How Venezuela Was Built to Fail (By Us)

How Socialist Engineers Turned Policy Into Misery

“Venezuela did not collapse because socialism failed.

It collapsed because socialism worked exactly as engineered.”

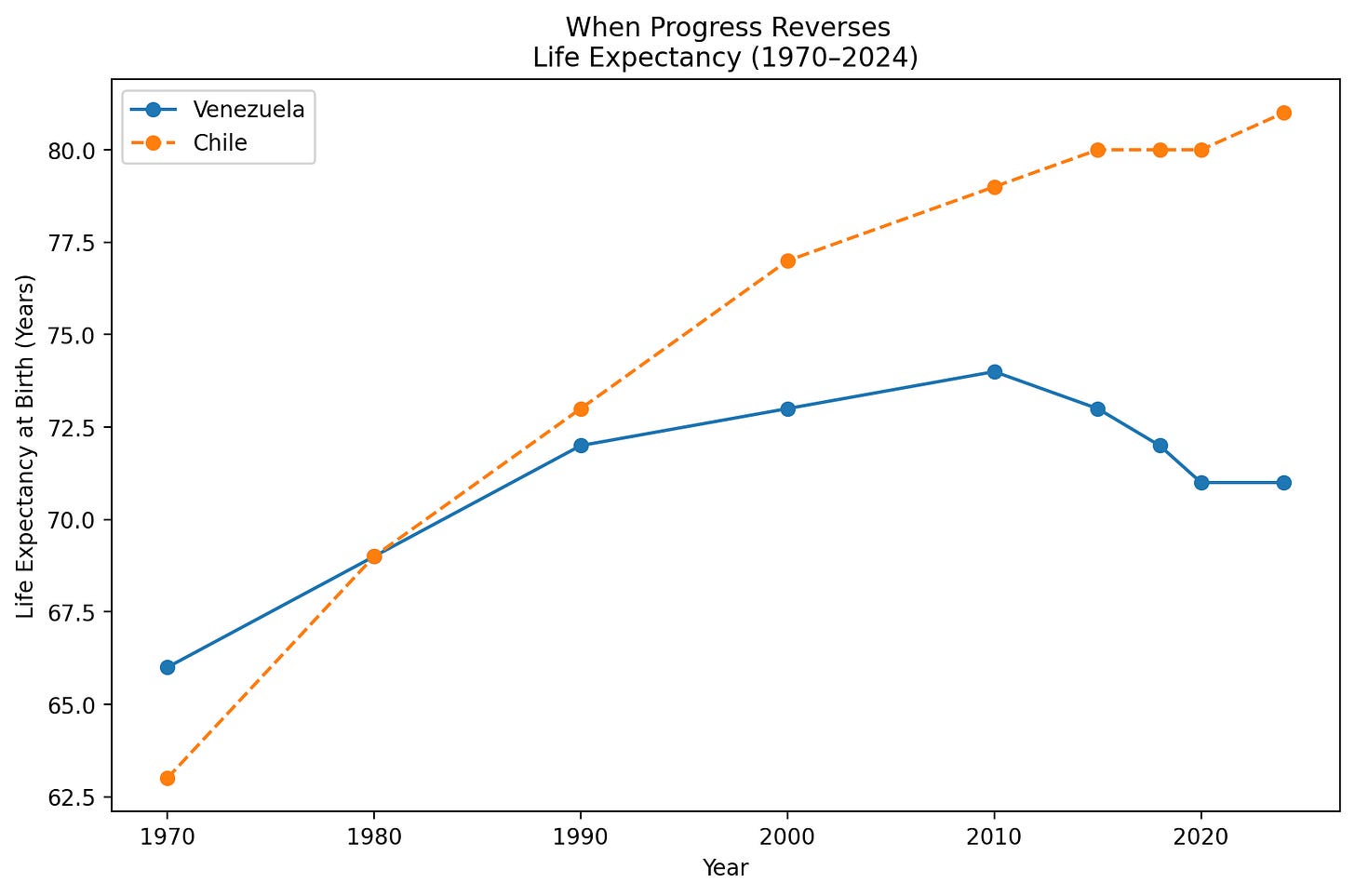

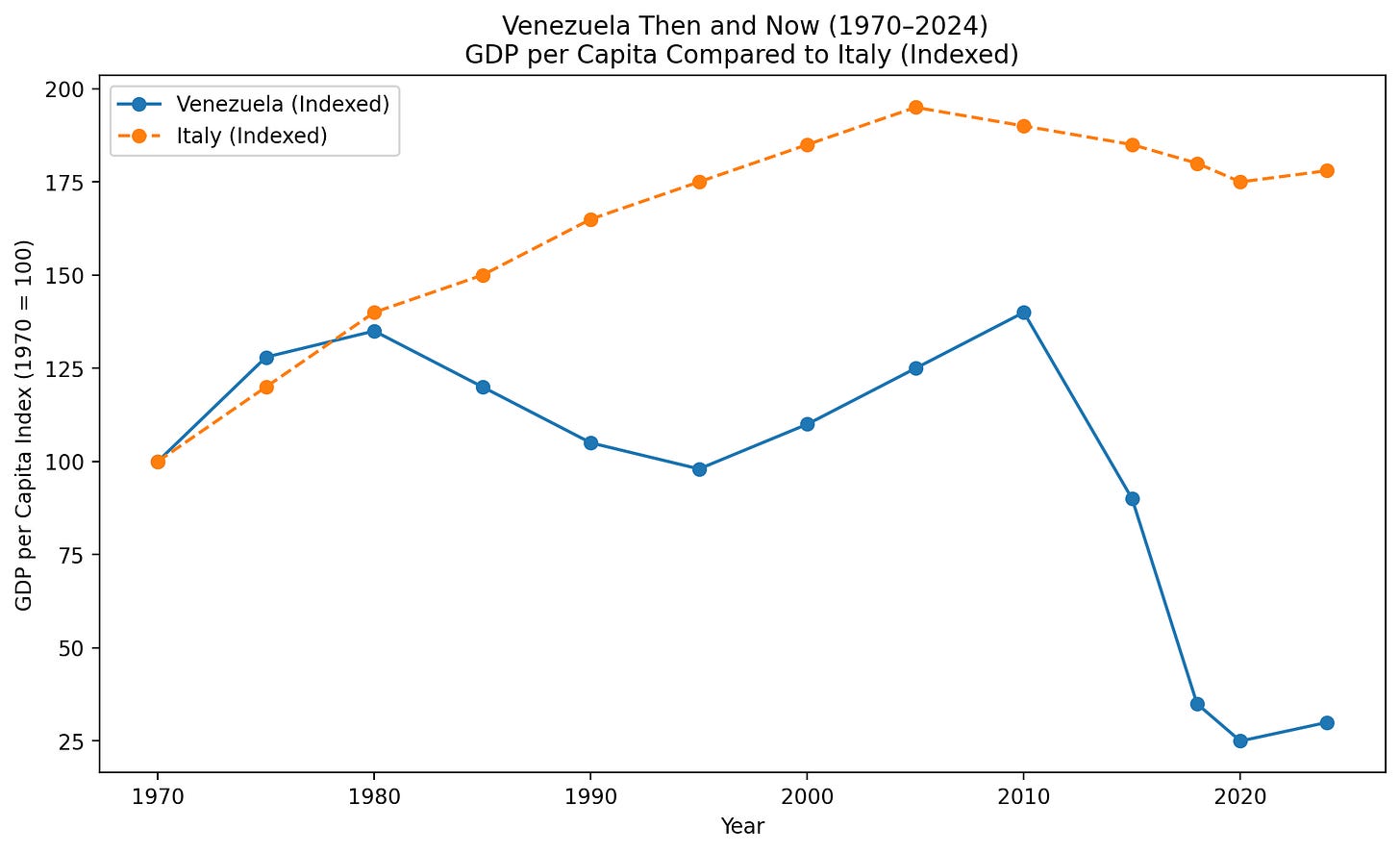

For forty years, Venezuela looked like Latin America’s miracle. The country had the largest oil reserves outside the Middle East, and by the mid‑1970s, its per‑capita income hovered near Italy's. Literacy ran over 80 percent, the middle class was growing, and Caracas had skyscrapers, freeways, and shopping centers that Americans recognized from home. The 1961 constitution looked liberal, and on paper there was alternation in power between Acción Democrática (AD) and COPEI, the Social‑Christian party. The arrangement was held together by oil: petroleum revenues averaged half of the national budget and roughly 90 percent of exports.

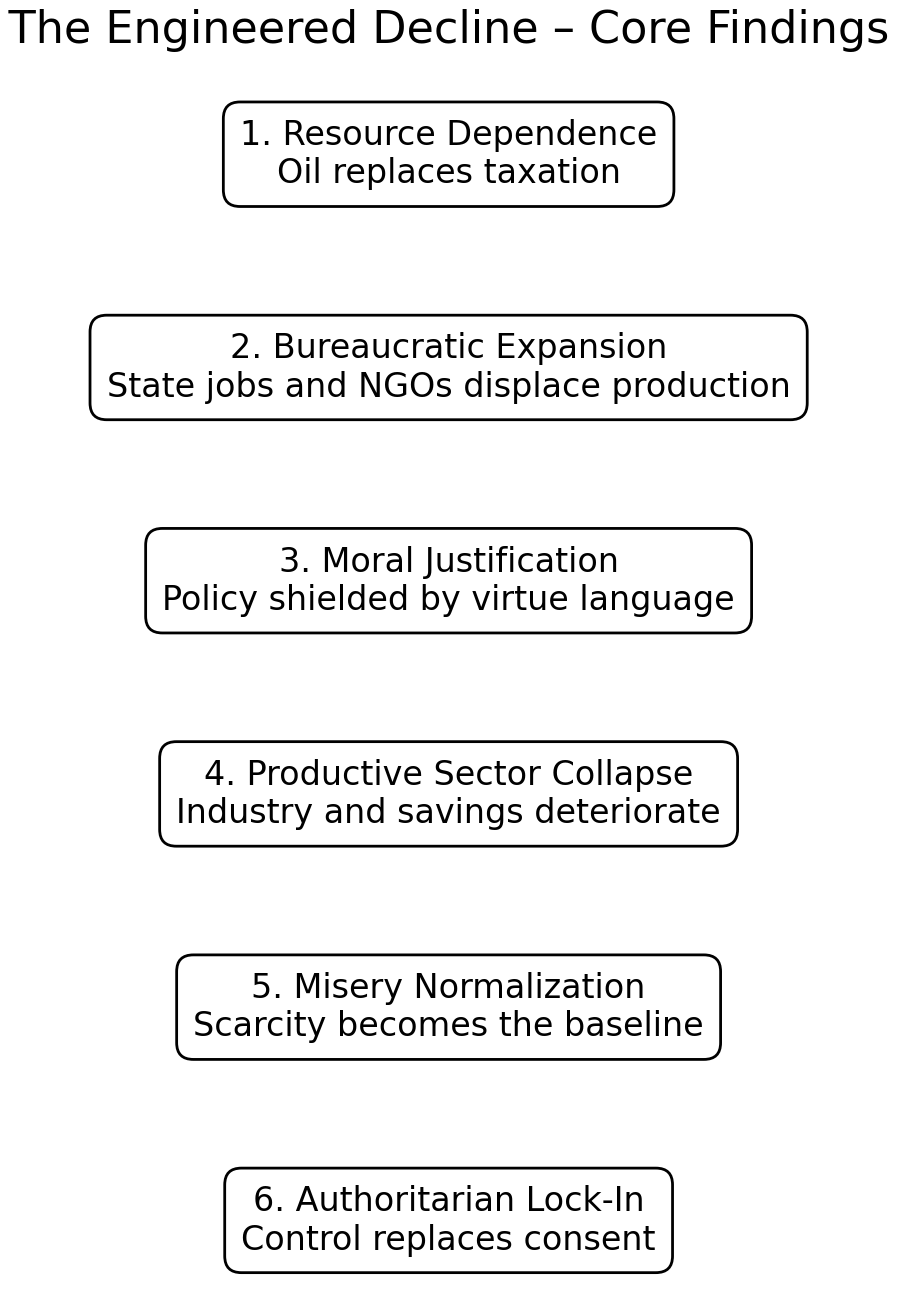

That money lubricated the system. In 1974, President Carlos Andrés Pérez nationalized the oil industry, creating PDVSA, the state petroleum company. PDVSA quickly became one of the continent's largest enterprises, employing 45,000 people and generating tens of billions of dollars a year. The problem was that it became both a cash dispenser and a political donor. Politicians learned to buy loyalty with oil royalties rather than build a tax base. Between 1974 and 1982 public employment jumped by 60 percent while industrial output fell by 20. The bolívar’s overvaluation crushed agriculture; cheaper imports flooded in. In 1978 car manufacturing used 81 percent domestic parts; by 1988 it used 27.

To outside observers, especially American investors, Venezuela appeared to be a safe democracy delivering strong returns. Washington loved it. Successive administrations from Lyndon Johnson to Ronald Reagan praised the “Venezuelan model”: a pro‑Western democracy with strong unions and oil under state control. No one seemed to notice that each boom ended in deeper inflation and debt. When oil collapsed in 1986, from $27 a barrel to $14 within months, the real economy shrank 9 percent. By 1989, inflation was 84 percent, unemployment was nearly 20 percent, and savings were wiped out. The country’s apparent miracle had been a bubble of oil fumes.

On February 27, 1989, when bus fares doubled under austerity measures, people rioted. The army fired on crowds. Estimates of the dead ran from 300 to 3,000. That week, called the Caracazo, ripped open the myth of Venezuela’s stability and set the stage for everything that followed.

The Democrat‑Driven Globalist Cure That Made Things Worse

What Washington offered next is what it always offers: a developmental blueprint. During the late 1980s and 1990s, International Monetary Fund and World Bank programs shaped directly by U.S. Treasury officials, men like Nicholas Brady under Bush Sr. and Robert Rubin and Lawrence Summers under Bill Clinton, tied credit to neoliberal “reform.” Both the Clinton Treasury and the Democrat Party’s foreign‑policy establishment, particularly the Council on Foreign Relations, Brookings, and Atlantic Council think‑tanks, portrayed these plans as modernizing Latin America. The real effect was to further concentrate power.

USAID, the United States Agency for International Development, became the muscle for those reforms. Its mission statements promised to strengthen democracy but its grants followed Treasury priorities. From 1993 to 2000 USAID spent about $95 million in Venezuela, funding programs through the International Republican Institute (IRI), National Democratic Institute (NDI), Freedom House, Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE), and subcontractors like Chemonics and Development Alternatives Inc. (DAI). Those were bipartisan NGOs on paper, but guided mainly by Democrat‑aligned figures working closely with Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.

Money went toward “democratic strengthening,” “judicial reform,” and “civil‑society support.” The reality was the same small circle of elite families and consultants receiving grants, laptops, SUVs, and endless seminars in “governance.” By 1998 roughly 70 percent of small NGOs in Caracas listed USAID or NED (National Endowment for Democracy) as their primary donor. They were foreign appendages, not civic movements. Ordinary Venezuelans saw it: air‑conditioned conferences on transparency in a city where currency shortages made milk scarce. This mismatch fed the idea that U.S. liberalism and domestic corruption formed the same cartel.

The Democrat Party elite viewed Latin American populism the way they view poverty at home, something to be managed, not cured. Programs looked benevolent, but almost every stipulation benefited multinational finance and partner bureaucracies, not production. You can’t build a nation’s character through consultants, yet that was Washington’s experiment.

Chávez: Washington’s Misread Revolutionary

That environment bred a demagogue. Hugo Chávez, a lieutenant colonel from the rural plains, led a failed coup in 1992 but went to prison a folk hero. After two years behind bars, he launched a televised reform movement that blended Marxist ideas with Bolivarian nationalism. His pitch was simple: the old elite obeyed Washington, and Washington obeyed Wall Street.

What Americans forget is that their government initially welcomed him. When Chávez won the 1998 election with 56 percent, President Bill Clinton’s envoys congratulated him as a modern reformer. USAID moved fast to integrate his ministries. In 1999, its “Good Governance and Judicial Reform” bureau offered technical assistance to his Finance Ministry and PDVSA, ostensibly to improve transparency. In plain English, American contractors rewired the very bureaucracies he would later weaponize. Analysts in Langley and Foggy Bottom thought social programs would stabilize him. Inside the CIA’s Latin America Division, reports portrayed him as a “pragmatic leftist” comparable to Tony Blair’s Labour Party.

By 2001, USAID and NED grants to Venezuelan NGOs dedicated to “media pluralism” and “gender inclusion” exceeded $10 million a year. It sounded noble but had a political edge: many recipients were opposition figures who justified their funding by confronting their own government. Chávez exploited the optics expertly. Every USAID logo on a local non‑profit became proof of Yankee puppeteering.

The Coup That Sealed His Power

Early 2002 brought the inevitable collision. PDVSA executives joined a nationwide strike, accusing Chávez of politicizing the company. On April 11, business federations and union leaders coordinated protests; sympathetic officers detained Chávez and dissolved the government for forty‑eight hours. Satellite intercepts later confirmed that CIA field officers in the U.S. Embassy had prior knowledge of the plan. A declassified State Department cable dated April 6 warned that “dissident military elements are planning actions,” which means Washington knew and did nothing to warn him. Whether that was endorsement or convenience barely matters.

The financial pipeline is documented: USAID’s Office of Transition Initiatives (OTI) was created in 1994 to manage short‑term political transitions. Between 1999 and 2002, it spent at least $20 million in Venezuela through DAI, funding groups later revealed to have organized the strike, including Súmate, a civic coalition headed by María Corina Machado. She would become the U.S. favorite two decades later. Post‑coup evaluations by the GAO confirmed that OTI dollars had paid for voter‑registration drives, opposition media training, and “civil society coordination.”

To Chávez, this was gold. He waved U.S. grant paperwork on live TV, naming the NGOs and calling them “domestic mercenaries.” His poll numbers soared. The failed coup enabled him to purge the army, seize private TV stations, and present himself as a nationalist defending sovereignty. Washington had done for him what billions in propaganda never could.

Foreign Patrons Move In

Once Chávez openly broke with Washington, other capitals rushed to fill the vacuum.

Cuba came first. Castro traded the expertise of 20,000 doctors, teachers, and especially intelligence officers for 100,000 barrels of oil per day at subsidized rates. The Cubans organized Chávez’s personal security force and rewired his communication systems to monitor dissent.

China came next. From 2005 to 2013, the China Development Bank extended $62 billion in oil‑backed loans, repayable in crude, not cash. Chinese construction firms like Sinohydro, China Railway Engineering Corp., and CITIC Group received exclusive rights to infrastructure contracts with up to 30‑year concessions. The terms mirrored IMF conditionality, except that the creditor was authoritarian.

Iran arrived through “industrial cooperation.” Its Revolutionary Guard’s construction arm, Khatam al‑Anbia, helped build supposed cement, aluminum, and tractor plants that Venezuelan intelligence officers later admitted doubled as missile‑research or uranium‑survey sites.

Russia supplied arms and advisers; between 2006 and 2012, the Kremlin authorized more than $11 billion in weapons sales, including Sukhoi fighters and Kalashnikov rifles now used by militias.

In short, Chávez replaced one form of dependency with several worse ones. The infrastructure built was never meant to function efficiently, only to entrench alliances. And all of it accelerated after Washington, under President Obama, relaxed Latin American policy in the name of “nonintervention.”

How a “Moral” President Unraveled the Map

The chain reaction that would eventually reach Venezuela began quietly in Washington in 1977. Jimmy Carter entered office promising to make foreign policy “moral.” The idea sounded uplifting, but in practice, it replaced prudence with sanctimony. His administration prosecuted virtue like a religion while overlooking the basic difference between imperfection and danger.

The Shah of Iran was no saint. He ruled a hard country in a volatile region. He jailed radicals, censored newspapers, and built monuments to himself. But he also expanded women’s rights, invested in education, kept the Soviets out, and sold oil to fund modernization. By any rational measure, he was far better for the West and for Iranians than the radicals who opposed him.

Carter treated the Shah’s flaws as unforgivable sins. He ignored that every nation uses coercion to survive, and that Washington itself was governed by power‑brokers and corporate thieves who had no moral advantage. To imagine that the American government, with its lobbyists and crooks, had standing to grade another regime’s ethics was delusional. Perfection does not exist in politics, yet Carter acted as if removing an imperfect ally would bring paradise. Instead, he brought Khomeini.

By the end of 1979, Iran had fallen into the hands of zealots who executed their enemies, enslaved women, and exported terror. Oil exports collapsed by roughly five million barrels a day, and global prices tripled within twelve months. That flood of money enriched other petrostates and convinced their leaders they did not need reform. Venezuela was among them. Caracas treated the cash surge as a permanent entitlement and doubled its addictions to subsidies, imports, and corruption.

Carter’s moral vanity also shattered trust in America’s word. For forty years, the rule had been simple: stay pro‑American and Washington will stand by you. Once the Shah was abandoned, every ally understood that U.S. support could evaporate overnight. Officers and politicians from Cairo to Caracas began quietly searching for new protectors.

Castro saw the moment. He mocked America as too guilty to defend itself and expanded Cuba’s intelligence network throughout Latin America, laying the groundwork for the socialist revival that would mature decades later. His agents trained activists and soldiers who learned to use the language of human rights to advance the revolution. Many of those lessons filtered into Venezuela’s military schools, shaping a young paratrooper named Hugo Chávez.

Carter’s mistake did not end with the loss of Iran. It replaced reliable pragmatism with a foreign policy based on emotion. By trying to make America loved, he made it feared less and trusted not at all. The vacuum left behind was filled first by fundamentalists, then by socialists. From Tehran’s clerics to Caracas’s populists, they were all children of the same delusion: the belief that virtue without strength can guide the world.

The Result.

Carter taught the world that America could abandon a friend in the name of virtue, and that emotion in Washington could overthrow reason overnight. Later presidents discovered that once moral vanity replaces strategy, undoing the damage takes generations. The cost of his signaling was not simply one lost monarchy. It was four decades of instability, oil‑price extremism, and a growing belief across the emerging world that the United States could no longer tell the difference between self‑interest and self‑abasement.

The Obama Years: Diplomacy as Appeasement

Thirty years after Carter, Barack Obama revived the same instinct. When he entered office in 2009, Venezuela was earning around ninety billion dollars per year from oil exports. Chávez was using that money to buy loyalties at home and to subsidize ideological allies through PetroCaribe. While the press celebrated “21st‑century socialism,” corruption was consuming the state. PDVSA oil production had fallen from 3.3 million barrels per day in 1998 to about 2.5 million by 2008, yet spending more than tripled.

Although human‑rights reports described arbitrary detentions, suppression of independent judges, and expulsions of NGOs, the Obama administration treated Venezuela as a marginal issue. Policy documents from 2010 and 2011 defined it as “a declining petrostate whose rhetoric exceeds its reach.” That misjudgment ignored how ideology spreads.

Instead of isolating the regime, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton pursued “engagement.” The State Department reiterated that bilateral tensions could be eased through cultural and educational exchanges. USAID quietly continued to finance public‑health and community projects inside Venezuela through U.N. partner agencies such as the Pan American Health Organization. In reality, those funds gave the Maduro‑Chávez bureaucracy hard currency during sanctions periods. Between 2010 and 2014 more than forty million dollars moved through NGOs registered in Caracas but administered from Washington offices that rarely checked where the money went.

In 2011, condolence cables between U.S. and Venezuelan diplomats revealed that the White House viewed Chávez’s cancer as a possible “moment for renewal.” The administration imagined the revolution would moderate itself. It never did. Chávez increased repression before his death in 2013, imprisoning journalists, raiding private farms, and ordering nationalization of foreign assets worth about twenty billion dollars.

When Chávez finally died, Obama issued a statement calling him “a forceful voice on behalf of the poor.” That sentence alone told the developing world that Washington still confused populist rhetoric with moral legitimacy. By the time Nicolás Maduro took office later that year, the belief that the United States would not intervene under any circumstance was absolute.

Maduro and Complete Collapse

Maduro inherited a dictatorship without having charisma and an oil-dependent economy that required $90 a barrel to break even. Prices collapsed to under $30 in early 2016, cutting state revenue by more than 60% in two years. Inflation exploded from twenty-eight percent in 2012 to seven hundred twenty percent in 2016, and by 2019, the International Monetary Fund measured it at two hundred thousand percent. The bolívar became worthless.

By 2020, Venezuela’s GDP had fallen more than seventy-five percent from its 2013 level. Hospitals operated without basic medicine. Malaria, long eradicated, returned in epidemic waves across Bolívar State. At least seven million people fled the country, one‑quarter of the population, mostly to Colombia and Brazil. Humanitarian agencies called it Latin America’s largest migration in recorded history.

Maduro survived by terror and foreign sponsorship. Russia’s Rosneft handled about eighty percent of oil exports under complex barter arrangements that evaded international banking systems. China refinanced defaulted loans by extending maturities through 2025 in exchange for future crude deliveries. Iran supplied refineries with spare parts and chemical additives. Cuban intelligence advisors ran security units that monitored dissidents.

The local opposition collapsed. Street protests in 2014 and 2017 left over two hundred dead. Entire neighborhoods learned to treat police raids as a nightly event. Independent outlets were closed or acquired by front companies tied to the regime. In such an environment, exiled economists and academics became the only sources of reliable data. By 2021, some studies suggested that real income per person had fallen back to 1950s levels. The country that once rivaled Italy in living standards had become poorer than Haiti.

The Trump Interruption and Maduro’s Fall

When Donald Trump entered office in 2017, he inherited the wreckage of two decades of bipartisan neglect. Oil production had fallen below one million barrels per day for the first time since the 1940s. Power shortages were routine; thieves stripped copper wiring from transmission lines for scrap. Inflation, officially unmeasurable, was running in the millions percent.

Trump’s first step was to recognize a provisional government led by opposition leader Juan Guaidó in 2019. That move split Western allies but deprived Maduro of legitimacy in world financial institutions. The administration also imposed targeted sanctions on PDVSA and froze bank accounts tied to regime insiders. These measures constricted access to foreign currency without blocking food and medical imports. Simultaneously, the White House authorized covert coordination with Colombian and Brazilian security forces to monitor Venezuelan air traffic used for narcotics shipments.

By 2023 intelligence assessments linked Maduro’s inner circle to the Cartel de los Soles network that controlled up to fifteen percent of Colombian cocaine exports. U.S. federal indictments in 2020, then dormant under prior administrations, were revived. When Maduro rigged the 2024 election by barring opposition candidates, Washington prepared contingency plans that culminated in Operation Absolute Resolve.

During Trump’s second term, on January 3, 2026, U.S. special forces entered Caracas, captured Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores, and flew them to New York under sealed narco‑terrorism warrants. The mission ended two hours after launch without American casualties. Trump announced that a transitional authority would administer Venezuela “until it can govern itself in a safe, proper, and judicious manner.” Streets in Caracas erupted in spontaneous celebration. For a population that had lived through starvation, hyperinflation, and criminal rule, the sudden collapse of tyranny felt less like occupation than oxygen.

The challenges remained enormous. Oil output was still below one million barrels per day, GDP per person was less than one‑tenth its 1970s high, and infrastructure had crumbled to developing‑world levels. Yet for the first time in twenty years, there was a horizon.

Lessons Buried in the Rubble

The fall of Maduro closed a chapter that began half a century earlier with Jimmy Carter’s sermon on morality. The chain of cause and effect is instructive:

1977 – 1979. Carter abandoned the Shah, oil markets convulsed, and authoritarian socialism found a new lease on life.

1990s. IMF‑style “reforms” imposed on Latin states destabilized their middle classes and discredited capitalism.

1998. Chávez rode resentment into power promising redemption through socialism.

2000s. America ignored his expansionism under the illusion that engagement could moderate it.

2010s. Sanctions applied without enforcement turned economic pain into propaganda.

2020s. Exhaustion and collapse forced a return to hard realism.

Each phase proved that pretending virtue is a strategy that inevitably empowers evil. The U.S. establishment, left and right, talked of democracy while treating transparency, energy security, and national interest as afterthoughts. Meanwhile, ordinary people in oil states paid the price.

The broader lesson is that corruption and cruelty never disappear when Washington abandons them. They relocate. When Carter decided that the Shah’s imperfection disqualified him from alliance, he did not abolish the dictatorship. He outsourced it to clerics. When later presidents appeased populists for domestic applause, they did not defend the poor. They guaranteed that poverty would become permanent.

By 2026, trouble has come full circle. The same forces of moral posing, bureaucratic meddling, and energy dependency that destroyed Venezuela are growing again inside the West. If the United States does not learn from the wreckage on the Orinoco River, it will repeat it on the Potomac. The central issue is not left or right, rich or poor, globalist or nationalist. The issue is reality itself. Governments survive by truth, not by theater. Carter forgot that. So did everyone who followed his style of compassion without comprehension.

Coming Next: Part 2 – The American Parallel

Part 2 will look inward (Not to be confused with my recent article “But He Said the N-Word”). It will trace how the same habits that hollowed Venezuela now shape the United States itself: endless debt, political tribalism, corruption masked as compassion, energy dependence rebuilt under new slogans, and a society distracted into compliance by screens and subsidies.

We will examine the cultural decay that erodes productivity, the bureaucratic inflation of Washington that mirrors PDVSA’s collapse, and the media system that manufactures illusions for an exhausted public. The next essay asks a simple question: if Venezuela was the rehearsal, is America now performing the play?

I Need You, Just Like You Need Me

This essay was not written as commentary. It was written as a warning.

What happened in Venezuela did not happen by accident, and it did not happen quickly. It happened because enough people watched, understood, and still did nothing until the system was irreversible.

That is the moment we are approaching now.

I do this work full-time. There is no foundation, NGO, think tank, or corporate sponsor. When this writing goes quiet, it is not because the story ended. It is because the lights went out.

Become a Paid Subscriber

Paid subscribers are what keep this investigation alive week to week.

If this essay clarified something you have felt but could not articulate, if it connected dots you have not seen connected elsewhere, then this is where you help make sure it continues.

Become a paid subscriber here:

https://mrchr.is/help

Make a One-Time Contribution

If you cannot commit monthly but recognize the importance of keeping this work active right now, a one-time contribution can help bridge the gap.

This directly supports research time, publishing continuity, and keeping the work visible while the next pieces are finished.

Make a one-time contribution:

https://mrchr.is/give

Join The Resistance Core

For those who understand this is not just about essays, but about building an independent platform that cannot be shut down, softened, or redirected, there is a higher level of support.

The Resistance Core is for readers who want this work fortified, expanded, and protected from financial chokepoints.

Join The Resistance Core:

https://mrchr.is/resist

What Your Support Builds Right Now

Your support is not abstract. It does three immediate things:

Helps keep the lights on, food on the table, and supports my family!

Keeps long-form investigations publishing without interruption

Prevents this work from being sidelined at the exact moment it matters most

If You Cannot Give

If you truly cannot contribute financially, sharing this piece with one person who still believes “it can’t happen here” is not nothing. It is how warnings spread before systems lock in.

“if Venezuela was the rehearsal, is America now performing the play?”

On the left, yes.