When the Left Wins, You Lose

What Happens When Democrats Reject Majority Rule

Democracy was supposed to mean that the majority ruled. In twenty‑first‑century America it means the Left rules, and the majority obeys.

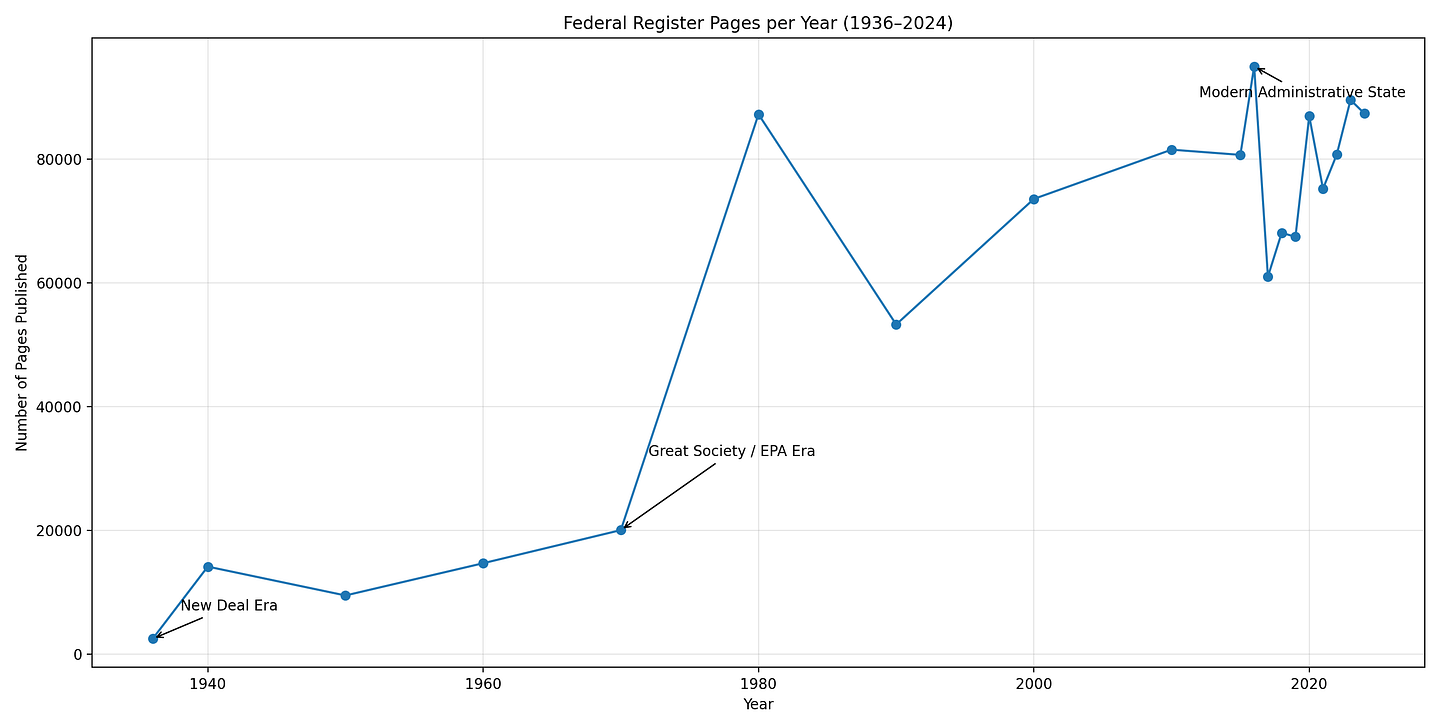

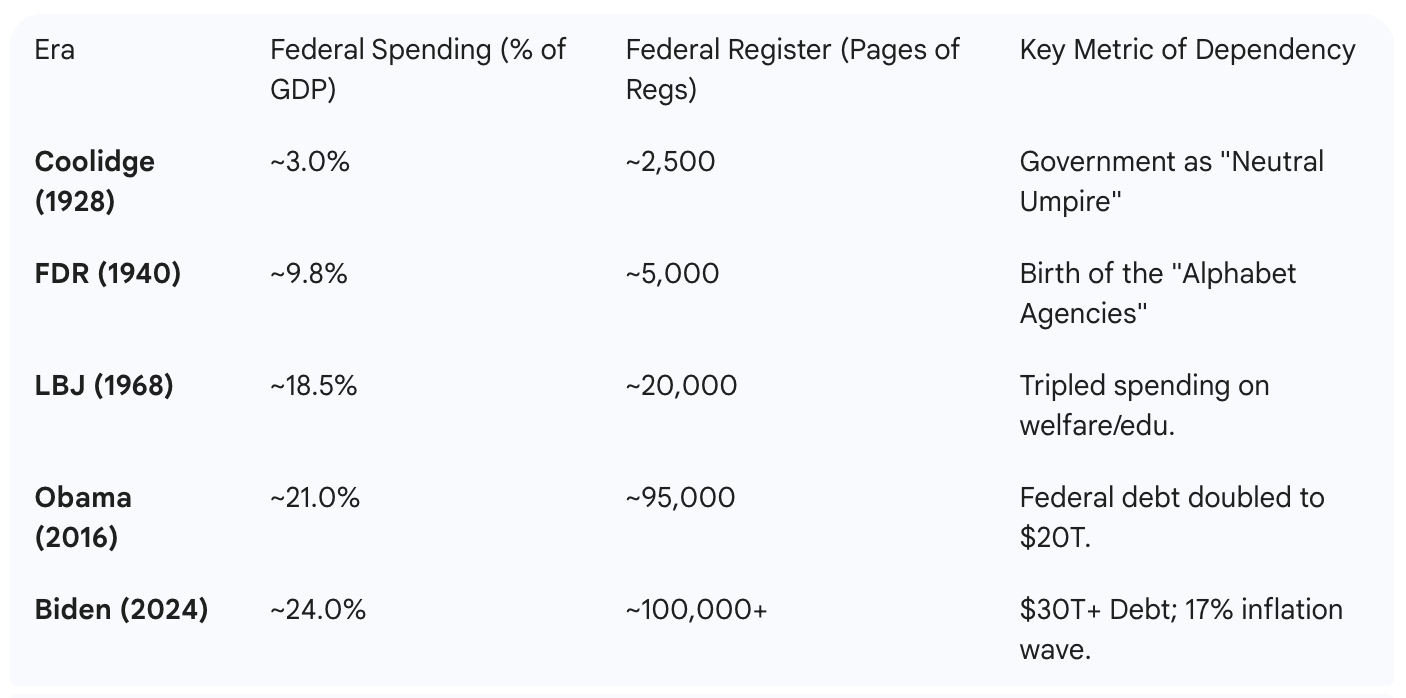

Transformation did not happen overnight. Its roots go back nearly a century, when Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal turned Washington from a neutral umpire into a player with its own stake in the game. Before 1933, the federal government mostly built roads, maintained the military, and managed the currency. Roosevelt’s answer to the Great Depression did more than expand those duties; it redefined the purpose of government itself. In the name of saving capitalism, he created a permanent political class whose survival no longer depended on private enterprise or the outcome of elections. By the time he was finished, the referee of American life had put on a uniform and joined one of the teams.

Part of that change came through taxes. The federal income tax had existed since 1913, when the Sixteenth Amendment authorized it, but only a small fraction of Americans ever paid it. Rates were modest, usually between one and six percent, and the federal government lived within a narrow budget. World War I briefly raised rates to pay for military costs, but through most of the 1920s, the government cut taxes again, and the economy boomed. When Roosevelt arrived in 1933, he saw the income tax not just as a way to raise money but as a way to lock in dependency. In the space of three years the top rate climbed from 25% to more than 60%. In 1935, he added payroll taxes through the new Social Security program, guaranteeing that the federal government would stay attached to every paycheck in the nation. The crucial step came in 1943, when Congress introduced tax withholding. From then on, Washington collected its share before workers ever saw their income, which turned citizens into clients rather than customers of their own labor.

Those changes were about more than revenue. They altered incentives. Once government funding could expand every year through automatic deductions, there was no real need for restraint. Agencies and programs matured into permanent voting blocs. By 1950, federal spending made up roughly 20 percent of national output, compared with only 3 percent in 1928. The New Deal produced a wave of new federal programs known collectively as the “alphabet agencies,” such as the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and the National Recovery Administration (NRA). These agencies managed farming, employment, wages, and prices, and by the late 1930s they had multiplied into a permanent web of government programs that reached into nearly every corner of the economy. Each depended on the taxes Roosevelt institutionalized, which meant every dollar taken in justified a new dollar spent. The income tax had quietly become the fuel of the administrative state.

Before long, the bureaucracy itself began to shape public opinion. When federal programs employ your neighbors, fund your town projects, and regulate your business, it becomes difficult to imagine life without them. Politicians in both parties learned that cutting programs could look cruel, even when those programs failed to work. Democrats leaned into that dependency. They spoke of government as the instrument of national compassion while using it to reward loyal constituencies. Republicans, wanting to appear moderate, usually left the structure intact. What began as an emergency response to the Great Depression evolved into a standing political army that no election could disband.

That is why the same Democrat networks that built the New Deal still frame the vocabulary of modern politics. Federal grants became the lever of persuasion. If a city wanted funding for roads or schools, it accepted federal conditions written by unelected officials in Washington. A citizen might vote to keep government small, but his local representatives depended on money tied to New Deal‑era laws. In practice, the bureaucrats won every argument before it began.

Understanding this history clarifies how the present works. The agencies that grew under FDR never disappeared; they simply changed subjects. Where they once planned farm output, they now plan energy production, curriculum standards, and medical compliance. The pattern is the same. Voters are told that expert regulation equals fairness, while any attempt to reverse it amounts to extremism. When the Democrat Party commands the bureaucracy, it calls decisive action “progress.” When Republicans try to govern through the same offices, it becomes “authoritarianism.”

The enduring power of the Left comes not only from elections but from the institutions that remain after elections end. Taxes supplied the money, bureaucracy supplied the permanence, and moral language supplied the cover story. Until the country finds a way to make those institutions answer directly to the voters again, the majority will keep obeying whoever controls them.

When Niceness Became Tyranny

By the middle of the 1960s, the Democrat Party had discovered something that Franklin Roosevelt only hinted at: compassion could be weaponized. The Great Society of Lyndon Johnson taught a generation of politicians that if you wrap any policy in the language of kindness, you can expand government forever. A rule that would have been shouted down as socialism in the 1930s could now be sold as caring for the poor.

Between 1964 and 1968, federal spending on welfare and education tripled. The poverty rate barely moved, but Washington’s control of local economies increased. By 1970, one in every five American dollars passed through a federal office before reaching a citizen. Once again, the stated goal was fairness; the real outcome was dependency. Federal influence no longer stopped at job sites and farms; it defined what counted as virtue.

In Sowell’s terms, the new moral culture separated people who talked compassion from those who did results. Bureaucrats became saints of intention. If a policy failed, it simply needed more budget, more staff, or more regulation. Those who pointed out the failure were scolded as heartless. Public debate shifted from “does it work?” to “are you a good person for supporting it?” That change locked a whole country into moral blackmail.

The lesson reached far beyond economics. The same pattern soon shaped race relations, gender policy, and education. Any outcome gap, no matter its cause, turned into proof of injustice. To question that logic was social suicide. From that point forward, even Republican leaders learned to speak the language of Democrat morality, hoping voters would forgive them for existing. The Great Society had not just enlarged the state; it had rewritten the definition of decency.

When moral speech becomes law, politics stops being negotiation and becomes church doctrine. The new priests were media editorial boards and tenured experts. Every Republican administration since Johnson has entered office under moral probation. Every Democrat administration receives headlines promising redemption. By the time Jimmy Carter left and Ronald Reagan entered the White House in 1981, the bureaucracy already spoke a dialect no outsider could change.

What happened next under Reagan should have been the breaking point. He revived growth, reduced inflation, and faced down the Soviet Union, yet the same cultural machinery that sanctified Johnson branded him dangerous. The press treated his optimism as propaganda. When John Hinckley Jr. shot Reagan in 1981, the first shooting of a sitting president in seventy‑seven years, the national mood treated it as a curiosity, not a symbol of escalating hatred.

Compare that with Donald Trump’s case. When he was nearly assassinated at a Pennsylvania rally in July 2024, the same culture reacted in a whisper. Commentators described it as “tragic” but immediately pivoted to warnings about “right‑wing rhetoric.” Imagine the coverage if a bullet had grazed Obama. Federal agencies held press conferences for months when threats were made against Barack Obama, yet Trump’s actual wounding was covered as a footnote. That contrast exposes the depth of moral partisanship Roosevelt and Johnson left behind.

The more the Left moralizes power, the more violence becomes a form of absolution. In 2024, two assassination attempts against Trump were treated not as national crises but as interruptions in the news propaganda cycle. The first was the sniper fire in Butler, Pennsylvania, which tore through his ear and killed a supporter standing nearby. The second, in Florida later that year, was stopped only because agents intercepted weapons and written plans. Both proved that hatred of the opposition has been normalized to the point where deterrence depends more on luck than on shared conscience.

People who still believe that government can remain morally neutral need to look at that pattern. Since 1865, four Republican presidents have been assassinated or wounded by gunfire: Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley, and Reagan, and now Trump joins that list as a survivor. Only one Democrat president, Kennedy (coincidentally pro-military, anti-communism, for lower taxes - hmm, wonder who killed him?), has been killed. Counting confirmed attempts and plots, nearly two‑thirds of all efforts to murder American presidents have targeted Republicans. Yet the institutional narrative insists that political violence is primarily a conservative problem. Numbers tell a different story.

When politics becomes religion, fairness becomes a sin. The kindness industry that began under Johnson now justifies censorship, censorship justifies propaganda, and propaganda shields power from accountability. What used to be the language of compassion has hardened into a bureaucracy of control. Ordinary voters feel it every time they see one set of laws for elites and another for everyone else. The moral revolution promised equality and delivered hierarchy, built on guilt, fear, and credentialed authority.

Until the public stops confusing sentiment with virtue, that system will keep growing. As Sowell wrote decades ago, “When you want to help people, you tell them the truth; when you want to help yourself, you tell them what they want to hear.” For the past half‑century, the Democrat Party has built its entire identity around the second option. The cost has been measurable, debt in the trillions, dependency in the millions, and a culture so polite about lies that it can no longer see them.

How the Right Won Elections and Lost Control

By the late 1960s, millions of Americans thought they were voting for a course correction. Urban riots had burned out whole neighborhoods. Inflation was climbing. Students were waving the flags of Cuba and North Vietnam, and the counterculture had filled television screens with contempt for the same people who paid the bills. In 1968, Richard Nixon promised a return to order, and most of the country believed him.

What few realized was that the New Deal’s bureaucratic architecture and the Great Society’s moral language were already fused. The federal government no longer had to be run by Democrats for Democrat policies to continue. Nixon could win an election by a landslide, but he would still have to govern through a professional class that largely despised him. The civil servants who wrote the rules, graded the grants, and briefed the journalists were already operating inside an ideological frame built by the Left and reinforced by the culture.

Nixon was no small‑government radical anyway. He accepted the framework he inherited. Under him, Washington created the Environmental Protection Agency, expanded affirmative action, and indexed Social Security to inflation, guaranteeing its perpetual growth. These were handed down as moral mandates, so resisting them carried social penalties even for a Republican president. When Nixon tried to impose executive discipline on that bureaucracy, cut budgets, reorganize agencies, or slow regulations, the press and Congress accused him of authoritarianism. Once Watergate broke, those same institutions used his wrongdoing to discredit everything associated with conservative reform. His resignation in 1974 became the media class’s proof that moral enlightenment had triumphed over corruption.

That single event reshaped politics for a generation. Bureaucrats learned that if they cooperated with journalists and prosecutors, they could decide who survived in Washington. The modern administrative state discovered how to outlast any elected official through scandal management. The idea that “unelected professionals” might be the real government was no longer cynical; it was a practical strategy.

Gerald Ford inherited Nixon’s seat and lasted just enough time to confirm this shift. His brief tenure, combined with Jimmy Carter’s one term, left both parties trying to act like moral wards of the media. Democrats preached virtue through regulation while Republicans imitated the tone to avoid blame. By the time Ronald Reagan entered the stage in 1980, Americans were tired of weakness and stagflation. His campaign slogan, “Let’s Make America Great Again,” was not a marketing trick; it was a whistle to a demoralized middle class that still believed it had a voice.

Reagan changed tone, not structure. He cut top tax rates from 70 percent to 50 percent in his first fiscal law and again to 28% by the end of the decade. Inflation fell from double digits to 4 percent, and unemployment declined from near 10% to 5%. The economy grew by roughly a third in eight years, the longest peace‑time expansion in history. Yet spending never truly decreased, regulations never vanished, and the bureaucracy learned a new skill: how to look cooperative while waiting out presidents.

Within Washington’s offices, Democrat holdovers remained the permanent staff. They drafted environmental standards, education guidelines, and social‑policy memos that Reagan never personally saw. Every reform required persuading an agency that had no interest in cutting itself down. Political appointees came and went; senior civil servants stayed for thirty years. It was career job security disguised as moral duty.

Reagan was the first conservative leader since Coolidge to match charisma with real results. But the cultural institutions, the networks, universities, and editorial boards, acted as the opposition party he hadn’t defeated at the polls. When he restored American confidence and called the Soviet Union an evil empire, journalists labeled it “simplistic.” When he won the Cold War without firing a shot, they credited Gorbachev’s charm instead of Reagan’s strategy. The public saw prosperity and strength; the bureaucracy saw danger.

Then came the event that proved how deep that resentment ran. On March 30, 1981, John Hinckley Jr. fired six shots outside the Washington Hilton. A bullet tore through Reagan’s lung, missing his heart by an inch. For days, the federal capital pretended to pray for him, but the tone of elite commentary told another story, a calm satisfaction that the “cowboy conservative” might finally be a one‑term relic. Reagan survived, recovered, and walked back into the Oval Office within two weeks. Washington could not quite forgive him for that.

What followed was clear: a conservative could inspire voters, lower taxes, and even defeat communism, but he could not dislodge the permanent culture of Washington. Every regulation he froze, the next Democrat president would revive. Every judicial appointment he made faced open sabotage in the lower courts. When Reagan left office in 1989 with record approval, the bureaucracy simply rolled back to its usual direction. The machine outlasted another reformer.

That is the essence of the conservative mirage. The Right wins elections, but the Left governs institutions. Nixon, Reagan, and later both Bush presidents discovered the same trap: you can occupy the White House, but you cannot occupy the state. Real power resides in the people who keep their jobs no matter who wins, the people who interpret your orders and file your memos. They shaped the environment that would one day turn law enforcement into a political weapon and the press into its public‑relations wing.

By the end of the 1980s, the scoreboard looked balanced, four Democrat terms, five Republican, but the field was tilted. Bureaucracy was permanent, media was ideological, academia supplied justification, and corporate money learned to flatter whichever side wrote the rules. Americans thought they were living in a fair contest of ideas. In truth, one party had built the institutions; the other merely rented them for four-year terms.

The Soviet Union had collapsed, but domestic central planning hadn’t. It just moved its office from Moscow to Washington, wrapped in red ink instead of red banners. The conservative mirage would continue through Clinton, Bush, and Obama, each chapter proving the same bitter rule: you can’t fix a system that no longer admits it’s broken.

How Clinton & Obama Perfected Permanent Power

When the Cold War ended, Washington entered the 1990s convinced it had won history itself. The Soviet Union was gone, the economy was humming, and the federal machine built under Roosevelt and Johnson looked immortal. Bill Clinton inherited that system and did what every clever manager of empires eventually does: he promised to reform it. “Reinventing government” became the slogan, a phrase that suggested efficiency while concealing expansion.

Clinton argued that by outsourcing work to private contractors he could shrink the state. What actually happened was subtler and more durable. The alphabet agencies that once coordinated dams and factories now coordinated consultancies and nonprofits. Tens of thousands of government functions moved off the official payroll, but the same offices wrote the contracts, set the metrics, and paid the bills. A new professional class emerged, people who lived from one federally funded project to the next, technically private yet dependent on public money.

That was the birth of the modern managerial state. It no longer needed civil‑service armies to exert control; it could rule through grant language, compliance checklists, and performance audits. The bureaucracy had learned to survive as a franchise. Its members shared a distinctive worldview: that the nation’s problems could be solved by experts quoting statistics rather than citizens exercising judgment. They called their creed pragmatism, but it was ideology in a lab coat.

The permanent class, now spanning government, academia, and corporate boards, developed habits that every later administration would struggle to break. Bureaucrats stayed while presidents rotated, and the press increasingly measured virtue by cooperation with those bureaucrats. The 1996 Telecommunications Act, which Clinton presented as modernization, consolidated media ownership so completely that half a dozen conglomerates soon defined acceptable opinion. The watchdog and the institution become one animal when they share the same feeding bowl.

Clinton governed through moral language the same way Johnson had, but with better market research. Welfare reform, global trade, and foreign intervention were all wrapped in the same tone of managerial empathy. Scandal management completed the transformation. The Monica Lewinsky hearings taught the elite class how to weaponize reputation and public boredom simultaneously. Transparency had once been a civic virtue; now it was a crisis to be managed. When survival requires constant moral theater, sincerity disappears.

Eight years later, Barack Obama entered a country that still believed the machine could correct itself if only led by someone polished enough to sound above politics. He was that person. His campaign sold calm competence to a public exhausted by the Bush‑era war and recession. Yet beneath the optimism, he expanded the Clinton template into the digital age.

What Johnson had invented in rhetoric, and Clinton had optimized through management, Obama turned into an automated moral system. His administration did not need to speak compassion; algorithms spoke it for him. Federal agencies, once known for paperwork, now produce data dashboards and behavioral‑nudge campaigns. Technology allowed rules to multiply faster than Congress could read them. Entire industries appeared whose sole task was to interpret federal guidance before it became regulation. Every new policy produced a moral vocabulary, fairness, inclusion, and sustainability, designed to prevent argument before it began.

Lobbyists and social‑media consultants merged into a single persuasion class. The Environmental Protection Agency treated carbon dioxide as pollution, the Department of Education nationalized student debt, and the Justice Department imposed “pattern or practice” oversight on local police. In each case, authority grew not by honest vote but by procedural declaration. Compassion, once a sermon, was now executable code.

By Obama’s second term, the permanent bureaucracy had become the credentialed ecosystem: agencies, media, universities, and technology firms singing the same hymn of moral inevitability. Compassion equaled progress, progress equaled compliance, and compliance equaled virtue. The language first drafted in Johnson’s Great Society half a century earlier had achieved digital immortality.

What had begun as paperwork in the New Deal and moral instruction under Johnson emerged under Obama as a self‑regulating ideology. It could govern a nation even when elections disfavored it, because it no longer relied on persuasion. Once morality is automated, disagreement becomes malfunction. That is the system the next decade would inherit, the perfect bureaucracy, invisible, well‑intentioned, and nearly untouchable.

How Global Power, Big Tech, and Media United After 2020

By the time Barack Obama left office, the new moral machinery was running by itself. The rhetoric of fairness had become software; the culture of compliance had become profit. No executive order could stop it because it no longer required permission. The state had found its ultimate disguise: invisibility.

From the outside, America still looked free and competitive. Elections happened, companies thrived, and citizens spoke without fear of knock on the door. Yet beneath the surface, a single system linked government, media, finance, and technology through shared vocabulary. Words such as equity, diversity, and sustainability spread across grant proposals, boardrooms, and newsrooms as if issued from one central printer. Moral consistency replaced debate as the test of belonging.

Obama’s parting expansion of surveillance, data coordination, and public‑private partnerships left behind an apparatus that could manage behavior more effectively than law. Agencies like Homeland Security and Health and Human Services had learned to steer opinion under the banner of safety. Tech companies mirrored those priorities because they relied on government contracts and global goodwill. It was the moment when political legitimacy fused with digital reputation. To be credible online meant agreeing with authority.

When Donald Trump entered the White House in 2017, he collided head‑on with that self‑sustaining network. His presidency proved that the real opposition was not a party but a culture of perpetual supervision. The agencies leaked, the press amplified, and the newly confident tech platforms curated outrage at industrial scale. Norms meant control, and anyone who threatened control became “norm‑breaking.”

The attempt to govern outside the digital moral framework failed for reasons larger than personality. The system could not admit error because its virtue was its license to exist. Every attack on Trump confirmed its own righteousness. By the end of his term, the alignment among bureaucracy, big media, and big tech was no longer a rumor. It was a formal coalition, and crisis would be its business model.

The 2020 pandemic arrived as a gift to that coalition. A biological threat justified every kind of bureaucratic authority, public health, financial stimulus, speech regulation, and surveillance. Emergency orders replaced legislation. Decisions written in coordination between data firms and health officials reached farther into daily life than any war measure in American history. What Johnson had once called compassion for the poor became compassion for the frightened. Fear proved even more efficient than guilt.

Lockdowns trained citizens to obey information rather than evaluate it. Independent specialists who questioned official guidance found themselves erased from social platforms and disinvited from professional societies. The system had achieved the dream of every administrative empire: voluntary compliance through moral intimidation. When vaccines arrived, dissent itself became heresy; people defended mandates as though they were acts of virtue. Public health had become theology with graphs.

The 2020 election cemented this mindset. Mail voting and emergency procedures were portrayed as moral duties. Any concern about process became an attack on democracy itself. The phrase our democracy, repeated endlessly by media and officials, began to mean not “government by the people” but “government by those who manage the people.” When Biden took office in January 2021, he inherited not a country in need of unity but a bureaucracy intoxicated by obedience.

Biden did not need to create institutions of control; they were already global. What he provided was tone and permission. Under the language of healing, the moral automation of the Obama years became the moral enforcement of the Biden era. Federal agencies that had experimented with content moderation during the pandemic now met weekly with social‑media companies. The Department of Homeland Security expanded domestic threat categories to include ideas. Central bankers promoted “equitable finance.” Regulators encouraged energy rationing as a form of empathy for the planet. Compassion had evolved into command.

Meanwhile, Washington rediscovered scarcity as a governing tool. Energy restrictions and monetary inflation, products of policy, not fate, were repackaged as sacrifices for noble causes. The message was constant: hardship equals goodness. Citizens who questioned that link were accused of selfishness. Political management had reached its final form, in which virtue and authority were synonyms.

By 2023, the moral vocabulary of the machine had conquered nearly every sector. Information integrity meant censorship. ESG investing meant political obedience disguised as ethics. Global partnership meant rule without consent. The administrative state that began with FDR’s paper files and Johnson’s slogans had finally merged with a digital empire managed by unseen moderators.

The stage was set for a counterreaction. Across social platforms, independent journalists began documenting the classified handshakes between tech executives and federal agencies. Court filings revealed internal emails coordinating what users could say. Congress, once irrelevant to administration, briefly caught up. The illusion of neutrality cracked. For the first time since the 1960s, Americans saw the system that claimed to protect them as a danger to self‑government.

That clarity would soon collide with electoral change. The backlash built quietly in the working economies of middle America and the independent corners of the internet. By 2024, the revolt had a name: the return of accountability. The same nation that once built the bureaucracy now prepared to measure it.

Trump 2.0 and the Battle Against the System

The election of 2024 was not a normal transfer of power. It was the moment the American electorate finally tested whether the system it created could still correct itself. The voters did not simply return Donald Trump to the presidency. They issued a direct challenge to the web of government, media, and finance that had spent eight years pretending to be the country’s conscience. The reaction proved how deep the capture ran.

By the time Trump retook the oath, the old establishment had already framed his presidency within the language of crisis. Networks spoke of “national division.” Pundits warned of “democratic backsliding.” Bureaucrats whispered about “preserving norms.” The same vocabulary used to sanctify overreach during the pandemic now worked as pre‑emptive justification for resistance.

Trump II began with a promise summed up by a short phrase: Make America Healthy Again. His alliance with Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was a strategic choice as well as a cultural signal, the return of cross‑party populism that both distrusted bureaucracy and valued bodily autonomy. Together they embodied a message the ruling class feared most: agreement between skeptics on the right and dissenters from the left. Within weeks of taking office, the administration launched reviews of pharmaceutical regulation, intelligence overreach, and federal censorship programs. Each investigation struck nerves that had been raw since 2016.

The Department of Government Efficiency, led by Elon Musk during its early months, targeted institutional waste with mathematical precision. Hundreds of inactive contracts and consultants were cut. Oversight reports revealed billions spent on research that duplicated existing programs or funded ideological campaigns. The backlash came instantly. Leaked emails warned of “attacks on science” and “anti‑government extremism.” For a workforce long accustomed to untested budgets, accountability looked like hostility.

The real collision took place in the communication sphere. Within the first year, the administration dismantled federal partnerships with social‑media companies that had enabled content censorship. New disclosure rules forced agencies to publish all contacts with media organizations concerning active investigations or public health messaging. The same journalists who championed transparency under Nixon and Bush now argued that too much sunlight endangered national security. Transparency, once a sacred word, became dangerous again.

Internationally, Trump II signaled the end of reflexive interventionism. Within months, he declared a ceasefire between Israel and Iran after U.S. precision strikes destroyed Iranian nuclear sites. The reaction revealed the split inside the American Right itself. Older neoconservatives accused him of weakness; younger conservatives saw it as the first responsible act of peace in decades. The result was unmistakable: foreign policy debates once dictated by think tanks returned to ordinary voters. For the first time in a generation, Washington had to explain wars before funding them.

Economically, the administration rolled out what it called a “re‑industrialization compact.” Tax credits and regulatory relief within the energy and manufacturing sectors drew businesses back to the interior states. Average fuel costs declined, inflation slowed, and private manufacturing job numbers improved for the first time in years. Yet the federal bureaucracy, especially within environmental and labor departments, fought every line of reform with procedural delay. Regulations already struck from the books reappeared under new names. The administrative state behaved like an immune system rejecting transplantation.

The most controversial initiatives were the audits. The new Office of Federal Integrity published findings on agency contracting, media partnerships, and the revolving door between regulators and corporate boards. Dozens of senior officials resigned before hearings began. Investigations exposed how federal grants had financed non‑government organizations that later became campaign donors. For the public, these revelations were jarring but not surprising. For the institutions, they were existential threats.

The counterattack came through familiar instruments: lawsuits, leaks, and moral panic. State attorneys general coordinated cases to block federal reforms. Former officials portrayed every downsizing effort as “political retribution.” Media coverage returned to the language of apocalypse. Columns predicted the “collapse of democracy” every week that spending declined. In truth, what collapsed was the illusion that bureaucracy belonged to no one.

For ordinary Americans, the second Trump presidency has already proved one point: when government faces accountability, it behaves like a cornered monopoly. Every attempt to enforce transparency meets claims of persecution. Every exposure of waste becomes “anti‑science.” Transparency itself becomes radical. That inversion of moral terms, turning honesty into extremism, is the final defense mechanism of a captured system.

Whether Trump can fully dismantle that system is uncertain. Power this entrenched does not yield easily. But the mere act of confronting it has revived something that Washington spent decades suppressing: the idea that citizens have the right to know how they are governed. The political class that survived on managed decline now faces a public that finally demands measurable results.

History shows that real reform begins only when institutions lose their moral immunity. Roosevelt expanded bureaucracy through compassion. Johnson sanctified it through equality. Clinton privatized it through efficiency. Obama idealized it through progress. Biden globalized it through safety. Trump’s second administration is the first in a century to confront it on the single battlefield it always avoided: the truth.

What Comes After the System

Every civilization reaches a moment when it must choose between honesty and convenience. America has arrived. A century of moral politics built a machine so large that many have forgotten what existed before it: government as lifestyle, media as priesthood, education as obedience training. The outcome is visible everywhere: debt without limit, words without meaning, leadership without humility. The question now is whether citizens still believe they can rebuild something smaller, harder, and truer.

Trump’s second presidency marks a political correction, but lasting change must come from below. Bureaucracies reform only when people stop feeding them. The future of accountability depends less on new laws than on revived competence: citizens who can feed themselves, teach their children, and defend their digital and physical lives. A population skilled in self‑reliance cannot be ruled by advice. That was once the American norm; it can be again.

To rebuild, three facts must be accepted.

First, freedom requires friction.

Comfort breeds obedience. When safety replaces duty, maturity disappears. Independence means risk: businesses failing and rising without bailout, parents reclaiming education without permission, and communities policing themselves when central government falters. A free nation endures uncertainty rather than surrendering responsibility.

Second, truth must return to the local scale.

National media made facts plentiful and trust scarce. The cure for manipulation is not more information but proximity. Local journalism, open school boards, and direct civic verification will accomplish more than ideological debate. Perspective shrinks falsehood. Clarity begins where people can still look one another in the eye.

Third, virtue must become measurable.

Modern politics confused emotion with ethics. “Caring” replaced doing. Compassion enforced by power is cruelty with better manners. Justice without humility is control. True virtue produces results that can be seen, strong families, honest work, clean streets, and stability. Any policy that fails those tests, no matter how benevolent the slogan, is failure.

Every lasting reform starts with moral realism: the recognition that no elite will regulate itself out of power. The modern myth of “expert rule” rests on fear that citizens cannot manage their own lives. That fear built the clerical bureaucracy we call the managerial state. Ending it requires a restoration of humility among both rulers and ruled, the understanding that perfect knowledge does not exist, and that freedom begins where expertise ends.

Technology adds its own challenge. Artificial intelligence, automation, and digital finance can either centralize control or empower individuals, depending on who learns faster. When citizens master technology before regulators do, decentralization wins. The task is moral, not mechanical: using intelligence and innovation to strengthen honest work instead of replacing human purpose.

Younger generations hold a quiet advantage. They see the failures of credentialed authority firsthand. They trust almost nothing, which is dangerous if it curdles into despair, but invaluable if it becomes disciplined skepticism. What they need is an ethic of competence, a joy in fixing what is broken rather than merely denouncing it. Skills are freedom in tangible form.

America’s founders assumed that freedom, corruption, correction, and renewal would cycle forever. For decades, that rhythm paused in the second stage, corruption defended by sentiment. The moment of correction has returned. It will not resemble protests or parades; it will look like small laboratories of honesty rebuilding from the ground up: families regaining stewardship, churches restoring charity to human scale, local industries defying monopolies, neighbors judging truth among themselves rather than through screens.

No ruler can force virtue. Liberty survives only through people who choose responsibility over comfort, reality over narrative, and effort over entitlement. Revolutions of hashtags or committees achieve nothing; craftsmanship in conduct changes everything. Personal excellence, multiplied, is the one kind of rebellion a bureaucracy cannot predict.

When the Left Wins, You Lose has never been simply partisan. It is a moral diagnosis. The structure that calls itself progress is dying of its own conceit, that morality can be engineered and virtue outsourced. Through its fractures, a familiar light is visible again: the dignity of citizens who fix rather than watch.

If America remembers that honor, it will not merely endure. It will deserve to.

The Return of the Citizen

This essay traced how a free republic drifted into bureaucratic rule. The story was never about parties alone. It is about a transfer of power from voters to institutions, from accountability to morality, from citizens to managers.

Once government learned to treat “compassion” as a blank check, the rest followed naturally. Programs became permanent. Bureaucracies became self-protecting. Media became enforcement. Expertise became a substitute for consent. The system did not need to win every election because it learned how to outlast elections.

Trump’s return did not create that conflict. It exposed it. When voters threaten institutional privilege, neutrality evaporates. The point of the last decade was not that these tools exist. It is that they were used openly, and in doing so, they revealed what the country had become.

So the question is no longer whether the machine is real. The question is whether citizens still want to be citizens.

This is not a call for nostalgia. It is a call for recovery. Local control instead of bureaucratic dependence. Personal responsibility instead of managed virtue. Voluntary cooperation instead of enforced consensus. The road back does not start in Washington. It starts where people still have skin in the outcome: households, congregations, small businesses, and communities willing to take responsibility for their own decisions.

A nation does not collapse because its leaders lie. It collapses when its people accept the lie as normal.

If Americans rebuild trust through transparency, competition, and courage, the old rhythm returns: corruption, correction, renewal. If they do not, democracy becomes theater and citizenship becomes a costume worn once every four years.

The purpose of this work was not despair, but clarity. A nation that can name its illness is still alive enough to heal. The remedy will not come from a savior, a slogan, or a subsidy. It will come from citizens who insist that words mean what they say, laws apply equally, and truth outranks narrative.

History does not end with bureaucracy. It ends only when people forget that they are free.

Remembering is the first act of recovery.

If This Matters, This Is Your Moment

I will keep writing either way. The question is whether this stays survival mode or becomes something that can grow and endure. I am not asking for sympathy. I am describing incentives: unfunded work does not compound.

To everyone already supporting this: thank you. If you believe this matters, this is the moment.

Great work. The emphasis on the "advice of the expert class" carries weight from the New Deal all the way through to DAVOS and the "Great Reset," all promoted by "experts." Two things I am reminded of; one, the words of Thomas Sowell when he talks about the diffusion of knowledge spread out among many individuals. The second is the incredulous decent of Ms. Ketanji Brown Jackson concerning the SCOTUS dismissal of "expert guidance."

I recommend the book, The Death of Common Sense: How Law is Suffocating America by Philip K. Howard. Though the book was published in 1995, it is even more relevant today. In reading it, I learned of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) of 1946, which effectively gave rules and regulations, crafted by unelected bureaucrats in Federal agencies, the power of law.