one of your less controversial pieces, but if readers allow it to soak in, they will see how very serious it is. I see exactly what you're talking about in my work as a teacher. The regular public schools where I used to teach are so filled with despair that it hits you as you walk in the door, or just before. I texted my mother on Friday as I waited for my assignment at a charter school where I go frequently, "The absence of despair is shocking." There are people who are trying to teach the young about high standards, Western civilization, and the power of education and autonomy. They... maybe I can say we now!... are fighting against the incredible odds you describe here: inertia, desperation, lack of hope, dependence. Watching the kids talk about the impending lack of food stamps was quite disturbing. The idea that the government should provide the food for black families is so deeply entrenched. But what I saw was responsible adults talking to the kids about how they needed to get an education so they could get a good job and provide for their own families. Every day we try. Your straight talk and insightful analysis helps me make sense of the world I live in and continue to find meaning in every day. Thank you.

A great and very thoughtful analysis, Mr. Arnell! I have followed you for awhile now, but this post has compelled me to become a supporter.

“As systems grow more complex, opting out becomes unrealistic.” Yes – but it becomes the only viable choice! And this is one more reason why in our future society, we do not want complexity. It should be noted here that complexity goes hand-in-hand with centralization, and centralization goes hand-in-hand with consolidation (and usurpation!) of power – this is why we need to decentralize in order to survive as a civilization.