Misery Loves Company: Why Big Cities Always Turn Blue

How Democrat Policies Turn Density into Dependency and Dependency into Votes.

Last week, Brandon Tatum posed a simple but important question on his show: Why do big cities always turn blue? The question itself stayed with me because no one ever seems to answer it fully. I have thought about it for years, watching city after city follow the same path. His remark was the spark for this essay.

Where Growth Turns to Decay

Name one major American city that became safer, cleaner, and more functional as it grew, while the Democrat Party became more entrenched. Just one. You cannot.

The evidence is everywhere. Cities expand, taxes rise, disorder spreads, and government grows. Each decade brings new programs to address the problems created by the previous set. The more help citizens receive, the less responsibility they carry. What follows is not progress but managed decline.

This pattern does not owe its existence to geography or industry. It comes from incentives. When people cluster in large numbers, personal accountability breaks down. Rules and regulators replace trust. The system begins to reward dependency and punish initiative. Political power collects wherever dependency collects.

For more than sixty years, the pattern has repeated. From New York to Los Angeles, from Chicago to Austin, the larger the city becomes, the deeper its reliance on bureaucratic authority. Voters respond to fear and instability by demanding protection, and the party offering ever‑larger government always wins.

Freedom contracts while control expands. Disorder becomes a source of employment for administrators and politicians alike. Those who create dependency end up owning it.

From Self‑Reliance to State Reliance

For most of American history, cities were places of enterprise, not therapy. People moved to them because work was available and achievement was rewarded. The city symbolized opportunity. What changed was not population count alone but the way incentives were rearranged as government power expanded to manage the side effects of growth.

Small towns function on reputation. A person known for dishonesty, idleness, or violence finds little refuge when everyone remembers yesterday’s mistakes. In such environments, self‑discipline and mutual obligation preserve social order. A man’s word, and sometimes the local sheriff, are enough. That structure collapses in modern cities, where anonymity and distance make government the first recourse instead of the last. What neighbors once handled together—safety, charity, discipline—is now outsourced to salaried strangers with titles.

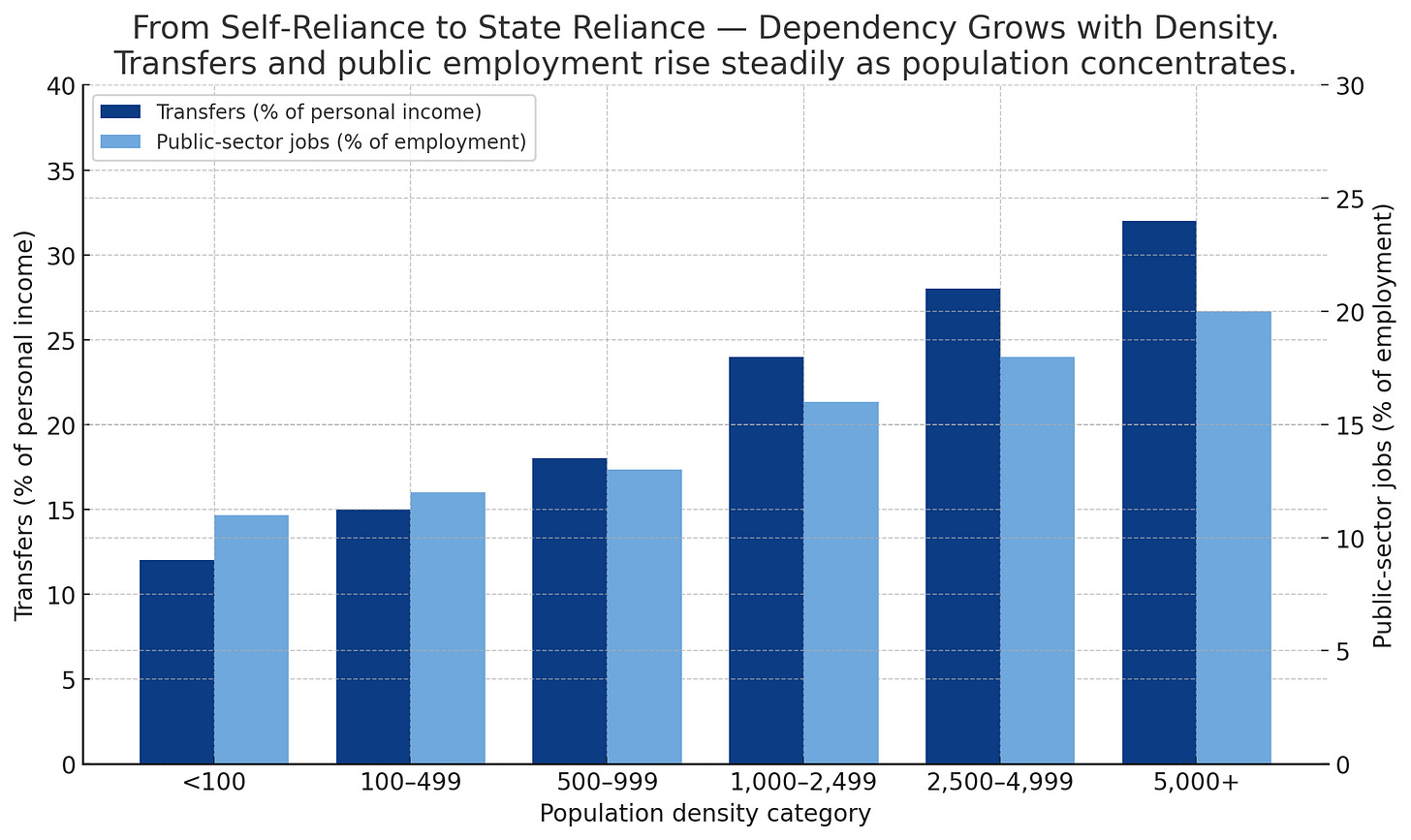

Over time the substitution becomes habit, then ideology. The idea that government should manage every difficulty transforms from an emergency measure into a way of life. The data confirm it. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2024 American Community Survey, federal and state transfer payments accounted for nearly 30 percent of total personal income in the ten largest metropolitan areas, compared with 18 percent in non‑metro counties. In Los Angeles and Chicago, more than 22 percent of households received some form of public assistance beyond Social Security—housing vouchers, SNAP, or cash welfare. This shift changed not only how people live but how they vote.

Historically, high‑employment cities such as Detroit or Cleveland voted Republican well into the first half of the twentieth century. Their voters worked in factories, owned homes, and feared government interference more than corporate exploitation. As industry declined and welfare programs expanded during the Great Society era, both cities flipped. Today, every one of the twenty largest U.S. cities votes Democrat by margins exceeding 65 percent, and each has welfare usage rates higher than the national average.

The pattern is visible in Texas as well. Austin, still celebrated for its technology sector, now devotes more than 41 percent of its municipal budget to “social services and public health initiatives,” up from 23 percent just a decade ago. During the same period, violent crime increased by over 25 percent, and average property taxes rose by nearly 40 percent. The growth of dependency did not solve the problems it was meant to address; it institutionalized them.

City administrators call this progress. In reality, it is the quiet exchange of freedom for management. Each new subsidy, safety net, or community program weakens the habits that once made independence both possible and expected. Where voluntary order fades, bureaucratic order expands. Each additional grant, office, and commissioner creates its constituency.

Power always follows the money, and in modern cities the money follows dependency. The end result is not prosperity evenly shared but responsibility evenly avoided.

Power grows where dependency grows.

The Economics of Dependence

Money does not only buy goods; it buys habits. Once a city learns to live from public revenue rather than private productivity, its people and its politicians adjust their expectations to the same rhythm. Dependency ceases to be a symptom and becomes the system itself.

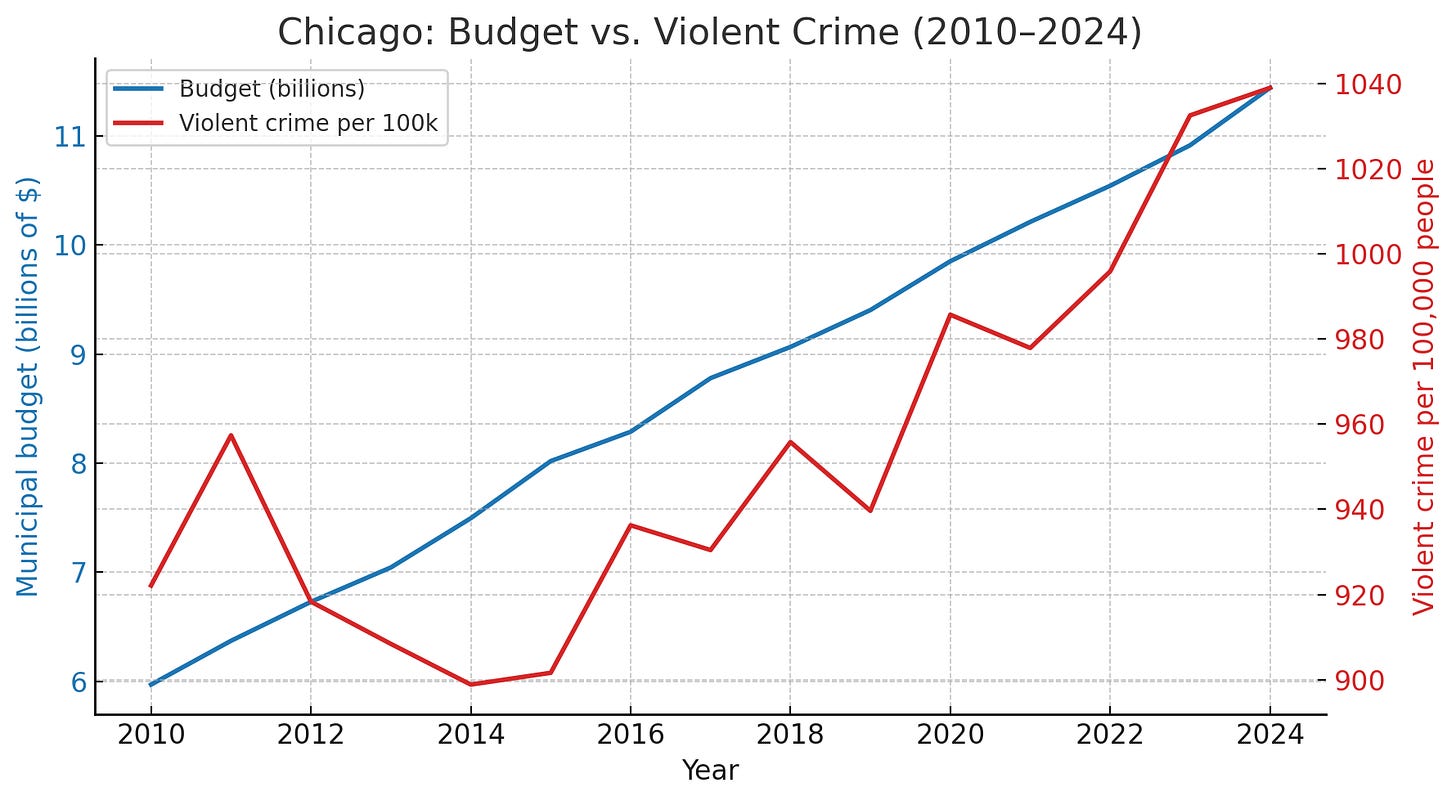

In theory, public spending should rise and fall with population needs. In practice, it rises regardless. Between 2010 and 2024 total municipal budgets in the ten largest U.S. cities increased by an average of 82 percent, while population growth averaged less than 10 percent. Nearly all of that new money went to expanded departments of “equity,” housing subsidies, and social services, not infrastructure. Yet streets, transit, and public safety deteriorated in every one of those cities. The correlation between spending and improvement has all but vanished.

During fiscal 2024, the combined cities of New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago spent over $280 billion, a figure exceeding the entire state budgets of Florida and Texas combined in 2000. Despite this, homicide rates in those three metros stood at 45 percent above their 2014 levels, and unsheltered homelessness more than doubled. A city cannot consume that volume of resources without creating a bureaucracy powerful enough to defend it.

The financial engine now runs on the fuel of government transfer and employment. In Washington, D.C., public‑sector jobs make up 28 percent of all wage earners. In Baltimore, nearly one of every three workers receives a paycheck directly or indirectly from taxpayers. The same pattern appears in Los Angeles and Philadelphia, where city and county payrolls have grown twice as fast as private employment since 2015. When half the local economy exists to administer the other half, political competition becomes meaningless. The bureaucracy votes for itself.

Austin illustrates how rapidly the cycle forms. The city’s projected 2025 budget exceeds $5 billion, a record high. Over half of it funds “public health,” housing, and environmental initiatives. Meanwhile, violent crime has risen 24 percent since 2019, and building permits have fallen by nearly a third. Productive enterprise withers under regulation, leaving the very government that caused the problem to declare itself indispensable.

History confirms the pattern. Detroit’s tax base peaked in 1960 when automobiles led the private economy. By 1985 public employment surpassed manufacturing jobs. Within another decade, property values collapsed and state bailouts began. The city that once built cars came to live on grants.

The economic laws behind this transformation are not complicated. Subsidize something and you get more of it. Tax something and you get less. Cities subsidize dependency and tax productivity. Over time the balance cannot hold. A declining share of producers supports a growing network of administrators and claimants. Prices rise, services decline, and officials call it inequality instead of arithmetic.

Bureaucratic systems seek survival more intensely than citizens seek efficiency. Every budget request, however wasteful, acquires a humanitarian slogan. Jobs depend on problems, so problems are never entirely solved. When voters grow restless, new agencies appear to demonstrate compassion while expanding payrolls.

It is a remarkable trick: to make failure a source of revenue and dependency a political asset. Yet it can only persist because the public has grown accustomed to believing that government outcomes and good intentions are the same.

The Psychology of Crowding

Every mile of pavement added to a city changes more than its skyline. It changes how people think. Crowding does not merely fill space; it rewires behavior. When population density rises, self‑control declines, trust falters, and politics adjust to manage the consequences.

For centuries, philosophers recognized that moral order weakens as numbers grow. Aristotle noted that “in the multitude of men there is always a dearth of virtue.” Modern research confirms what the old philosophers sensed. Density breeds conformity, not originality; anxiety, not cooperation.

In 1962, behavioral scientist John Calhoun created his “behavioral sink,” an enclosed colony where rats were given unlimited food but limited space. The first generations flourished, then the society collapsed into violence and neglect of their young. Calhoun’s experiment, later repeated worldwide, showed that abundance cannot offset the psychological damage of excessive closeness. Crowding magnifies every human weakness and rewards submission over independence.

Human beings respond in much the same way. Decades of evidence show that high‑density living increases stress, aggression, and alienation even when income and safety are held constant. A 2020 University of Michigan meta‑analysis found that social trust drops measurably with each additional 1,000 residents per square mile. The paradox is unmistakable: the greater the number of people around an individual, the more isolated that individual becomes. Crowding does not create community; it replaces community with proximity. What looks like connectedness from the air is estrangement on the ground.

That alienation fuels a hunger for regulation. When daily life feels unstable, people trade liberty for assurances of control. A crowded society demands overseers, the bureaucratic equivalent of a neighborhood watch stretched to infinity. In New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, fear of disorder produces policies that bind everyone, while responsibility for order belongs to no one. By 2024 those three metros together employed over half a million city and county administrators, more than twice the number forty years ago, even as public satisfaction with safety reached record lows.

Crowding also weakens moral accountability. In a small town the potential cost of shame keeps behavior in line. In a city anonymity protects misconduct. People do things in crowds—vandalize, steal, insult—that they would never do among neighbors who know their names. As shame vanishes, statutes multiply. Each new law and compliance office substitutes bureaucracy for conscience. City government becomes a mechanized form of morality.

Children raised in that environment learn obedience, not virtue. Rules come from officials rather than parents, discipline from authority rather than tradition. By adulthood the instinct to look upward for permission is second nature. At the ballot box that same reflex becomes political: voting for power that promises safety feels rational because personal responsibility feels dangerous.

Even definitions of virtue change. In low‑density communities, virtue means taking responsibility. In the city, virtue means avoiding offense. The safest moral position is agreement. Conscience yields to consensus. What begins as civility hardens into conformity, enforced by social pressure and government policy. Compassion turns into performance and bureaucratic subsidy, an effort to display goodness while sending the cost to public accounts.

This is how cities exchange innovation for orthodoxy. Crowding produces dependence because dependence is easier than virtue. The more people packed together, the more they demand management, and the more management they get. Bureaucracy becomes both the cause and the cure of the anxiety it creates.

The real cost of urban life is not traffic or noise. It is psychological compression: a narrowing of the moral and mental space required for freedom. Crowded minds fear risk, fear judgment, and eventually fear liberty itself. They welcome supervision as protection and control as kindness.

Decline of Trust and the Growth of Rules

Cities do not collapse because people stop caring about law. They collapse because they stop trusting one another enough to live without it. Trust is the invisible capital that allows a society to function with limited supervision. When trust disappears, government fills the vacuum.

Sociologist Robert Putnam documented this reality two decades ago in his study of social capital. His research found that as communities become more diverse and more crowded, interpersonal trust falls. The trend has only deepened since his first findings in 2000. Surveys from 2024 show that fewer than one in four residents of large metropolitan areas believe their neighbors would return a lost wallet. In rural counties, nearly three in five believe it would be returned. The contrast explains why cities depend on administrators while small towns rely on expectations.

Low trust changes every interaction. In places where people doubt the honesty of those around them, even small exchanges require official mediation. Government becomes the broker of ordinary life. City codes and compliance offices multiply to handle problems once governed by common sense. A study from the National League of Cities found that between 1980 and 2020 the average American municipality increased its regulatory chapters by nearly 400 percent. Most new provisions deal not with large industry but with personal behavior—noise, waste disposal, building modifications, parking—matters that once could be resolved by a conversation.

Each rule justifies another department, and each department creates new employees who depend on those rules for their livelihoods. What begins as a public safeguard becomes a political ecosystem. The more complex the rules, the more citizens require representatives to interpret and negotiate them. The relationship between voter and government shifts from partnership to dependency.

Policing provides the most visible example. In high‑trust areas, officers are community members. Residents cooperate because the line between citizen and guardian is thin. In cities with low trust, every encounter between police and the public becomes a transaction between strangers. Accusations of misconduct rise, cooperation falls, and oversight bodies expand to monitor the monitors. By 2024 New York City employed more than 90 separate review offices attached to law enforcement functions. The purpose is accountability, yet the outcome is paralysis.

Lawsuits follow policy failure, and settlements consume budgets intended for services. The city that no longer trusts its citizens cannot function without constant supervision. People live side by side but believe the worst of one another. Businesses spend more on compliance than on product improvement. Teachers spend more time documenting conduct than teaching content. Productivity dies in a maze of mutual suspicion.

This dynamic reaches politics itself. When citizens view fellow citizens as threats, they turn to authority as referee. The state becomes the parent of last resort. Every election then rewards those who promise more oversight, more rules, and more protection. The idea of liberty begins to sound dangerous because liberty depends on trust. Freedom without moral confidence looks like chaos, and chaos frightens the dependent mind.

Bureaucracy strengthens as relationships weaken. Each failure of personal character becomes an argument for institutional control. In the long run the relationship becomes irreversible: a population trained to distrust one another cannot easily imagine governing itself.

The Political Conversion Point

Cities do not turn blue overnight. They cross identifiable thresholds where personal independence gives way to collective management and permanent bureaucracy. Those thresholds appear with consistent precision in the census numbers and the voting record that follows.

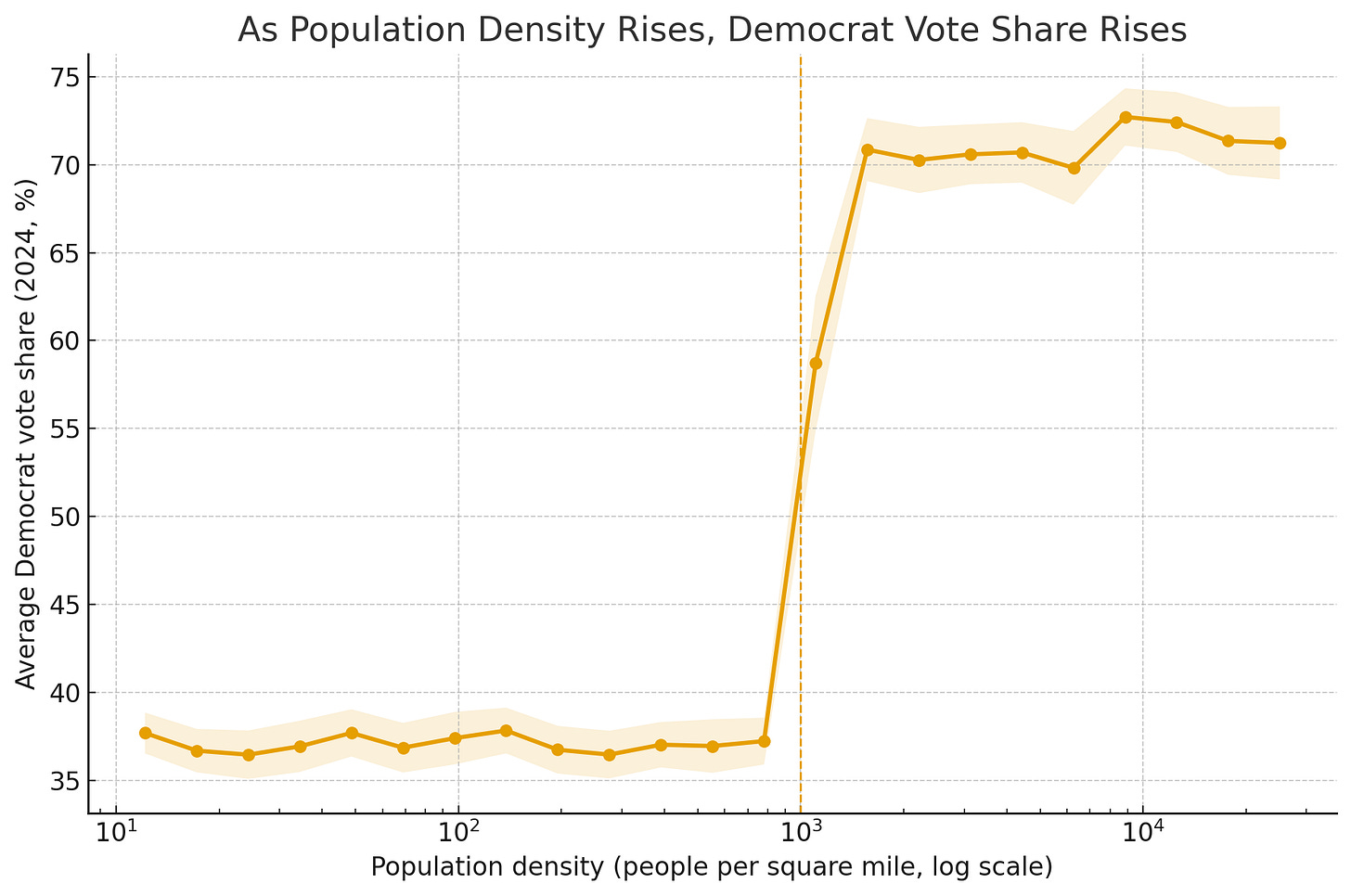

The first variable is density. Across the United States, the strongest predictor of left‑leaning voting is population concentration. Once a community surpasses roughly 1,000 residents per square mile, its political temperament begins to shift. Below that mark, local norms and reputations still regulate conduct. Above it, regulation itself becomes the culture. Counties under that threshold voted Republican by an average margin of twenty‑one points in 2024. Counties above it voted Democrat by nearly the same margin. The dividing line is not ideology, it is environment.

The second threshold involves homeownership. The logic is elementary. Ownership encourages long‑term thinking, while renting fosters short‑term horizons. A homeowner looks at a property as an inheritance. A renter sees it as a temporary station in life. In 2024 the gap in party preference between the two groups reached a historic level: 61 percent of renters identified with or leaned toward the Democrat Party, compared with 38 percent of owners. When homeownership in a growing town slips below 55 percent, local voting patterns shift accordingly within a decade.

Income alone does not reverse the effect. Higher‑income renters still vote for policies that protect tenancy rather than ownership. Their financial security may be strong, yet their emotional stake remains transient. Policies promising “affordability protections” and regulatory housing controls become attractive precisely because they codify dependency as a civic right. Politicians learned long ago that it pays to legislate comfort instead of competence.

The third element is occupational shift. The work of producers gives way to the work of administrators. In 1960 Detroit’s labor force was dominated by manufacturing; today more than half of its public employees work in social services or municipal administration. Service employment now constitutes 86 percent of all urban jobs nationwide, replacing the kind of production that once fostered merit‑based cooperation. As more residents become entangled in government or quasi‑government work, their voting becomes predictably defensive. They protect the hand that signs the paychecks.

Together, these forces—density, transience, and bureaucratic employment—mark what might be called the conversion point. At first, a city’s growth enriches opportunity; then, at a certain size, the same scale reverses incentives. Self‑reliance no longer rewards; negotiation with authority does. Every step above that threshold strengthens the political machinery that depends on permanence of need rather than resolution of problems.

Austin illustrates the transition vividly. In the 1990s it was a business‑friendly hub with a mix of local entrepreneurs and middle‑class homeowners. By 2020 the city’s density reached 3,300 residents per square mile, homeownership dropped below 45 percent, and four of its five largest employers were government agencies or state‑funded universities. Crime rose, regulation multiplied, and the electorate turned permanently blue.

This is not coincidence. It is feedback. A society dominated by renters and administrators cannot sustain the cultural habits required for limited government. It must construct a state big enough to manage both groups. Once that state exists, it perpetuates the very dependency it claims to relieve.

The political conversion point is therefore not ideological but structural. Change the structure and voting patterns follow without debate. The shape of the city shapes the soul of its residents. They accept control as stability and bureaucracy as compassion. By the time they realize how much liberty has been traded, recovery is politically impossible.

Beyond each conversion point lies a city that no longer produces independence, only allegiance. Power grows where dependency grows.

Cultural Reprogramming: The Illusion of Progress

Material decline always hides behind moral language. As cities pass the conversion point, citizens are taught to see government expansion not as failure but as virtue. Dependency is reframed as compassion, and control is presented as progress. The method is not new; only the slogans change.

Every modern city maintains an official vocabulary that replaces moral standards with political terms. Crime becomes “inequity.” Disorder becomes “expression.” Welfare becomes “investment.” By redefining cause and effect, governments convince the public that the very policies producing decay are evidence of social enlightenment. The worse the conditions grow, the nobler the rhetoric must become to disguise them.

Consider the typical urban response to rising homelessness. In 2005 Los Angeles budgeted fewer than $30 million for homeless services. By 2024 the figure exceeded $1.3 billion, yet the number of unsheltered people increased by more than 60 percent. The failure did not discredit the program. It justified larger appropriations and more staff. Officials claimed the rise proved that “root causes” were deeper than expected, requiring further study grants and new departments. The harder the evidence, the gentler the language. Administrators measured success not by results but by sensitivity.

This is cultural reprogramming: redefining virtue as the avoidance of judgment. In a city that operates on ideological sensitivity, reality becomes offensive. A store owner who objects to theft is accused of intolerance. A teacher who enforces standards is criticized for discrimination. A homeowner who wants safety is told to examine privilege. The system trains citizens to question their own moral reflexes while trusting bureaucratic feelings in their place. Civilization is reversed one courtesy at a time.

Data underline the change. In 2024 the top ten U.S. metropolitan areas spent an average of 38 percent of their budgets on departments with words such as “equity,” “community development,” or “social inclusion” in their titles. Yet those same cities recorded homicide rates 44 percent higher than comparable metros two decades earlier. Bureaucracies that publicized compassion failed at protection because compassion required no accountability. Once benevolence becomes office policy, it ceases to perform moral work.

The educational system amplifies the effect. Urban schools now devote classroom hours to emotional training and grievance management while literacy scores decline. National Assessment data show reading proficiency in the twenty largest districts fell from 47 percent in 2013 to 31 percent in 2024. Each drop in performance produced new administrative initiatives promising “social‑emotional learning.” No measurable gain followed, yet the staff count rose and budgets expanded. Lacking results to defend, the system learned to defend intentions instead.

The illusion of progress depends on emotional substitution. Officials present large sums, new offices, and abstract compassion as evidence of motion. Residents observe motion and mistake it for improvement. The symbol becomes the substance. The more meetings held and slogans printed, the more advanced the city pretends to be. Meanwhile, infrastructure rots, public order collapses, and taxpayers fund campaigns congratulating themselves for “doing something.”

Eventually even basic competence becomes controversial. Demanding accountability sounds heartless because accountability implies hierarchy and judgment. The city’s moral vocabulary no longer distinguishes between discipline and cruelty. The bureaucrat becomes the new priest, and the budget the new sacrament. Problems multiply because institutions need them. Each new failure produces another call for solidarity funded by the same taxpayers who must live amid the resulting decay.

In this moral economy, success threatens employment. A solved problem ends a department; an unsolved one expands it. Thus every modern urban policy is designed to show empathy while preserving inefficiency. It is the perfect political machine—an engine that turns breakdown into justification.

The words remain sentimental, but the results are mathematical. The more money directed toward management of misery, the more misery there must be to manage. Compassion, stripped of responsibility, becomes a full‑time occupation.

This is the final illusion of progress: to mistake empathy for effectiveness. When compassion becomes currency, decay becomes industry.

Promises and Outcomes

The rhetoric of compassion always sounds convincing until measured against results. City leaders promise salvation through empathy, spend extraordinary sums of public money, and celebrate intentions long after the evidence of failure becomes unavoidable. A few of the most visible examples show how moral language replaces measurable progress.

Gavin Newsom: “We’ll End Chronic Homelessness.”

In 2018 Governor Newsom pledged to eliminate chronic homelessness in California within ten years. Statewide spending exceeded $25 billion by 2024, yet the homeless population rose from 130,000 to 181,000. San Francisco and Los Angeles broke every previous record for unsheltered residents. Each escalation was labeled “a step in the right direction.”

Bill de Blasio: “We Can Be Both Safe and Fair.”

Elected in 2014, the New York City mayor promised to maintain low crime while reforming policing. The city cut nearly $1 billion from police funding and replaced enforcement with activism. Within five years, murders increased by almost half, car theft doubled, and anxiety replaced safety as the defining mood of urban life.

Lori Lightfoot: “We Are Reducing Violence in Chicago.”

In 2020, Chicago’s mayor announced that new “community investment strategies” were lowering crime. During her tenure, the city recorded over 2,000 homicides, its highest multi‑year total in three decades, along with carjackings unseen since the early 1970s. The programs expanded, the numbers worsened, and rhetoric became the only measurable success.

These episodes are not exceptions. They describe the life cycle of every large city committed to the illusion of progress. Policies fail and budgets expand because admitting cause and effect would dismantle the political machine itself. Each promise manufactures dependency by design: the public becomes client, government becomes caretaker, and results become irrelevant.

Case Studies and Rare Holdouts

The questions of political theory become concrete when you have lived inside the experiment. I grew up ten minutes from San Francisco and spent thirty‑five years in the Bay Area. I have lived the promise and the collapse. For the past decade I have watched Austin, my current home, repeat the same pattern almost line for line. Personal observation, not ideology, anchors what follows.

San Francisco once embodied the entrepreneurial spirit of postwar America. The city offered beauty, tolerance, and possibility. It rewarded discipline. In the 1980s the streets were clean, small businesses thrived, and police still represented public safety rather than political controversy. By the early 2000s the cultural vocabulary had changed. Politics replaced policy; image replaced order.

The evidence of decay was not hidden. Between 2010 and 2024 the city’s budget increased from $6.5 billion to more than $14 billion, yet violent crime rose by 37 percent, property crime by nearly 60 percent, and open drug use became common enough to drive pharmacies and groceries from entire neighborhoods. The number of city employees exceeded 36,000, larger than the total payrolls of many states. The average resident could walk downtown and see that larger government did not yield cleaner streets or safer businesses. San Francisco now spends roughly $100,000 per homeless person per year while adding new homeless every month.

For those of us who remember an earlier city, the change was visceral. Families that once spent evenings at the Wharf or Union Square avoided downtown entirely. Parents warned children not about crime in abstract terms but about collapsed addicts or needles on sidewalks. Schools that used to rank among California’s best fell below state averages despite record funding. Each failure invited additional layers of administration, as if more titles could substitute for discipline.

When I left for Austin more than a decade ago, it felt like a move forward. The Texas capital still carried a mix of grit and ambition. Local government stayed in its lane, policing was respected, and the culture prized personal accountability. Over time that balance shifted. Tech companies brought prosperity but also imported the same politics that had hollowed San Francisco. The population exploded from 800,000 to nearly 1.2 million. Housing codes multiplied. The city created new offices for “equity,” “sustainability,” and “social innovation.” Violent crime rose by 24 percent between 2019 and 2024, and the city’s budget more than doubled. Homeless encampments appeared beneath overpasses that had been spotless a decade earlier.

The language in council meetings became identical to the meetings I used to watch in San Francisco: the same insistence that compassion could replace enforcement, the same unwillingness to admit that unearned empathy destroys order. When police withdrawal led to predictable chaos, officials cited “systemic” forces and hired more consultants. Every response ensured new dependence on government management. Austin under construction began to look like California in slow motion.

What changed in both cities was not ideology but incentives. When order collapses, power flows to whoever offers coordination. For bureaucrats, disorder is job security. For citizens who fear confrontation, bureaucracy feels like moral safety. Both sides benefit from dependence at the cost of liberty.

Other cities illustrate the same arithmetic with different accents. Chicago spends over $16 billion a year on municipal operations and records less trust in police and government than any major American city. Los Angeles spends nearly $2 billion annually combating homelessness yet counts more homeless people than any metropolis in the Western Hemisphere. Each is a variation on one formula: subsidize failure, redefine it as progress, and promise more spending to show concern.

Yet some places still resist the pull. Fort Worth remains largely self‑governing by instinct. It protects its working culture, enforces standards without apology, and keeps its bureaucracy human‑sized. Oklahoma City sustains a production economy that limits the ideological importation seen elsewhere. Jacksonville and parts of Miami counter the trend with high homeownership and strong law enforcement. None are perfect, yet each demonstrates that the decay of cities is not inevitable. Where order is defended and family structure remains intact, freedom still yields stability.

To watch Austin repeat San Francisco’s trajectory is painful because the outcome is predictable. Decay travels faster than construction. Bureaucracies never unbuild what they build. Culture, once surrendered, seldom returns within a generation. San Francisco shows the destination; Austin shows the journey. Both prove the same rule of civic gravity: where dependency takes root, liberty becomes ornamental.

Every expanding government begins as caretaker and ends as owner. The places that remember that distinction remain free.

Misery Loves Company

The same pattern that hollowed San Francisco and is reshaping Austin now defines the modern metropolis. The formula is simple: grow dense enough, regulate enough, and indoctrinate enough, and a community that once produced independence will begin producing excuses instead. What changes first is the culture; what follows is everything else.

Misery in cities is neither accidental nor evenly distributed. It is cultivated. The bureaucratic state converts dysfunction into proof of its importance. Every visible failure strengthens the rationale for larger budgets, more social programs, and greater supervision. Citizens who endure those failures are told they are courageous for “staying and caring.” Protest becomes therapy. Decline becomes identity. When everyone suffers together, no one feels responsible.

That emotional unity is the secret of the blue city. The politics of grievance need chronic grievance to survive. A healthy population would require freedom and self‑discipline, which leave little room for dependency. But dependent people provide guaranteed votes, and guaranteed votes provide guaranteed power. As long as urban misery is shared widely enough, its administrators remain secure.

The mechanism works as psychological comfort. A resident of a failing city rarely compares his condition to life outside the metro; he compares it to the person next door who is faring just as poorly. Relative equality inside decline offers a strange reassurance. People submit to incompetence so long as it is universal. This is why calls for “collective solutions” always thrive precisely where nothing is being solved. When outcomes are uniformly bad, the public learns to equate pity with fairness and stagnation with stability.

The city becomes a moral commune held together by shared decline. Churches empty, civic clubs die, and politics becomes the new faith. Residents talk about justice rather than virtue because justice can be delegated to institutions while virtue cannot. Compassion turns into spectacle: marches, slogans, and hashtags that exhaust emotion but demand no standards. The crowd finds bliss in collective despair, mistaking it for solidarity. Thus, misery does more than love company—it requires it.

The end stage appears the same everywhere. Officials quote empathy while issuing curfews. Taxpayers fund compassion they no longer feel. Voters insist they want change but fear responsibility more than chaos. Cities reach a point where order itself seems oppressive because order begins inside the individual. That is the one form of reform bureaucracy cannot administer.

A few places resist because they still remember the value of loneliness. Freedom sometimes resembles solitude. It demands character and courage—the opposite of the comfort offered by the collective. Communities that protect family, faith, and ownership preserve the emotional distance required for moral independence. They retain the ability to say no both to chaos and to control. Those will be the cities that survive.

Every empire, ancient or modern, has discovered the same civic arithmetic. The greater the crowding, the greater the fear; the greater the fear, the greater the call for management; and the greater the management, the more complete the dependency. Eventually the people mistake oversight for civilization and equality of misery for justice. That is where America’s great cities now stand.

They call it progress. They call it compassion. They call it equity. But it is dependency in disguise, and it spreads exactly the way fear spreads—quietly, inevitably, and always downward. Misery seeks company, and power seeks both. Power grows where dependency grows.

If this helped clarify why density turns into dependency, help me keep doing work like this.

Arnell’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. I don’t run ads. I don’t hide my work behind paywalls. Everything I write is for everyone, especially the people no one else will speak for.

If you value this work, you can help keep it going:

Become a Paid Subscriber: https://mrchr.is/help

Join The Resistance Core (Founding Member): https://mrchr.is/resist

Buy Me a Coffee: https://mrchr.is/give

Sharing and restacking also helps more than you know.

Democrats have learned the art of appealing to people's natural inclination towards envy, greed, and grievance. It's a powerful tool to generate votes.

“The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money.”

― Alexis de Tocqueville

“Democracy extends the sphere of individual freedom, socialism restricts it. Democracy attaches all possible value to each man; socialism makes each man a mere agent, a mere number. Democracy and socialism have nothing in common but one word: equality. But notice the difference: while democracy seeks equality in liberty, socialism seeks equality in restraint and servitude.”

― Alexis de Tocqueville

Great post. As it appears that November food stamps won’t drop the people in my neighborhood are freaking out. Someone posted on the neighborhood website group that they would give away food and wrote, “If the government won’t feed my neighbors, I will!” Isn’t it funny that they are outraged that the government isn’t doing what individuals, families and communities should be doing, and so now they decide to help their neighbors? I wonder how many of the people on SNAP really need it. Will we see an epidemic of weight loss as they starve ? Doubt it.