The Elusiveness of Black Self-Reflection: Everything Disproportionately Impacts Black People Except Accountability

Why the numbers never change when the excuses never stop.

When Black Americans argue that crime laws disproportionately affect Black and Brown people, has it ever occurred to them that committing fewer crimes might be the simplest solution?

The Mirror No One Wants to Face

When Black Americans claim that crime laws disproportionately impact Black and Brown communities, the question that is never asked, but desperately needs to be, is whether the solution lies not in changing the laws, but in changing the behavior.

The very premise that crime enforcement is unfair because of who it affects reveals something few are willing to acknowledge. It assumes that the underlying behavior is fixed, unchangeable, and perhaps even justified. That argument would be quickly dismissed in any other context. No one argues that the law against embezzlement is unfair to the wealthy solely because most embezzlers are accountants. But when it comes to violent crime, theft, and drug-related offenses, racial disparity becomes a shield used to avoid uncomfortable truths.

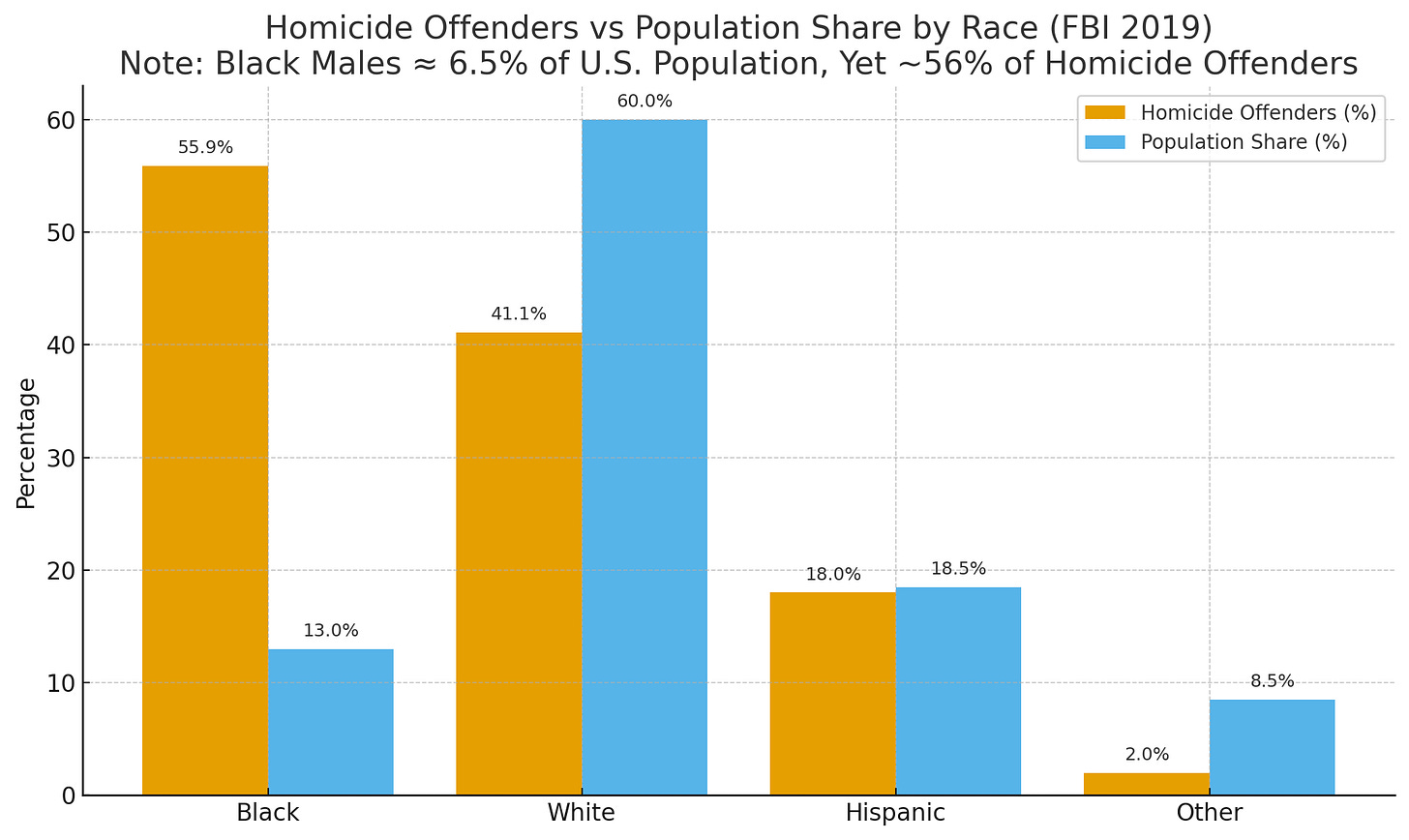

The facts are not hard to find. According to FBI data, Black Americans make up roughly 13 percent of the U.S. population. Black males, specifically, are around 6.5 percent. Yet this small segment is responsible for approximately half of the country’s murders. In 2019, for example, the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting showed that 55.9 percent of known homicide offenders were Black. That isn’t a narrative. That’s arithmetic.

These numbers are not explained by poverty alone. Poor White Americans in places like Appalachia live in conditions every bit as bleak as their inner-city counterparts. What they do not produce in nearly the same numbers are carjackings, flash mob robberies, or drive-by shootings. If poverty were the engine, one would expect crime to follow income uniformly, regardless of race. It doesn’t.

And yet, whenever police enforcement rises in cities like Washington, D.C., Chicago, or Philadelphia in response to actual crime spikes, the pushback is immediate. Leaders and activists insist these efforts unfairly “target” Black neighborhoods, as if the zip code and not the shooting rate determined police presence. The underlying logic seems to be that crime enforcement should reflect demographic quotas, rather than criminal behavior. By that reasoning, police should arrest more elderly Asian women to avoid racial disparities, even if they are not the ones committing the crimes.

What this line of thinking reveals is a near-total absence of self-reflection. Not only is the behavior never examined, but it is often excused, rationalized, or even glorified. Entire genres of music romanticize criminal life, and whole political movements treat criminals as misunderstood revolutionaries rather than predators. When George Floyd died under the knee of a Minneapolis officer, his criminal history was wiped clean overnight. When Jacob Blake was shot while resisting arrest and reaching for a weapon, it was treated as a civil rights violation rather than a police encounter involving a wanted man.

To even suggest that some of the problems in these communities are self-inflicted is treated as an act of betrayal. But if a community is suffering, and suffering from things that are within its control, it is not compassion to ignore that. It is cowardice.

If the rules of civilized society are to mean anything, they must apply equally. That means behavior has consequences. And when one group consistently generates a disproportionate amount of criminal behavior, the resulting consequences will also be disproportionate. That is not injustice. That is math.

The refusal to confront this is not just intellectually dishonest. It is dangerous. Because the more we twist ourselves into knots, avoiding the truth, the worse the problem becomes. And when the truth finally becomes too big to ignore, it may be too late to fix.

The Rhetorical Formula: ‘Disproportionate Impact’ as a Cop-Out

The phrase “disproportionately impacts Black and Brown people” has become a kind of political Swiss Army knife. It appears in speeches about crime, in debates over education, in arguments about health care, housing, and even climate change. The formula is simple and effective. If the outcome is unequal, declare it unjust. If a policy produces different results across racial groups, blame the policy rather than examine the behavior or choices that led to the disparity.

Consider policing. When crime rates are highest in predominantly Black neighborhoods, police patrols naturally concentrate in those areas. The result is more arrests. Activists then argue that policing disproportionately impacts Black people, as if police are targeting neighborhoods randomly. In fact, they are following the crime. Yet the language flips cause and effect. The high crime rate does not explain the high arrest rate. Instead, the high arrest rate is presented as evidence of racism.

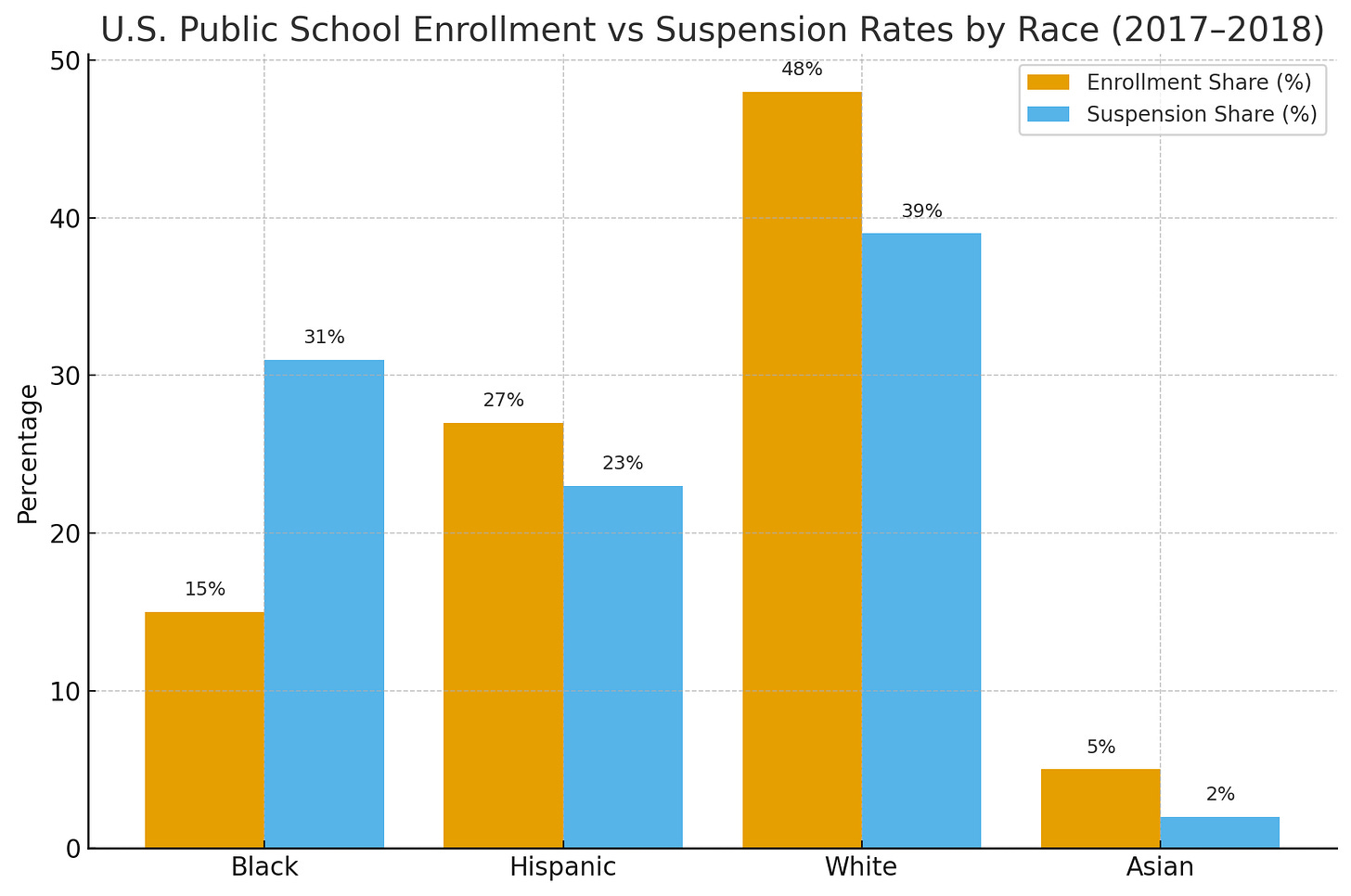

The same formula plays out in education. Black students are suspended at higher rates than White or Asian students. The assumption is that teachers and administrators are biased. What is seldom asked is whether misbehavior occurs at different rates or whether classroom disruptions are more frequent in some schools than others. When researchers in California examined school discipline disparities, they found that schools with identical policies still produced very different outcomes depending on the student body. In other words, the disparity was not in the rules but in the conduct. Yet the official narrative remains that suspensions disproportionately impact Black students, as though behavior had nothing to do with it.

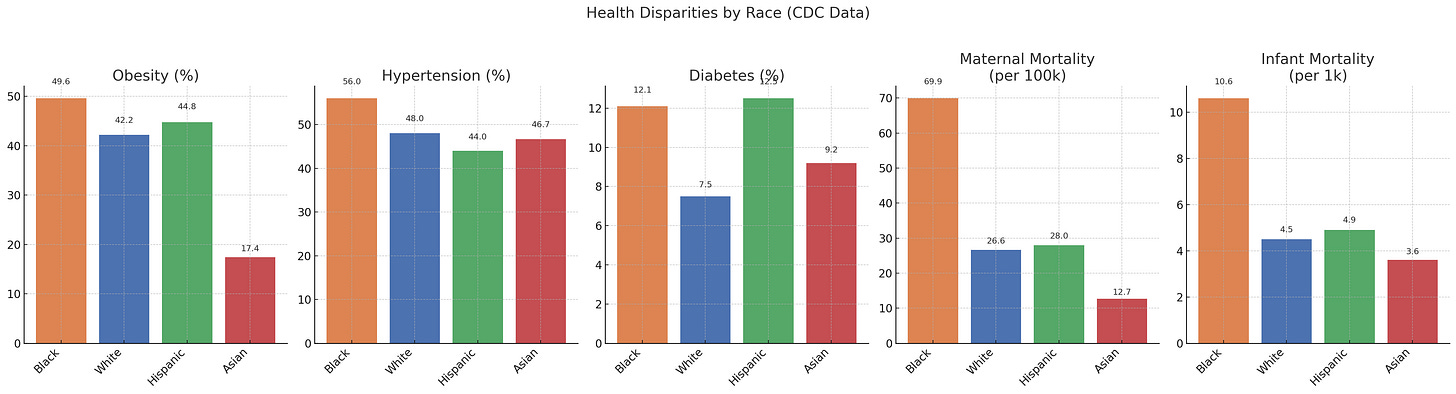

Health care offers another example. During the COVID-19 pandemic, headlines regularly proclaimed that the virus disproportionately affected Black and Brown communities. The implicit message was that the health system had failed those groups. What went unspoken was that pre-existing conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, conditions more common in Black populations, were major predictors of severe outcomes. Lifestyle factors like diet and exercise were largely absent from the discussion. Instead, the formula converted health disparities into accusations of systemic bias.

Even housing and economic trends are folded into this narrative. When property values rise in urban neighborhoods, the term “gentrification” is invoked to suggest that development disproportionately harms Black residents. Yet the reason values rise is that people want safer streets, better schools, and livable communities. Those improvements are not resented in White suburbs. They are celebrated. But in the language of disproportionate impact, the very presence of improvement becomes another grievance.

Politicians find this formula irresistible because it requires no solutions, only slogans. To say that outcomes reflect differences in behavior would be politically dangerous. To say they reflect injustice is politically rewarding. By repeating the phrase “disproportionately impacts Black and Brown people,” leaders can signal compassion without addressing the underlying causes. It costs them nothing, yet earns them applause. Meanwhile, the problems remain unsolved, and the communities most affected are left with the same cycle of grievance and decline.

This rhetorical trick works only because people allow it to work. Few dare to question whether the disparities might reflect fundamental differences in choices, habits, or cultural patterns. Fewer still ask whether constantly framing outcomes as oppression undermines the very possibility of improvement. To accept the formula is to assume that the solution to every problem lies outside the community, never within it. And that is precisely why it is so popular, and so destructive.

Crime: Where the Truth Screams Loudest

If there is any subject where the phrase “disproportionate impact” unravels most completely, it is crime. The numbers do not whisper; they shout. Black Americans make up about 13 percent of the U.S. population, and Black males about 6.5 percent, yet they account for more than half of the nation’s murders. This is not a one-time fluke. The disparity has been remarkably consistent for decades, across different economic cycles, in Democrat cities and Republican states alike. It is one of the most stable and sobering features of American crime statistics.

The FBI’s last comprehensive national dataset, published in 2019 before the agency changed its reporting system, showed that 55.9 percent of known homicide offenders were Black. Since then, city-level data have filled the gap, and they confirm the same reality. In Washington, D.C., more than 90 percent of homicide suspects in 2023 were Black. In Chicago, 80 percent of homicide victims in 2021 were Black, with offenders overwhelmingly Black as well. In Philadelphia in 2022, more than 80 percent of both victims and offenders were Black. These are not isolated cases. They are the modern continuation of a statistical pattern that has been visible for generations.

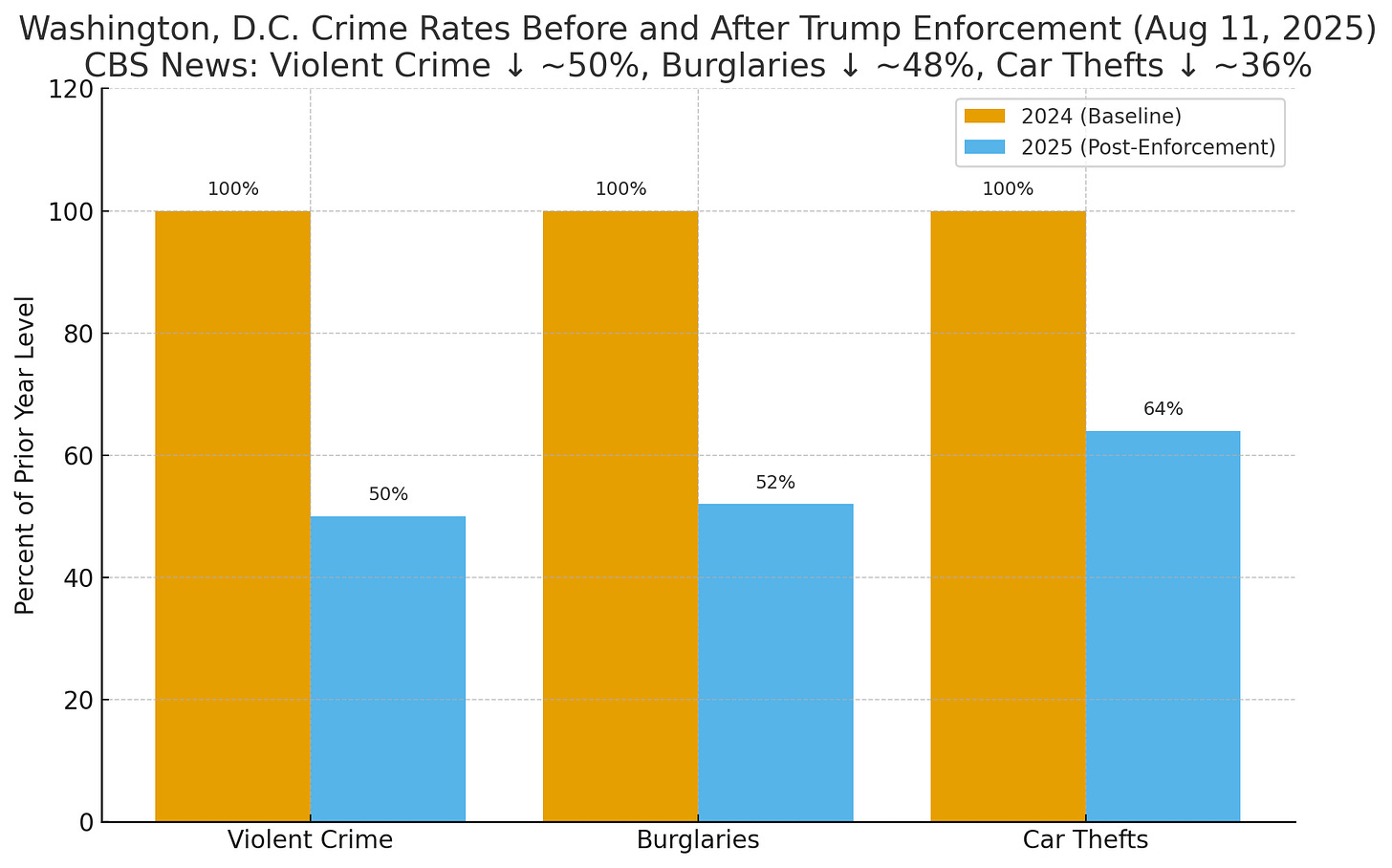

Washington also provides a recent example of what happens when laws are actually enforced. On August 11, 2025, President Trump invoked Section 740 of the D.C. Home Rule Act and declared a public safety emergency, deploying about 800 National Guard troops and federal agents to assist with policing. Within weeks, the results were visible. CBS News reported that violent crime in D.C. fell by nearly 50 percent compared to the same period the year before. Burglaries dropped 48 percent, car thefts 36 percent. These numbers will need more time to settle, and some of the decline may reflect normal seasonal shifts, but the sharp drop following stricter enforcement shows something that should be obvious: when crime is confronted, it falls. That lesson will be ignored by those who prefer slogans to solutions, but it is no less accurate for being uncomfortable.

The response from political leaders and activists, however, has been to blame the system. If police patrol heavily in Black neighborhoods, the claim is that the communities are being unfairly targeted. If incarceration rates are high, the claim is that sentencing practices are biased. But the deployment of police is not based on census quotas. It is based on the locations of the shootings. In D.C., patrol cars are east of the Anacostia River because that is where the murders are. In Chicago, detectives are not sent to Lincoln Park in the same numbers as they are to Englewood, for the simple reason that the violence is not evenly spread across the city. To call this “over-policing” is to misunderstand the basic arithmetic of crime.

The tragedy is not only that these realities are denied, but that the denial comes at the expense of the very people most victimized by the crime. The majority of the victims in these cities are Black, killed not by police or by White vigilantes but by other Blacks. Yet when the subject arises, the loudest voices are focused on the treatment of offenders, not on the safety of victims. The narrative gives more sympathy to the man with the rap sheet than to the mother who loses her child in a drive-by.

To say that crime enforcement disproportionately impacts Black people is statistically accurate. But the cause is not the law. It is behavior. When six percent of the population generates half the murders, the result will inevitably be disproportionate enforcement. That is not a sign of racial injustice. That is the predictable result of actions meeting consequences. Pretending otherwise may win applause in political rallies, but it leaves neighborhoods trapped in violence.

The numbers are clear, the consistency undeniable, and the consequences devastating. Yet the mirror remains avoided, and the deflection continues. The louder the denial, the longer the suffering.

Education: Where Discipline Is Racist and Expectations Are Oppression

The same rhetorical formula that is used to excuse crime is also applied in education. Whenever Black students are suspended or expelled at higher rates than their peers, the conclusion is immediate: the system must be racist. Rarely is it asked whether misbehavior occurs at different rates or whether classroom disruptions are more frequent in some schools than others. The focus remains on the disparity in punishment, not the disparity in behavior.

The Department of Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection shows this pattern clearly. In the 2017–2018 school year, which remains one of the most complete national datasets, Black students represented about 15 percent of public school enrollment but accounted for 31 percent of all suspensions. Hispanic students, 27 percent of enrollment, accounted for 23 percent of suspensions. White students, who comprise 48 percent of enrollment, accounted for only 39 percent of suspensions. Critics seize on these gaps as proof of bias. What they do not explain is why teachers across the country, from rural to urban schools, would conspire to punish Black students more harshly while somehow treating Asian students more leniently.

Local numbers reinforce the point. In New York City, the nation’s most extensive school system, Black students made up just under 24 percent of enrollment in 2019–2020 but nearly half of all suspensions. In Los Angeles Unified, Black students represented about 8 percent of enrollment in 2020–2021 but accounted for more than 20 percent of suspensions. The disparities exist coast to coast, in districts run by liberals and conservatives alike. The one thing they all have in common is not teacher prejudice, but student behavior.

The refusal to admit this has produced predictable consequences. Schools are under pressure to reduce suspensions in the name of equity, regardless of how students actually behave. The Obama administration pushed “discipline reform” guidelines in 2014 that discouraged suspensions, arguing that they contributed to the so-called school-to-prison pipeline. Districts that adopted these reforms saw classroom order collapse. Teachers reported being unable to control disruptive students, and in some cases, physical assaults on staff increased. Minneapolis, Philadelphia, and St. Paul are just a few examples where discipline reforms led to chaos, followed by demands for even more reform when outcomes did not improve.

The cost of these policies is borne not by politicians or activists, but by students who come to school to learn. A classroom disrupted by one or two habitual troublemakers is no longer a place where education can happen. Lowering the bar for discipline does not raise achievement. It drags everyone down. The victims are often other Black students who lose their chance to focus because administrators refuse to confront the misbehavior of their peers.

Yet the phrase “disproportionately impacts Black and Brown students” continues to dominate the conversation. It allows schools to shift responsibility away from behavior and onto the system. The incentive is not to improve student conduct, but to massage the numbers so that disparities appear smaller on paper. Meanwhile, the achievement gap persists, and the very students who need the most structure and discipline are left with the least.

This is not compassion. It is abandonment disguised as fairness. If students learn that they will not face consequences for disrupting class, they carry that lesson with them long after graduation. The refusal to enforce standards in school prepares them for failure in work, in society, and often in the criminal justice system later on. A community that excuses misbehavior in children should not be surprised when those same children grow into adults who test the limits of the law.

Health, Housing, and Economics: Turning Every Outcome into Oppression

The “disproportionate impact” refrain is not limited to crime and education. It is applied across nearly every measure of life outcomes, turning any gap into a grievance. Health statistics, housing trends, and economic disparities are all folded into the narrative that Black and Brown people are victims of systems, never of choices.

Health care provides one of the clearest examples. During the COVID-19 pandemic, headlines regularly proclaimed that the virus disproportionately affected Black and Brown communities. That was true in terms of outcomes. The CDC reported that Black Americans were nearly twice as likely to be hospitalized and more than twice as likely to die from COVID as White Americans during the first year of the pandemic. Yet the reasons were seldom explored honestly. Pre-existing conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, conditions more prevalent in Black population, were major predictors of severe illness. According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, nearly 50 percent of Black women are obese, compared to about 38 percent of White women. Black adults also face higher rates of hypertension, with prevalence estimates around 56 percent, compared to about 48 percent for White adults. These differences matter. But instead of examining the role of lifestyle, diet, and exercise, the disparities were attributed almost entirely to systemic racism in health care delivery.

Housing follows the same pattern. When property values rise in historically Black neighborhoods, the term “gentrification” is invoked. The story is that new development displaces long-time residents, pushing them out through higher rents and taxes. What is left unsaid is that the improvements, lower crime, better schools, renovated housing stock, are the very things residents often say they want. Rising property values are not condemned in White suburbs. They are celebrated as a sign of stability and prosperity. Yet in cities like Washington, D.C. or Brooklyn, when outsiders move into Black neighborhoods and property values rise, the result is treated as an injustice. The problem, we are told, is not decades of crime and blight, but the fact that neighborhoods improved when someone else moved in.

Economic statistics are perhaps the most frequently cited evidence of systemic oppression. The racial wealth gap is regularly described as proof that the system is stacked against Black Americans. Federal Reserve data show that the median wealth of White families is about six to seven times that of Black families. But wealth is not generated in a vacuum. Saving, investing, rates of marriage, and the transmission of assets from one generation to the next all contribute to wealth accumulation. Groups such as Asian Americans, who also faced discrimination historically, now surpass Whites in median household income, largely because of higher educational attainment and higher rates of marriage. The existence of such disparities undermines the claim that racism alone explains wealth gaps, but the narrative remains fixed: if Black outcomes lag, the system must be at fault.

What all of these examples share is the same avoidance of self-reflection. If health outcomes are poor, the blame is on the hospital. If housing improves, the blame is on developers. If wealth gaps persist, the blame is on capitalism. At no point does the conversation turn inward, asking what choices might be contributing to these differences. The narrative is easier when accountability lies somewhere else. It allows grievances to accumulate without requiring change. And it ensures that the same problems will persist, year after year, because no one is willing to name the behaviors that sustain them.

The Role of Politicians: Feeding the Delusion

If there is one group that benefits most from the refusal of self-reflection, it is politicians. By repeating the language of “disproportionate impact,” they can signal compassion without confronting behavior. It is a cheap form of empathy that costs them nothing and buys both votes and applause. To acknowledge cultural breakdown, fatherless homes, or self-destructive choices would be political suicide. To declare the system unjust is politically safe.

The examples are endless. When New York City debated changes to school discipline, Mayor Bill de Blasio argued that suspensions “disproportionately affect Black and Brown children” and pledged to reduce them. The assumption was that the punishments were unfair, not that the behavior was unequal. Teachers in the city quietly reported that classrooms became more complicated to manage, but the political benefit of appearing compassionate outweighed the costs borne by students trying to learn.

During the pandemic, President Joe Biden declared that COVID-19 was “taking a devastating toll on Black and Brown communities” and promised targeted equity initiatives. The disparities were real, but the causes, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, were never mentioned. To do so would have shifted responsibility from the system to individual choices. Instead, the narrative of disproportionate impact was repeated, and the policy solutions revolved around more funding and more bureaucracy.

Even in criminal justice, the same rhetoric dominates. Kamala Harris, as a senator, frequently pointed to incarceration rates as evidence that the system “targets” Black and Brown men. The fact that crime rates themselves are not evenly distributed was absent from her speeches. The same pattern has been echoed by local officials in cities like Philadelphia and Chicago, where leaders condemn the justice system as racist while their neighborhoods record some of the highest murder rates in the country.

The political payoff is obvious. By placing blame outside the community, leaders protect themselves from accountability. They do not have to deliver lower crime, better schools, or healthier citizens. They only have to deliver outrage. In fact, the worse the outcomes, the greater their political leverage, because disparities provide the fuel for their campaigns. As long as voters believe that every negative statistic is evidence of oppression, politicians can present themselves as defenders, even while nothing improves.

Thomas Sowell once observed that there are people “who have a vested interest in poverty.” The same can be said of grievance. Entire careers are built on the premise that Black America is permanently under siege by external forces. The incentive structure rewards those who amplify the perception of injustice and punishes those who suggest that responsibility might lie closer to home. Politicians are not blind to the numbers. They know the crime rates, the test scores, and the health statistics as well as anyone. They simply know that telling the truth about them would end their careers.

This is why the phrase “disproportionately impacts Black and Brown people” is repeated so often. It allows leaders to sound empathetic while doing nothing to address the cause. It sustains the cycle of grievance politics, where problems are valuable not to solve, but to keep alive. And it ensures that accountability remains as elusive in politics as it is in the communities themselves.

What Gets Protected by Avoiding Reflection

The avoidance of self-reflection is not harmless. It shields some of the most destructive patterns in Black America from scrutiny. By framing every disparity as oppression, the narrative protects behaviors and institutions that would collapse under honest examination.

The first is the breakdown of the family. In 1965, Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s report on the Black family warned that rising rates of illegitimacy threatened the stability of Black communities. At the time, about 25 percent of Black children were born outside of marriage. That figure was already far higher than for Whites. Today, it is over 70 percent. Among Hispanic families, the number is about 40 percent, and among Whites, about 30 percent. These are national figures from the CDC. The pattern matters because children raised without fathers are far more likely to struggle in school, commit crimes, and end up incarcerated. The correlation between fatherlessness and negative outcomes is one of the strongest in social science, yet politicians treat the subject as taboo. To point it out is to be accused of blaming the victim. To ignore it is to pretend the numbers do not exist.

The second is the culture that glorifies lawlessness. Entire industries profit from the romanticizing of gang life, drug dealing, and violence. Rap lyrics celebrate killing rivals, degrading women, and defying the police. These messages are not fringe. They are mainstream, backed by major record labels and consumed by millions. Young men grow up believing that respect comes through intimidation, not achievement. When their behavior leads to arrest, the explanation is not that they followed a destructive script but that the system disproportionately targets them. Culture is never examined, because to criticize it is to risk accusations of racism, even when the critique comes from within the Black community itself.

The third is the erosion of educational standards. When schools reduce suspensions to satisfy equity goals, they protect disruptive students at the expense of those who want to learn. The rhetoric of disproportionate impact shields misbehavior by treating punishment as the problem. The same logic applies to standardized testing. When Black students underperform, the tests themselves are called racist. That deflection protects a failing system and the people who run it. The students, especially those who are disciplined and capable, are the ones who lose.

What is most striking is that these patterns are not universal to minority groups. Asian Americans, for example, faced open discrimination well into the twentieth century. Japanese Americans were interned during World War II. Yet today, Asian households have higher median incomes than White households, largely because of higher educational attainment and lower rates of out-of-wedlock births. Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe arrived poor and unwelcome, yet within a few generations had built institutions, businesses, and wealth. The difference is not that discrimination skipped these groups, but that their cultures did not encourage self-destruction or excuse it when it occurred.

By refusing to look inward, Black leaders and activists protect the very forces that are undermining their own communities. Fatherless homes remain unchallenged. Violent subcultures are defended as authentic expression. Failing schools are excused instead of reformed. The victims of these policies are not the politicians or the activists. They are the children who grow up without stability, the students whose classrooms are hijacked by chaos, and the residents trapped in neighborhoods where crime is excused rather than confronted.

Shelby Steele once wrote that the tragedy of the civil rights era was that it shifted the locus of responsibility from within to without. Once the battle against legalized segregation was won, the most challenging task left was self-governance. That was the task many refused to face. The deflection of blame may serve political interests and cultural pride, but it leaves communities locked in cycles of dysfunction that no government program can break.

What True Self-Reflection Would Look Like

What would happen if the conversation shifted from deflection to reflection? If, instead of asking how systems could bend to accommodate behavior, the question became how behavior could change to fit the demands of civilization? The picture would look very different from what we see today.

Start with the family. The data on fatherhood are clear. Children raised in two-parent households, across all races, are less likely to drop out of school, less likely to commit crimes, and less likely to end up poor. A 2017 study from the U.S. Census Bureau found that children living with two married parents had a poverty rate of 7.5 percent, compared with 45 percent for those in single-mother households. Incarceration rates show a similar pattern. Young men raised without fathers are several times more likely to end up behind bars. If Black leaders acknowledged this and placed family stability at the center of reform, the results over time would be transformative.

Education is another area where reflection could replace excuse-making. The lesson from immigrant groups is instructive. Asian Americans, despite language barriers and a history of discrimination, have outperformed other groups in educational attainment. According to Pew Research, about 54 percent of Asian American adults hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 32 percent of Whites and 21 percent of Blacks. This did not happen because the system bent to accommodate them. It happened because cultural expectations demanded it. Homework, discipline, and respect for teachers were nonnegotiable. If those same expectations took root in Black communities, disparities in suspension and test scores would begin to shrink, not because standards were lowered, but because behavior changed.

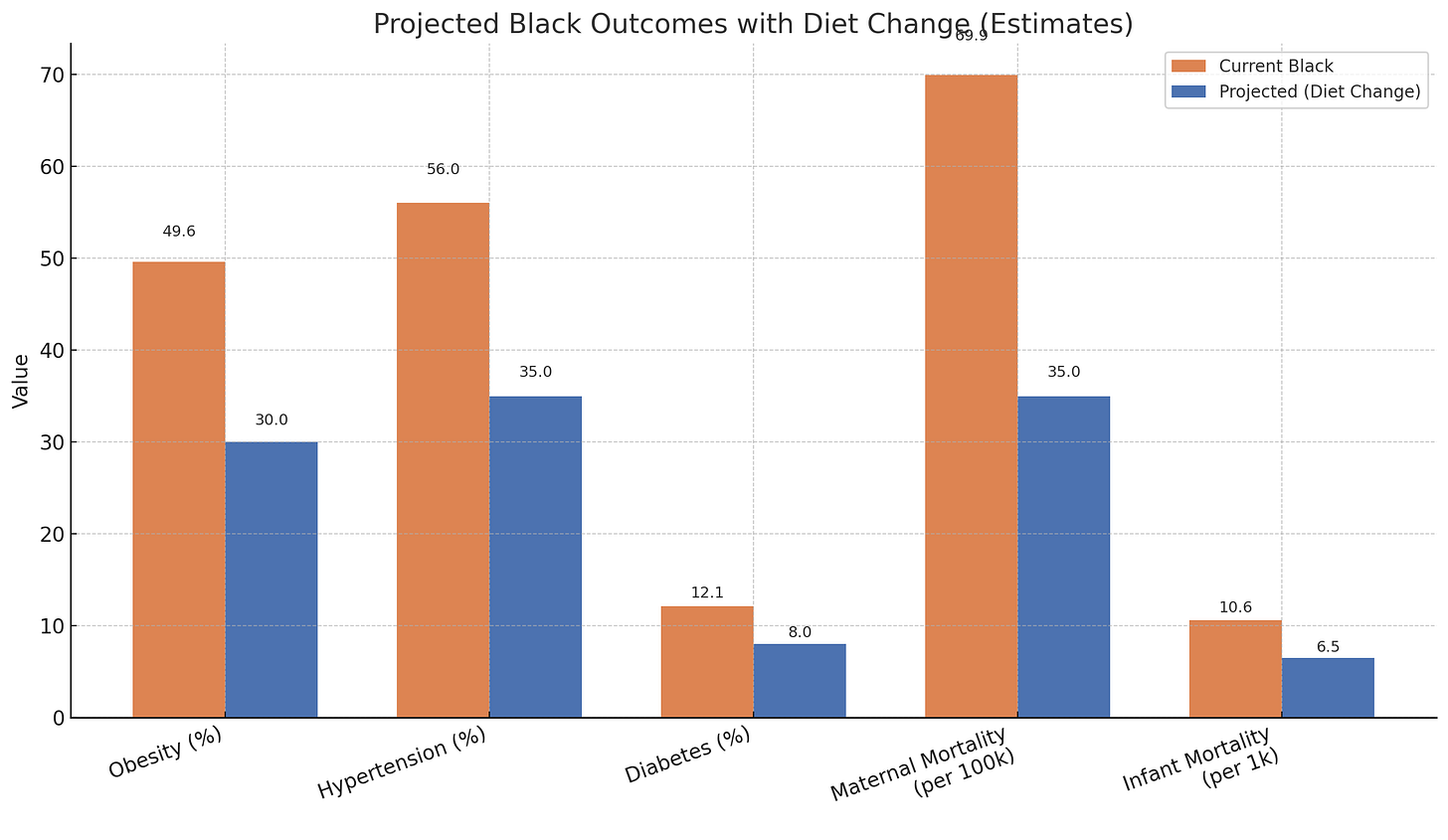

Even health outcomes could improve through self-reflection. Obesity, hypertension, and diabetes are not distributed by race alone, but by lifestyle. In the mid-twentieth century, Japanese immigrants to the United States had rates of cardiovascular disease that mirrored those of their counterparts in Japan. Within a generation, after adopting Western diets heavy in processed foods, their rates of heart disease rose to American levels. Culture, not genetics, was the driver. The same principle applies to the disparities in Black health today. A culture that valued discipline in diet and exercise as much as it does in sports would not need government task forces to close health gaps.

History shows that groups who embraced self-reflection, even in the face of real oppression, eventually moved upward. Jewish immigrants in the early 1900s lived in crowded tenements, often working in sweatshops for meager pay. They faced quotas in universities and open hostility in neighborhoods. Yet by emphasizing family, education, and entrepreneurship, they rose within a few generations. The barriers they faced were real, but their response was not to demand that society lower its expectations. It was to meet those expectations and then surpass them.

If Black America were to adopt a similar posture today, the narrative of disproportionate impact would begin to fade. Arrest rates would fall because crime would fall. Suspension rates would drop because classrooms would be orderly. Health outcomes would improve because lifestyle choices would improve. Economic gaps would narrow because families would save and invest rather than consume and depend. None of this requires new government programs. It requires cultural change, reinforced by personal responsibility.

Self-reflection is not a denial of history. It is a recognition that history cannot be undone. The real question is what to do now, with the choices available in the present. Groups that have asked that question honestly have risen, no matter how deep the disadvantages they began with. Groups that avoid it remain trapped. The future of Black America depends on whether it is willing to ask the question that has been avoided for too long.

Accountability Is Not White Supremacy

The phrase “disproportionately impacts Black and Brown people” has become a reflex in American politics and culture. It is repeated whenever outcomes are unequal, as if inequality itself were proof of injustice. Yet unequal outcomes do not always mean unequal treatment. They often reflect unequal behavior, unequal effort, and unequal choices. To deny that is not compassion. It is self-deception.

Accountability is not a form of oppression. It is the foundation of any functioning society. A community that insists on shielding itself from accountability cannot expect safety, prosperity, or respect. The hard truth is that the disparities in crime, education, health, and wealth are not going to disappear through rhetoric, subsidies, or lowered standards. They will disappear only when behavior changes.

Politicians may gain from keeping the grievance alive. Activists may build careers from repeating the rhetoric of disproportionate impact. But ordinary people pay the price. The victims of crime, the students in chaotic classrooms, the patients suffering from preventable illnesses, all of them lose when accountability is treated as taboo. What is preserved in the name of equity is, in practice, the very dysfunction that holds communities back.

Other groups have faced discrimination, poverty, and hostility. Jews in the early twentieth century, Japanese immigrants in the aftermath of World War II, and Asian Americans more broadly have all experienced barriers. Yet they rose by meeting standards, not demanding that standards be lowered. They succeeded by confronting reality, not by deflecting it. Their progress was not the result of being exempted from accountability, but of embracing it.

To call for responsibility is not racism. To expect behavior to meet the requirements of law, school, health, and work is not White supremacy. It is civilization. The refusal to face this truth has cost Black America dearly. Until reflection replaces deflection, the phrase “disproportionately impacts” will remain not just a shield against accountability, but a guarantee of continued failure.

The numbers are not going away. The question is whether the excuses will.

This is where reflection replaces deflection.

Reading this is a start. Supporting it is the solution. If you're tired of the excuses and ready to stand for accountability, now is the time to step up.

Step Up: Become a Paid Subscriber: Support the work that tells uncomfortable truths.

Join the Core: Fund This Mission: Become a foundational partner in the fight for reality.

Make a One-Time Contribution: Fuel the work of accountability with a one-time gift.

Arm Someone With the Truth: Give a Gift Subscription: Don't just face the truth. Share it.

Thank you for stating the obvious that everyone is afraid to say. I have taught in all black schools where the kids were absolutely out of control and there were no consequences for bad behavior. Even if administrators tried the parents did not back up the school. Teachers are routinely threatened with violence by parents who do not like that their kid did absolutely nothing and so got a bad grade, or was violent and so was suspended. The old disciplinary system with punishments like detention are largely gone. When kids get suspended they treat it like a vacation. It’s not just two disruptive kids - it becomes the majority. Those who want to succeed usually succumb to peer pressure by around seventh or eighth grade and join the disruptive kids, even joining gangs. It is impossible to teach in these circumstances. Teachers are not just disrespected, we are abused. I taught SAT prep this summer to almost all kids of Indian origin. They were well behaved, motivated, respectful and an absolute delight. They did an incredible amount of homework and their parents were all in fur their education. They realized how fortunate they are to be in this country and how hard their parents worked to give them every advantage and opportunity. I could actually teach ! Even the Vietnamese kids I taught in very bad neighborhoods were hard working, respectful and smart. It’s culture but you can be cancelled or worse for saying it. Only the black community itself can solve this with a serious rethinking of values. Maybe as the welfare state gets dismantled this self reflection will become necessary. But politicians both white and black - and other - will continue to fan the flames of blame, giving us riots instead of employable citizens.

The title is a bit strange. Did you mean "Accept" rather than "except"?