The Silence of the Jabs

How Sanitation Saved Us, and the Needle Stole the Credit

The Needle Beholds the Lie

We are told a story that has become so ingrained that it passes without question. The story goes like this: once upon a time, the world was ravaged by deadly diseases, and then modern medicine stepped in with vaccines that saved humanity. It is a story repeated in classrooms, government press conferences, and media sound bites. The problem is that when you look at the actual data, the story does not hold up. As Dissolving Illusions carefully documents, mortality from the great infectious diseases had already collapsed before vaccines were widely introduced. What changed was not medicine, but sanitation.

The crowded, filthy cities of the 1800s were breeding grounds for disease. Children worked in coal mines and textile mills, families lived in single-room tenements without plumbing, and sewage ran through the streets. Water supplies were routinely contaminated with human waste. In that world, diseases such as cholera, tuberculosis, and smallpox cut people down in staggering numbers. But the deaths were not simply the product of invisible microbes. They were the result of human beings forced to live in conditions that guaranteed sickness.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the picture had already begun to change. Cities built sewer systems, water filtration systems spread, garbage collection became routine, and housing slowly improved. These public health measures, boring, unglamorous, and entirely separate from vaccines, produced the most dramatic collapse in disease mortality ever recorded. Smallpox deaths in England and Wales plummeted by the early 1900s, long before compulsory vaccination laws reached their peak. Tuberculosis, scarlet fever, whooping cough, and measles all followed the same path. The “miracle” was not a syringe, but a sewer pipe.

The World Before the Needle

To understand why vaccines could so easily claim credit they never earned, you have to picture the world that came before them. The nineteenth century was not an age of medical ignorance so much as it was an age of appalling living conditions. In city after city, disease was less the work of mysterious microbes than of visible filth and invisible neglect.

In 1840s London, cesspools overflowed into the Thames, which also served as the primary source of drinking water for millions. Cholera flourished, with outbreaks killing tens of thousands in a matter of weeks. In New York City, the Five Points slum packed more than 30,000 people into a few square blocks, lacking reliable sewage and clean water. Typhoid, dysentery, and smallpox raged in environments like that, because they had every condition they required: contaminated water, overcrowding, malnutrition, and constant exposure.

Childhood mortality statistics from this era are sobering. In the United States during the mid-1800s, nearly one in five children died before reaching the age of five. In some industrial towns in England, the rate was even higher. Dissolving Illusions cites 1849 mortality tables showing cholera claiming more than 50,000 lives in England and Wales in a single summer, with the vast majority in poor, urban areas. Tuberculosis was responsible for 25 percent of all deaths in London in the mid-1800s. Smallpox, scarlet fever, diphtheria, and whooping cough completed the cycle of misery.

Yet the connection to environment was hiding in plain sight. When cities invested in sanitation, the death toll shifted almost overnight. London’s Great Sewer Project, under Joseph Bazalgette, completed in the 1860s, dramatically reduced cholera deaths within a decade. When New York installed public water works and mandated garbage collection in the late 1800s, typhoid mortality plummeted. When milk supplies were pasteurized in the early twentieth century, infant mortality rates dropped so sharply that public health officials hailed it a revolution in child survival.

By the early 1900s, these reforms had transformed life expectancy. In 1900, the average life expectancy in the United States was about 47 years. By 1950, it had climbed to 68 years, a change attributable primarily to clean water, improved nutrition, and safer living conditions, rather than vaccines. As Dissolving Illusions makes clear with page after page of mortality charts, diseases like measles, whooping cough, and scarlet fever were already in steep decline decades before a vaccine ever entered the picture.

This is the forgotten foundation of modern health. Without this context, it is easy to imagine that syringes worked miracles. But the evidence tells a different story. The most significant public health advances of the last two centuries did not come from needles. They came from sewer pipes, clean water, better diets, and safer homes. Vaccines entered a world where the hard work had already been done.

The Data vs. The Myth

The mortality records of the last two centuries tell a story that is nearly the reverse of the one we are taught. Death from infectious disease was already collapsing before vaccines were in widespread use. The vaccine story was grafted on afterward, transforming a decline driven by sanitation, nutrition, and safer living conditions into a myth of medical salvation.

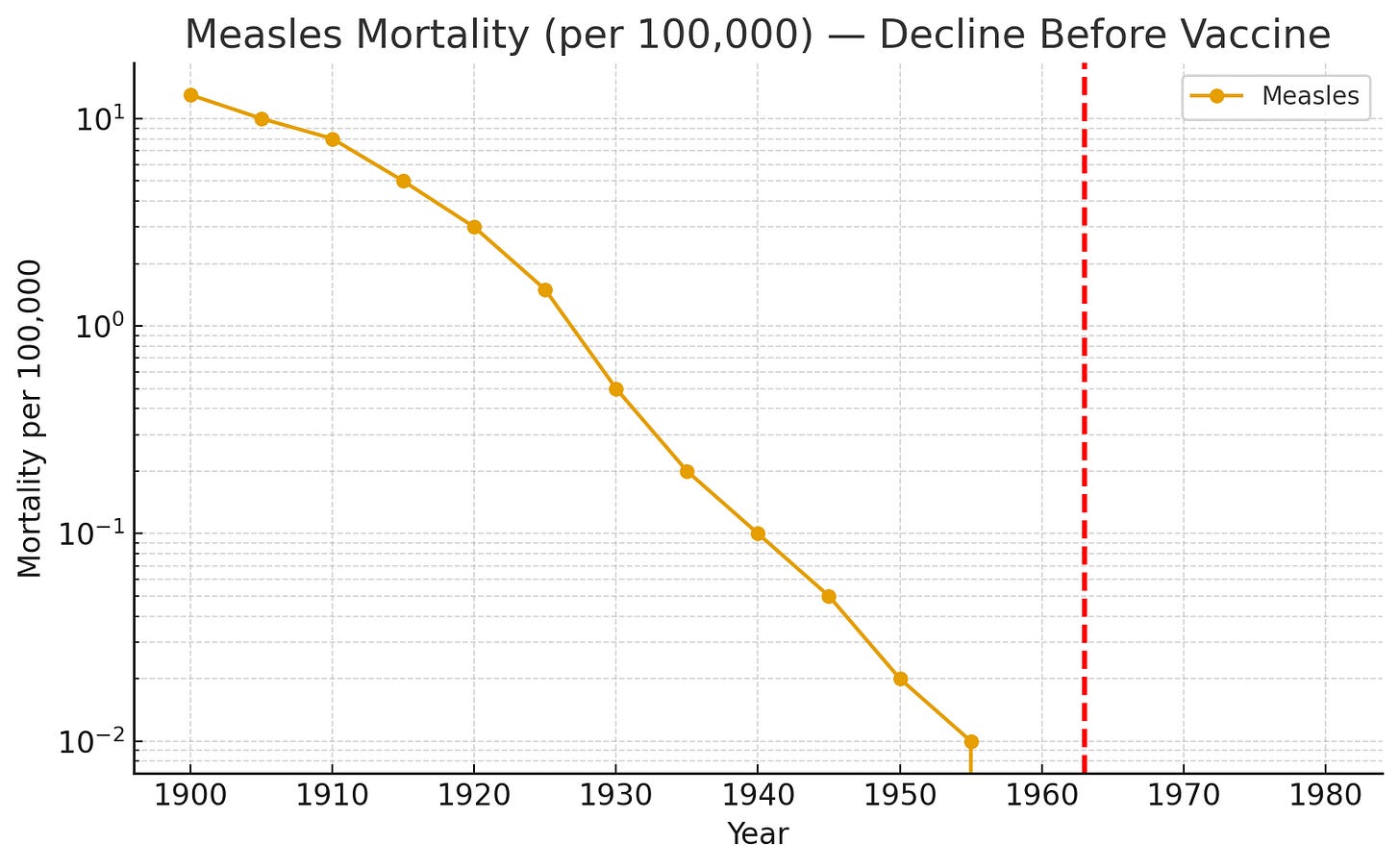

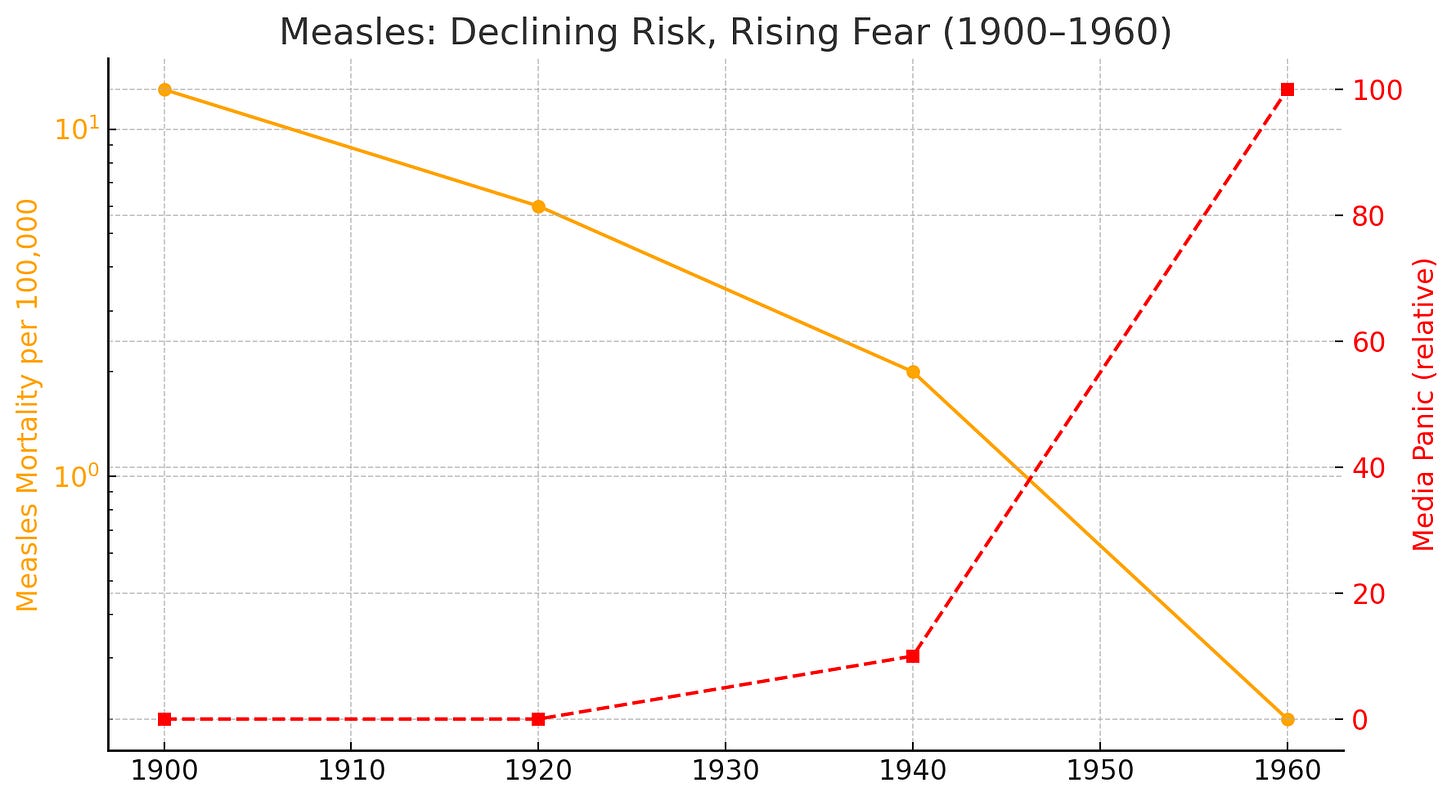

Measles

At the start of the twentieth century, measles killed about 13 of every 100,000 Americans annually. By 1955, eight years before the vaccine was introduced, the number had fallen to less than one per 100,000. In England and Wales, the decline was even more dramatic: a 95 percent reduction between 1900 and 1960. Severe cases clustered among children suffering from malnutrition and vitamin A deficiency. When vitamin A supplements were introduced in poorer regions of Africa and Asia, measles mortality plummeted by as much as 90 percent, without any change in vaccination rates. By the time the vaccine was licensed in 1963, measles had already lost its capacity to cause death in developed countries. Yet it was presented as the decisive blow, and the role of nutrition was quietly downplayed.

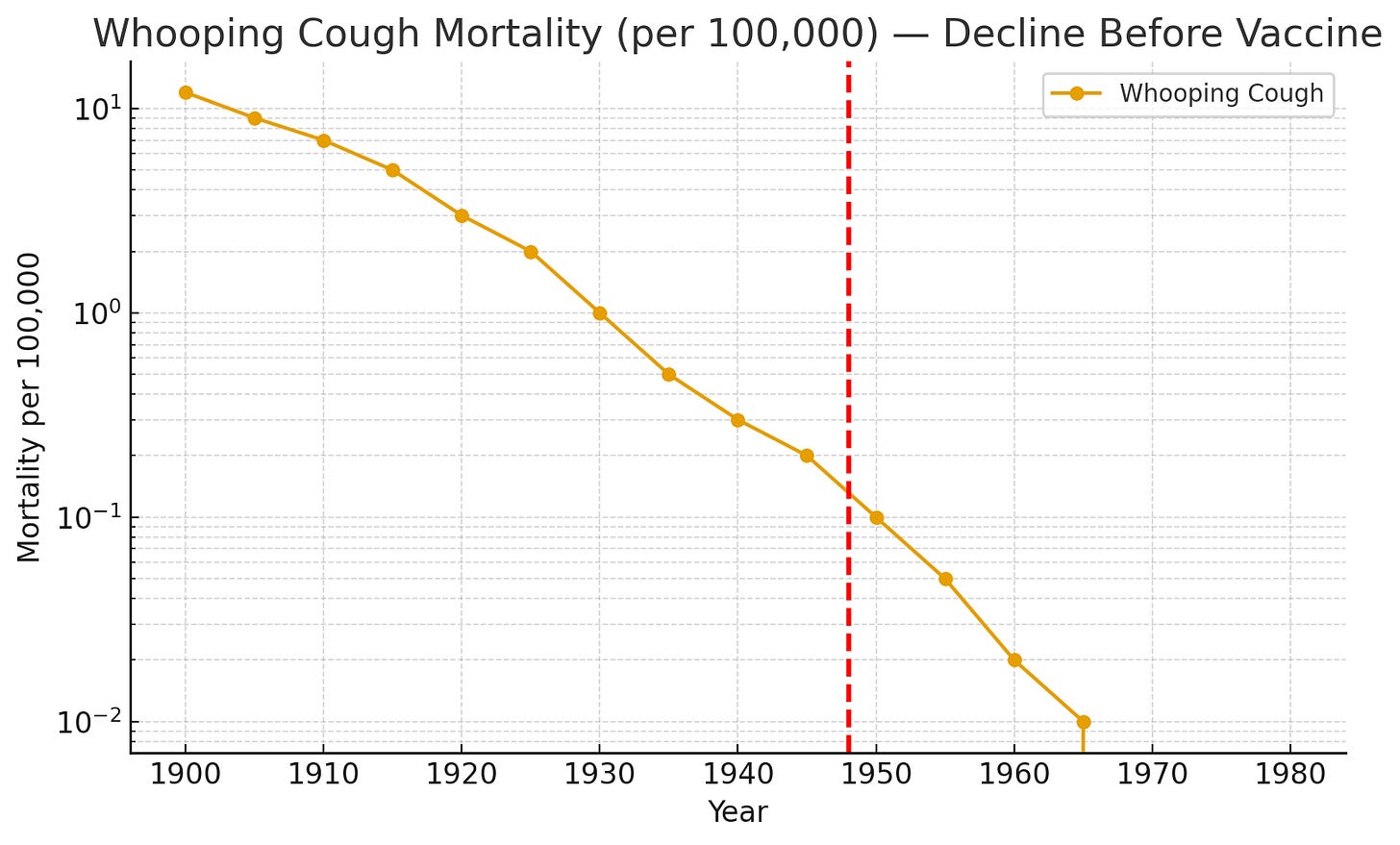

Whooping Cough

In 1915, whooping cough killed about 12,000 Americans every year. By 1945, deaths had fallen to just over 1,000, a decline of more than 90 percent before the DTP vaccine was rolled out. England showed the same trajectory. The steepest declines aligned with improvements in clean water, pasteurized milk, and wartime nutrition programs. The vaccine was introduced into a landscape where the disease was already retreating. Worse, it came with real risks: seizures, encephalopathy, and permanent neurological damage. Japan suspended the vaccine in 1975 after reports of deaths and severe injuries, and whooping cough mortality did not return to pre-vaccine levels. Sweden halted use for more than a decade for the same reasons. These episodes proved what the historical data already showed: the vaccine was not the decisive factor, but it became the only story told.

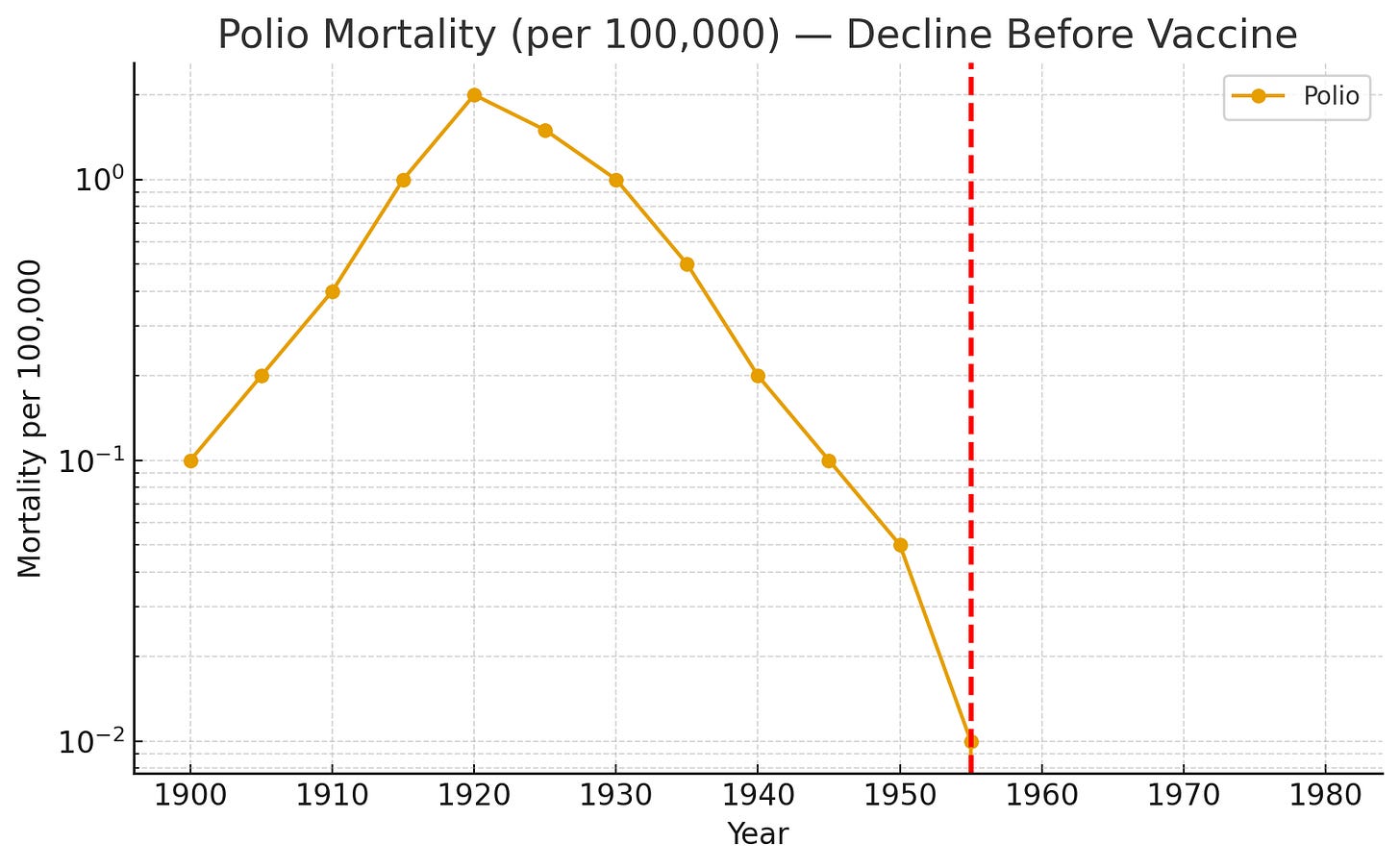

Polio

Polio’s place in public memory owes more to panic than to scale. At the height of the so-called epidemic in 1952, the United States reported 21,000 cases of paralytic polio in a population of 160 million, frightening for parents, but still a risk of about 0.013 percent. The terror came from the imagery of children in iron lungs, not from the odds. The story becomes even murkier when you look at the definitions. In 1955, the year the Salk vaccine was released, the diagnostic criteria for polio were changed. Paralysis lasting less than 60 days, once counted as polio, was excluded. Many cases were reclassified as viral meningitis or “acute flaccid paralysis.” With one bureaucratic adjustment, reported cases dropped overnight. Meanwhile, children had been drenched in DDT throughout the 1940s and 1950s, a pesticide later shown to cause neurological damage resembling polio. The decline attributed to the vaccine was just as much a product of shifting definitions and environmental changes.

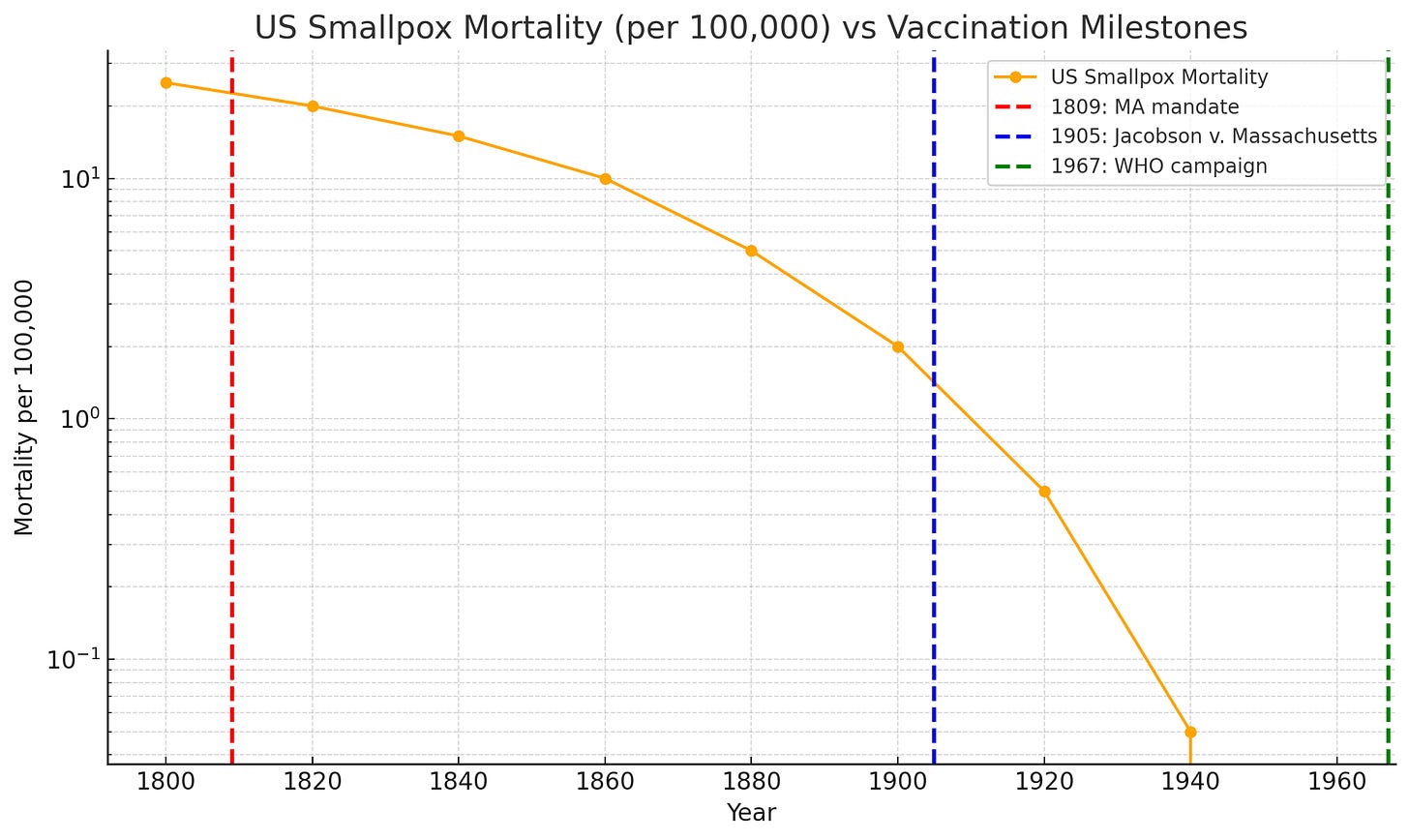

Smallpox

Smallpox is often regarded as the ultimate triumph of vaccination, yet numerous contradictions mark its history. In nineteenth-century England, epidemics struck hardest in the towns with the highest vaccination rates. While mortality rates plummeted across Europe by the early 1900s, this decline was largely driven by improvements in sanitation and quarantine measures. Yet, it was compulsory vaccination that received the credit and the force of law. In Leicester, which rejected mandates and instead relied on sanitation, isolation, and quarantine, smallpox mortality was consistently lower than in highly vaccinated cities. Vaccine production itself was notoriously unsafe, spreading syphilis, tuberculosis, and tetanus through contaminated batches. When the World Health Organization declared smallpox eradicated in 1980, it admitted that containment strategies, isolating cases, tracing contacts, and quarantining, had been decisive. Yet the official narrative allows only one conclusion: the needle saved the world.

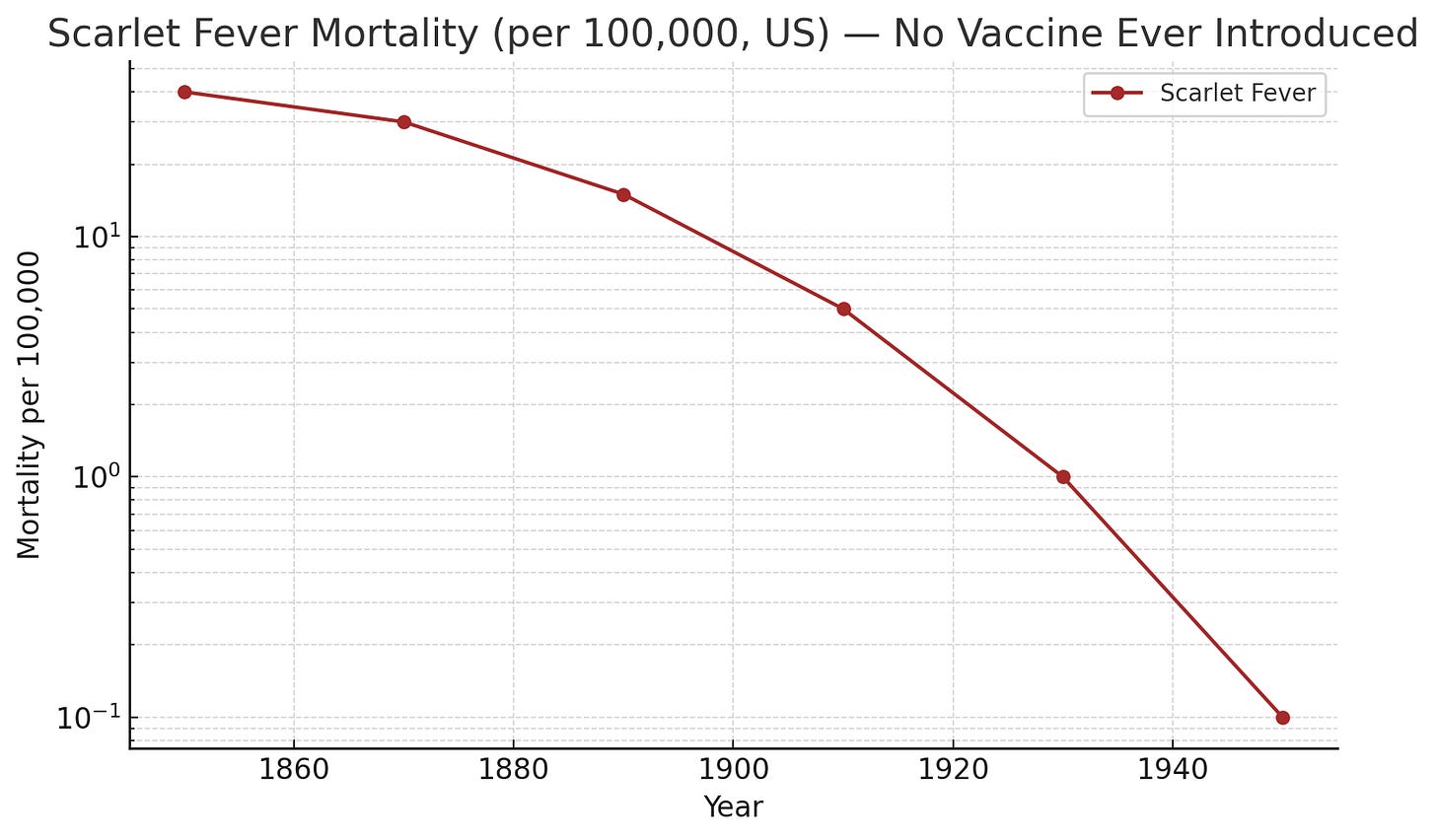

Scarlet Fever

The most devastating example of the vaccine narrative is scarlet fever. Once one of the leading causes of childhood death in the nineteenth century, it declined by more than 99 percent between 1860 and 1960, and no vaccine was ever developed. Improvements in water quality, nutrition, and housing led to its disappearance. Its disappearance is rarely discussed in the same breath as smallpox or polio because it undermines the premise that vaccines were the singular turning point. Scarlet fever demonstrates that diseases can disappear without the need for vaccination. That fact alone should have rewritten the story of public health. Instead, it was silenced.

The Pattern

Put side by side, the data tell a story that is consistent and devastating to the myth. By 1900, infectious disease mortality in the United States accounted for nearly half of all deaths in the country. By 1950, that share had fallen to less than 10 percent, primarily due to improvements in sanitation, access to clean water, nutrition, and safer living conditions. Life expectancy rose from 47 years in 1900 to 68 years by 1950. The overwhelming majority of that gain came from reduced childhood mortality, not miracle injections.

The myth persists because the silence persists. Textbooks quietly shifted the timeline, teaching generations that vaccines “eradicated” diseases that had already collapsed. Public health officials elevated the syringe because it was enforceable and visible. Sewer pipes do not inspire loyalty to the state, but needles can. The triumph was environmental. The applause went to the vaccine.

Fear as Medicine

If sanitation and nutrition were the fundamental drivers of health, then why did vaccines come to be seen as the decisive factor? The answer lies not in data but in fear. From the very beginning, officials discovered that fear could do what evidence could not: secure obedience.

Smallpox set the template. Even after mortality had plummeted, governments enforced compulsory vaccination with fines, prosecutions, and prison sentences. More than 200,000 families in Britain were dragged into court during the late nineteenth century for resisting. The medical evidence was mixed, but the political lesson was clear: fear could be harnessed, and law could be used to enforce it. Leicester, which achieved lower mortality through sanitation and isolation, was treated not as proof but as a nuisance to the official narrative.

The same playbook surfaced with polio. In raw numbers, paralysis was rare, but the images of children in iron lungs burned into public memory. Newsreels and photographs bypassed statistics and seared the fear into parents’ minds. The bureaucratic redefinition of polio in 1955, which instantly lowered case counts, was never explained to the public. The vaccine was credited with victory, while fear ensured no one asked too many questions.

By the 1960s, measles was a mild childhood illness for the vast majority, but public health campaigns recast it as a menace that required urgent vaccination. A 1969 Time magazine cover labeled it “The Measles Menace,” even though mortality had already dropped by over 98 percent. The disease was fading on its own, but the rhetoric kept the fear alive.

Even the disappearance of scarlet fever, without any vaccine, was buried in silence. A disease that killed tens of thousands of children in the nineteenth century was gone by the mid-twentieth century. Rather than publicize the fact that sanitation and nutrition could banish a disease completely, officials chose to say nothing. Silence was the ally of fear.

By the late twentieth century, vaccination had become more than a medical measure. It was a civic ritual, reinforced by images, laws, and rhetoric. Dr. Suzanne Humphries has described this transformation as the birth of a kind of “vaccine religion,” and Roman Bystrianyk’s ongoing essays show how propaganda replaced analysis. Numbers did not persuade the public. They were herded by images, by mandates, and by fear.

The Power Grab

Fear softened resistance, but it was the state that hardened compliance. Once officials realized that disease panic could be harnessed for political gain, vaccination campaigns shifted from being primarily about health to being more about establishing authority.

The smallpox mandates of the nineteenth century were the proving ground. Britain’s Compulsory Vaccination Acts made inoculation a legal requirement. Parents who refused were fined repeatedly, sometimes dragged into court dozens of times, and in some cases, mothers were jailed. By the end of the century, more than 200,000 prosecutions had been carried out against families who resisted the authorities. Whether or not the policy worked medically, it succeeded politically. It established the principle that the state, not the parent, had the final say over the child.

The same logic spread across Europe. Germany’s 1874 law tied vaccination to school attendance. Italy restricted public services to those who complied. France pressed ahead with mandates despite outbreaks in vaccinated populations. The success of these policies was not measured in reduced mortality, but in increased obedience.

The United States followed suit through the schools. In 1905, the Supreme Court’s Jacobson v. Massachusetts ruling upheld the government’s right to mandate vaccination under the “common good.” The penalty in that case was a $5 fine, about $150 today, but the precedent was far more significant than the punishment. It cemented the principle that the government could compel medical interventions. By the 1970s, all fifty states had school vaccine laws on the books, and exemptions became increasingly narrow with each passing decade. Education itself had become leverage.

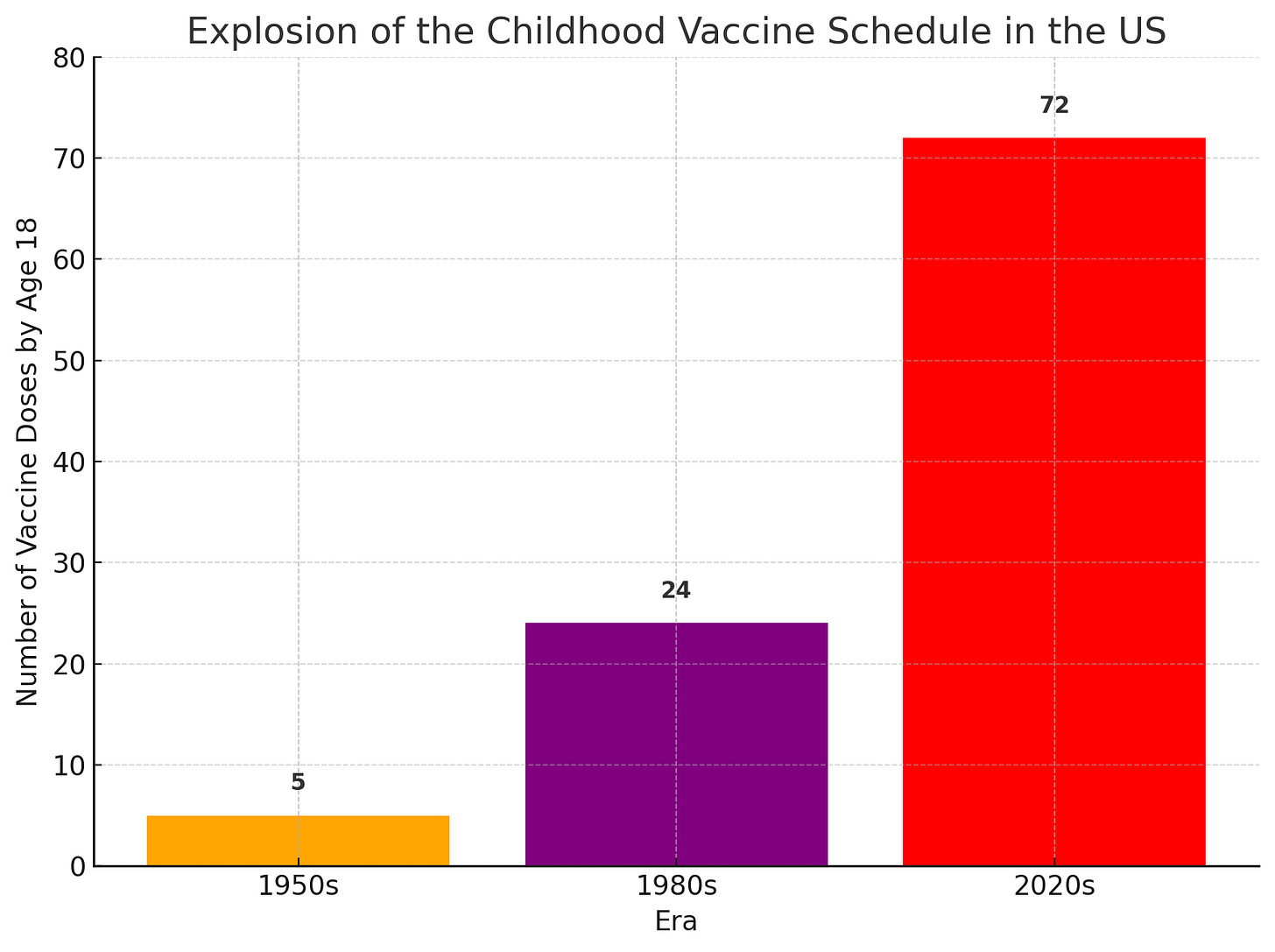

Globally, vaccination became a symbol of state capacity. It was easier to line people up for injections than to build sewer systems or secure food supplies. Organizations like the World Health Organization and UNICEF promoted mass vaccination drives in poor countries, even where clean water and sanitation, the absolute lifesavers, remained out of reach. Shots were visible, enforceable, and politically expedient in a way that sewer pipes never were.

This same model came roaring back in our own time. During the COVID-19 pandemic, governments revived the old playbook almost word for word. Vaccine passports determined access to schools, jobs, restaurants, and even grocery stores. Federal mandates tied compliance to employment. Natural immunity was ignored, dissent was punished, and the vaccine was elevated from one tool among many to the only ticket back to everyday life.

The continuity is unmistakable. From the smallpox prosecutions of nineteenth-century Britain to the COVID mandates of the twenty-first century, vaccination has been less a medical milestone than a political one. It became the state’s most direct instrument of control over the individual body. Where sanitation, nutrition, and safer housing empowered families and communities, vaccination mandates empowered the government to dictate terms. That is why the story of sewers was buried and the story of syringes was celebrated. Power, not public health, demanded it.

The Silence

The most striking fact about the history of infectious disease is not how much was accomplished through sanitation, nutrition, and safer living conditions. It is how little of it people remember. That silence was not a mistake. It was engineered.

By the middle of the twentieth century, the evidence was overwhelming. Mortality from measles, whooping cough, and tuberculosis had already collapsed. Scarlet fever disappeared entirely without a vaccine. Smallpox waned as sanitation improved and outbreaks were contained. These numbers were in public records, medical journals, and government reports. But they were slowly erased from memory. Textbooks rewrote the timeline. Generations were taught that vaccines “wiped out” diseases that had already declined. The syringe became the hero. The sewer was written out of the story.

Silence also concealed the contradictions. Leicester’s sanitation-based strategy, which outperformed mass vaccination, was ignored. Japan’s suspension of the whooping cough vaccine in the 1970s, which did not bring back high mortality, was sidelined. Scarlet fever’s vanishing act without a vaccine was treated as irrelevant. Facts that did not fit the narrative were left to rot in archives.

That same silence carried forward into the twenty-first century. From the very beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the data showed who was at risk: the elderly, the frail, and those with multiple chronic conditions. In Italy, the median age of the dead was 82. In the United States, nearly 80 percent of deaths occurred among those over 65 with comorbidities. These truths should have guided targeted protection. Instead, they were buried beneath headlines of mass graves and body bags. The fear was spread across the entire population, and silence about the actual risk profile created the pretext for sweeping controls.

When vaccines arrived, the story followed the old script. They were presented as the singular path out of crisis. Passports, mandates, and restrictions turned compliance into the price of participating in society. Natural immunity was dismissed. Adverse reactions were suppressed. Countries that took lighter approaches, like Sweden, were treated as reckless outliers, just as Leicester had been more than a century earlier.

The continuity is exact. Smallpox mandates in the 1800s, the polio panic of the 1950s, and the COVID debacle all share the same anatomy: a foundation of fear, a silence about the true drivers of health, and the conversion of medicine into a tool of control.

Thomas Sowell once wrote, “Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored.” They cease to exist only when they are buried beneath a narrative powerful enough to make people forget. The mortality charts of the last two centuries tell one story. Governments, media, and institutions tell another. The tragedy is not just that sanitation saved us while vaccines stole the credit. The tragedy is that by silencing that history, we left ourselves open to the same deception again, and COVID proved how easily the old playbook could still be run.

This Is Your Wake-Up Call

This isn’t a hobby; it’s how I support my family and build something bigger - an organization that exposes lies, breaks propaganda, and restores truth. Real change doesn’t happen on fumes. It has to be funded.

I work this mission seven days a week. Researching, writing, charting, connecting dots. I can’t do it as a one-man show. I need paid subscribers. I need donations.

If you read my work, you know I’m not playing. If you want real change, step up before it’s too late.

Become a Paid Subscriber: https://mrchr.is/help

Join The Resistance Core (Founding Member): https://mrchr.is/resist

Buy Me a Coffee: https://mrchr.is/give

Give a Gift Subscription: https://mrchrisarnell.com/gift

Every click, every share, every dollar matters. They don’t just want to control the debate; they also want to influence it. They want to erase reality itself.

What about Rabies?

Anything similar for bicycle helmets? It’s more about the money, control is just a nice to have.